![]()

1

Introduction

Background

In preparing to write the first edition of this book back in 2003, I attended a number of multi-cultural sessions at NCTM conferences. In one of the sessions, Jean, a Navaho teacher of Navaho students from a reservation school, presented the general characteristics of her students as well as the math curriculum offered at the school. (The names of all teachers in this chapter are fictitious.) Although Jean commented that the school was sensitive to the culture of the students, I noticed that it was directed toward behavioral do’s and don’ts, such as the following: “The teacher should not expect eye contact from students before students become comfortable with the teacher.”

Thinking that the case of teacher and students sharing the same cultural heritage might have some beneficial effects on classroom interactions or pedagogy, I asked: “Given that you share the culture of your students, are there methods or strategies that you use with your students that you might not use with, say, Asian or African students?” I thought it was an innocent question until Jean snapped back: “I don’t teach my students any differently than I would any other students!” I immediately realized that Jean may have interpreted the question as a negative cultural comment: “Do you dumb down your curriculum for these poor Indians?” Thinking that it would take more than a clarification of the question to get my meaning across to Jean, I kept quiet and made a mental note: “Be careful of your questions because some may trigger assumed racist implications.”

The difficulty of writing a book on multicultural classroom interactions became clearer to me as I stopped random groups of participants at the conferences and asked questions like: “Do you think the NCTM [National Council of Teachers of Mathematics] Standards really work for all students? Do they work for your students?” To those questions, Mary, one in a group of three African American women teaching African American students, replied: “Some of the approaches don’t work for our students. Take collaborative learning, for example. It is ineffective for groups of more than two of our students. Larger groups result in a waste of time. They don’t come to us knowing how to work in groups.” I mentioned her comment to two African American males, Ben and Dante. Dante immediately said, “That is not true! Our students can work in groups. They may, however, have to be taught how. Beginning with groups of two and then extending to larger groups will help them work productively in groups of four.” He then cited research showing how cooperative groups increased achievement of African Americans. His tone and inflection caught my attention more than his words. “I noticed,” I said to him, “that you sounded offended by Mary’s comment.” He laughed at the insight and agreed. I continued: “Should I not write this book or ask such questions? My goal is not to offend people. Can I hope to make any difference, or will I just be viewed as a narrow-minded racist?” Ben replied, “Yes, they are sensitive, but they are also good questions demanding thoughtful and difficult responses. Educators need to discuss them openly, just as we are doing now. Go for it!”

And so I did. For the first edition, I invited Katherine Owens as coauthor for two reasons: First, Kathie had impressed me with insights on Standards-based mathematics through her submission of a profile for one of my other books now in its second edition (Germain-McCarthy, 2014). Second, I needed help wrestling with whatever issues might come up with the topic, and I thought Kathie’s Euro-American background would provide alternative perspectives for discussions. For this second edition, I updated Kathie’s profiles.

Purpose of This Book

Multiculturalism is a concept that includes attention to perspectives on issues regarding gender, age, religion, class, sexual orientation, and variations in abilities. I have chosen to focus this book on the teaching of and learning by students from different ethnicities. Since the first edition, much has been researched and written about multicultural issues. This edition has updates on the literature and how it is reflected in the teaching of the teachers profiled in this book.

This is a book for anyone interested in gaining insight on how the reform movement in mathematics, as advocated by NCTM, is being effectively implemented with diverse students. My intention is not to present unique lessons but to show how NCTM Standards-based strategies, now embodied in the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics, are being implemented in the classroom. The lessons depict the teachers’ and students’ actions that unite the goals of multicultural education with the mathematics curriculum. The teacher profiles that constitute the heart of the book are descriptions constructed from classroom visits, written statements, interviews, or videotapes of how teachers implement Standards-based lessons in their classrooms. The book highlights the profiles of teachers across the nation who have gone beyond mere awareness of reform recommendations in mathematics to conceptualizing and implementing new curricula for students of diverse students. It shows how teachers implement effective classroom instruction recommended by research and how their students respond.

Teachers and teacher educators (in-service and pre-service), mathematics professors, and curriculum supervisors and superintendents in charge of instruction will find the book of interest and useful because it provides some answers to a question many pre-service students and teachers ask: “Where are the real teachers who are effectively doing this stuff, and how are they doing it?”

The Sensitive Questions

Readers will also find the book useful as a fertile ground for launching discussions centered on multicultural issues in education. I believe that sensitive questions will arise as readers reflect on the approaches used by the teachers profiled. It is difficult to anticipate all of these questions because we all have lenses tinted by our personal experiences through which we view and interpret the world—as my experience with the Navaho teacher demonstrated. Readers are encouraged to read the profiles and to avoid making quick generalizations about any group because no ethnic group is homogeneous; people of the same ethnicity may differ in their history, culture, and language. I, for example, am a naturalized American and maybe classified as Black, African American or “other” since I am of mixed race; yet my ethnic identity is more specific than that because I was raised in a Haitian culture where I spoke only French and Creole at home and would thus classify myself as Haitian American.

