Chapter 1

Don Paco’s Challenge to Experimental Sociology

“The professor is interested in how I built this house in Buenos Aires,” Don Paco Ubarri said, although I was trying very much not to look interested. “It is a story of triumph over adversity that must be taken down in the writings on his pad.” He repeated the word triunfo (triumph), the saliva in his mouth relishing the word’s Spanish pronunciation.

The Buenos Aires where Don Paco accomplished his triunfo was not the Buenos Aires of tangos and Evita Peron. It was the Buenos Aires of San Juan, Puerto Rico, the city’s largest slum, and it was built on the waters of the Martin Peña Channel, which connected the San José Lagoon to the sea through the Bay of San Juan. The name and place were linked only by the Puerto Rican penchant for naming something according to its opposite. Buenos Aires did not have buenos aires.

Centuries of human waste erupting from the sewers of San Juan had poured into the lagoon and into the channel. The waste was then carried by the tides into the bay and on to the sea. On its journey, the waste drifted down to the bottom of the waterway to form tar-like layers of sludge. When sheets of warm tropical rain swept in, the choked-up sewers emptying into the waterways combined with the tides and the wind to churn up the bottom sludge, leaving the air heavy with the stench of new and old excrement.

On that morning, after one of those downpours, I was trying to end an interview with Don Paco because of the ominously familiar rumblings in my stomach. Breathing slowly, so as not to inhale too much of the stench rising like fog from the dark waters, I tried to divert him.

“Don Paco, the story without doubt has great validity. But, with your permission, we should schedule it for another visit when I can stay longer and hear it fully.”

He would not be diverted.

“Please excuse me but it could be, puede ser, that much could be learned today if we could begin. I have been preparing all morning to tell the story of my life in Buenos Aires. I waited patiently for the professor to finish asking those questions he brought from the books in the university.”

Questions brought from the university! He insulted me but I kept quiet. Was he insinuating that the questions I had been asking him from my carefully constructed interviews were superficial or irrelevant? Just exactly what did he mean? After all, I was born and raised in Puerto Rico, spoke Spanish fluently, had a Puerto Rican mother and a large extended family in San Juan. I was as Puerto Rican as he was. Moreover, when I returned to Puerto Rico the previous year, 1957, I had just received a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Iowa at the age of 26, and this was after two years of military service and one year of loafing. In graduate school I was complimented for my mastery of research methods. On top of that, the questions Don Paco seemed to doubt were developed by an experienced research team at the University of Puerto Rico where I worked. Finally, no less a researcher than August B. Hollingshead, my collaborator from Yale University’s Department of Sociology, a world renowned sociologist, recently stated that Rogler had recruited and trained the best research team he had ever seen. Everyone knew that Hollingshead’s standards of excellence kept him from giving easy compliments. Don Paco, how can you doubt the quality of my questions!

Don Paco and I were face to face sitting on shoeshine boxes on the floor of the shack that was his home. The callused toes on his cracked, leathery feet had not been disciplined by shoes and they fanned out like the fingers on his hand. His face was coffee colored, the beard and mustache scruffy, and the corners of his mouth tilted slightly upward into a frozen half-smile, as if a paint job to make him a clown remained unfinished. His clothes were discards of other shack dwellers. The sludge-stained pants were rolled to his knees and the sleeves of his shirt were pushed up, signaling that he was on the verge of important work even though he had not been employed for several years. He supported his family with meager welfare payments supplemented by slim cuts from the occasional sale of clandestine rum made by a neighbor, ron cañita.

“The professor must understand that the story cannot be told in one visit. It has the quality of an epic,” Don Paco replied. Once again his command of words surprised me as did his majestic Spanish pronunciation.

His “j”s and “z”s were pronounced in prestigious Castilian Spanish, but it was not clear whether Don Paco’s unusual speech was an affectation or a speech defect. My guess would be an affectation since in previous interviews I had heard him address other persons, including his wife and two children, with the formal usted. He never used the familiar tu. All this seemed to reflect a self-concept of occupying a lofty place in the scheme of life.