I have taken care to present an overview of the students and the school’s community so that the profiles may be read as representing one example of how one teacher, teaching students within an ethnic group having these particular characteristics, successfully challenges those students to think about and do important mathematics. To help eliminate stereotyping of any group, it is important to keep in mind that each profile was selected as one instructional example among many variations. Finally, I apologize in advance for using any name that may be offensive to some groups. The literature provides little help in selecting acceptable descriptors since I found a number of different names used to identify the same or related groups. Even within the same work I see: First Nation People versus Native American versus People from Indigenous Nations; White versus Euro-American; Black versus African American; Latino/a versus Latina/o versus Latino versus Hispanic; People of color versus minorities; traditionally underserved group versus marginalized group versus underserved students versus students of color and low socioeconomic students; linguistically and cultural diverse learner (LCDL) versus English as a second language learners (ESL) versus English language learners (ELL) versus limited English proficiency (LEP) versus English for speakers of other languages (ESOL). I have decided to use the name given for each group based on the name used by the author whose work I cite.

Chapter Overviews

Chapter 2 presents overviews of the NCTM and Common Core Standards for Mathematics (CCSM) documents and some of the research that provided the rationale for their constructivistic framework. Chapter 3 describes key elements of exemplary practices in mathematics education. Chapter 4 presents definitions of and research on multicultural education. Chapters 5 through 11 are profiles of teachers who are successfully implementing the NCTM Standards with classes that include ethnic diversity. The chapters also include a Discussion with Colleagues section where ideas from the profile are clarified or expanded; a Commentary section that highlights the specific standards, issues, or research that informed the strategies the teachers used; and a lesson or Unit Overview in a lesson plan format that summarizes key ideas for implementing the lesson or unit, along with the specific NCTM and CCSSM standard, principles, and practices they address. While the profiles incorporate a number of different content standards, they all reflect the NCTM principles for access and equity, curriculum, teaching and learning, and assessment, as well as the processes for problem solving, reasoning, connection, and communication. Although the unit overviews specify grade levels or a particular ethnic group, readers will find that they can be easily modified to fit the needs of different levels or types of students. Ideas for extensions of the curricula will emerge not only because of the richness of the activities but also because the lessons move from the concrete to the abstract. Finally, the last chapter discusses what the education community and policy makers need to consider in order to create a safe environment to discuss and promote equitable practices in our schools.

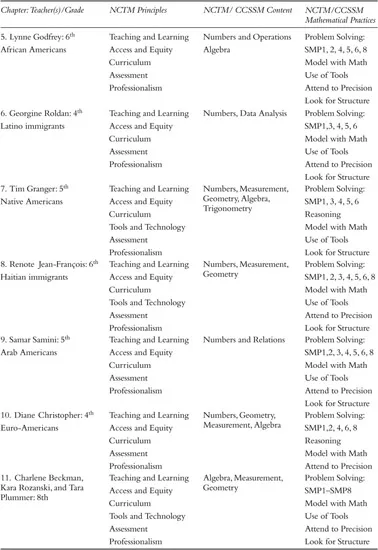

The profiles presented in this book show that multicultural education is a vision of what education can be, should be, and must be for all students. Figure 1.1 summarizes the ethnic group and the NCTM and CCSSM principles and standards addressed in each profile.

Figure 1.1 Principles, Standards, and Practices in the Profiles

![]()

2

Trends and Issues Leading to Standards-Based Reform

Twenty-fi ve years ago NCTM released Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for Teaching Mathematics, which presented a comprehensive vision for mathematics teaching, learning, and assessment in grades K–12. Other significant publications, including Principles and Standards for School Mathematics and the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics continue to identify what we believe students should know and be able to do throughout their school mathematics experience.

Linda Gojak, past president, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2014)

In the preceding quote from Linda Gojak’s NCTM 2014 final President’s Message (2014), she summarizes the major Standards-based documents that seek to guide teaching and learning for the 21st century. To better understand the shifts required for their implementation, a brief background on the major theories and documents that underlie these documents, which I will call Standards-based, are provided next.

Constructivism

Because constructivism is applied or experienced in an environment where learners are trying to make sense of a problematic situation by constructing their own knowledge about the world around them, it is a framework for the Standards-based documents since they advocate for conceptual understanding as a major focus for teaching and learning. Jean Piaget (1973) wrote:

To understand is to discover… [A] student who achieves a certain knowledge through free investigation and spontaneous effort will later be able to retain it: he will have acquired a methodology that can serve him for the rest of his life, which will stimulate his curiosity without the risk of exhausting it. At the very least, instead of his having his memory take priority over his reasoning power… he will learn to make his reason function by himself and will build his ideas freely. The goal of intellectual education is not to know how to repeat or retain ready-made truths. It is in learning to master the truth by oneself at the risk of losing a lot of time and of going through all the roundabout ways that are inherent in real activity.

(106)

Thus, learning is not simply the acquisition of information and skills; it also includes the acquisition of a deep understanding. Simon (1995) notes that constructivism does not define a specific way to teach mathematics. Rather, it “describes knowledge development whether or not there is a teacher present or teaching is going on” (17). Some constructivists view the small group process—by which students work together on mathematical tasks that require a high level of communication about a problem—a crucial component of the development of conceptual understanding. Social interaction, as an essential factor in a learner’s organization of experiences, underlies the theory of social constructivism. According to Vygotsky (1978), “Any function in the child’s cultural development appears twice on two planes. First it appears on the social plane, and then on the psychological plane” (57). Thus, the constructivist approach begins with what the students already believe regarding a particular idea; students’ attempts to verify these ideas then serv...