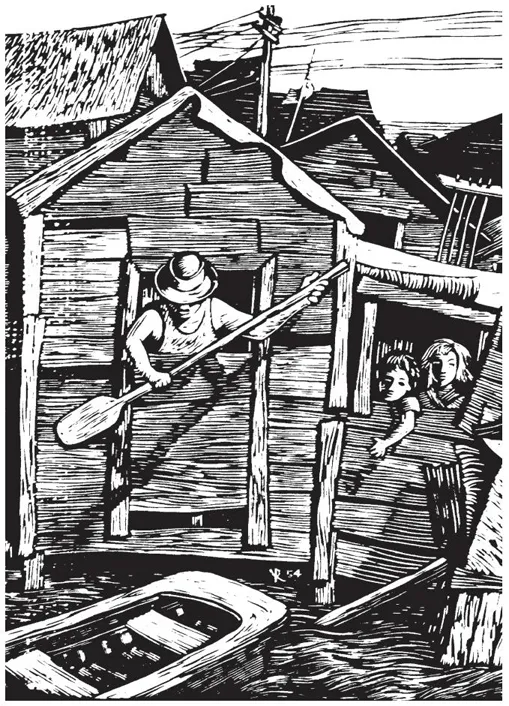

The floor of his shack was held up a few feet above the stirred-up waters by corner pilings. The pilings were buried in the sludge at the bottom of the channel. Moored to one of them was what appeared through the window to be a half-submerged boat—with a mysterious hump on the stern—floating and swaying completely unperturbed. The window was an opening where a strip of corrugated zinc somehow had been left off. A moment would pass then the infernal noise of thump, thump, thump as the boat bumped into the piling. This would shake the shack already trembling from the outgoing tide. Once when the thump was delayed for a moment I looked out the window hoping to see the boat drifting away with the tide. No such luck. It was securely fastened. No wonder my research assistants had complained of seasickness when they interviewed Don Paco’s wife.

“Don Paco, it pains me to tell you but I am late for an appointment at the University of Puerto Rico, a profesor americano. He just arrived from the United States,” I said, looking at my watch with phony urgency. The appointment was a lie. “When americanos schedule an appointment, they don’t mean mas o menos,” I said, playing on the lie.

“The professor could tell the profesor americano my story to explain being late for the appointment,” he said, taking surprising liberties with my honest attempt to lie.

At that moment it was imperative that I leave. The vague discomfort inside my stomach that I hoped was my body’s reaction to the stench of Buenos Aires moved to a gut at the bottom of my lower abdomen. The gut coiled and lunged. The painful spasm made the pencil in my trembling hand appear far away and it left my scribbling more unreadable than usual. Apparently the medications I had begun to take for tropical sprue were not working.

I braced myself for the next spasm. Pretending to stretch, I stood up from the shoeshine box and tried to tighten my buttocks while relaxing my stomach. It did not work. The spasm squirted the detestable diarrhea. It seeped through my underpants and began running down my legs. To keep it from spreading I sat down. Maybe the stench of Buenos Aires would cloak the stench coming from me. Don Paco, who appeared oblivious to all of this, would think that the sewers of San Juan were guilty, not me. I wanted to back out of the door and get the hell out of Buenos Aires.

The predicament had an even sharper edge because I did not believe in the kind of research I was doing in Buenos Aires. I had agreed to direct the research only because collaboration with the renowned Professor Hollingshead would advance my academic career, and I was determined to do the research competently. But my conviction remained unchanged: A scientific sociology could not be developed by relying on interviews such as those with Don Paco. Interviews were too flimsy an instrument to build the foundations of a science. The appropriate procedure for sociologists was to select subjects carefully, usually students from undergraduate classes, and then isolate them in a room called a laboratory. That way outside influences would not interfere. The subjects would be asked to perform certain tasks that had already been planned. Oneway mirrors would enable the researcher to look into the laboratories at the subjects and record their behavior accurately with tape recorders and cameras. In sociology, this was called a small-group laboratory. The main purpose was to gather clues about the most “basic social processes,” which meant how persons form groups and how groups influence persons. The whole procedure was called experimental sociology. To me, experimental sociology was necessary to the development of a scientific sociology. At that moment, however, I was sitting on a shoeshine box in a shack in a misnamed, odiferous slum on top of the Martin Peña sewer, trying to obey research proprieties and the customs of Puerto Rican politeness while carrying a load of liquid shit in my pants.

Don Paco, however, was as oblivious to my convictions about experimental sociology as he was to my gastrointestinal problem. He was determined to tell his story in his regal Castilian.

“The professor can see that all the dry shoreline in Buenos Aires is crowded with families,” he began, pointing to the shoreline, convinced of my abiding interest in slum development. “That meant that I had to build further out deep into the channel. And that meant that I had to get pilings. I had to bribe a night watchman at one of those construction sites in Hato Rey where the big American banks are being built.”

“The pilings look heavy. How did you get them here?” I asked.

“Heavier than the cross of Christ and the devil’s forked tail put together! I tied them together and pulled them across the channel with my boat,” he said, gesturing toward the mysterious boat that was still thumping against one of the pilings. “And with the help of my friends, who were building their own homes, I pounded the pilings into the bottom sludge deep enough to make them secure.”

“Secure?” I asked, unintentionally.

“Yes, secure,” he answered.

Maybe secure from his viewpoint, but not from mine, I said to myself, as the boat’s continued thumping against the piling shook the shack, which shook my disturbed stomach.

Don Paco described how he nailed a patchwork of discarded plywood on the pilings to serve as the floor of his emerging home. Some of the plywood patches advertised political figures, in particular, candidates for the Popular Democratic Party. The patch under the shoeshine boxes we were sitting on, however, simply stated Tome Cerveza...