![]()

1

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Ariadne’s Thread:

Grotowski’s journey through the theatre

Lisa Wolford

The long and multifaceted creative journey of stage director and performance researcher Jerzy Grotowski stands out as one of the most original and eccentric careers in the annals of theatre history. Beginning his professional work in 1959 as artistic director of a sparsely subsidized theatre in the small Polish city of Opole, Grotowski rose to international prominence within ten years, and was hailed as one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century theatre.1 An early pioneer in the field of environmental theatre, Grotowski’s contributions to contemporary performance include a reconceptualization of the physical basis of the actor’s art and an emphasis on the performer’s obligation to daily training, as well as the exploration and refinement of a performance technique rooted in the principles of Stanislavsky’s Method of Physical Actions.2 The group Grotowski founded, the Teatr Laboratorium, developed in a distinctive performance style that emphasized the encounter between actor and spectator as the core of the theatrical exchange, stripping away extraneous elements of costume and scenery in order to focus on the actor’s ability to create transformation by means of her/his art alone (Grotowski 1968).

Grotowski rejected the notion of theatre as entertainment, seeking instead to revitalize the ritualistic function of performance as a site of communion (with others, with transcendent forces), a function he attributes to the ritual performance traditions of tribal cultures and to the archaic roots of Western theatre (see Kumiega 1985:128-143). Drawing on the sacred images of Catholicism, as well as on Jung’s theory of archetypes and Durkheim’s cross-cultural study of religious behaviors (see Ch. 2, this volume), Grotowski’s productions sought to challenge the audience by confronting the central myths of Polish culture, provoking spectators into a re-evaluation of their most deeply held beliefs. The productions of the Laboratory Theatre were characterized by a transgressive and at times blasphemous treatment of sacred

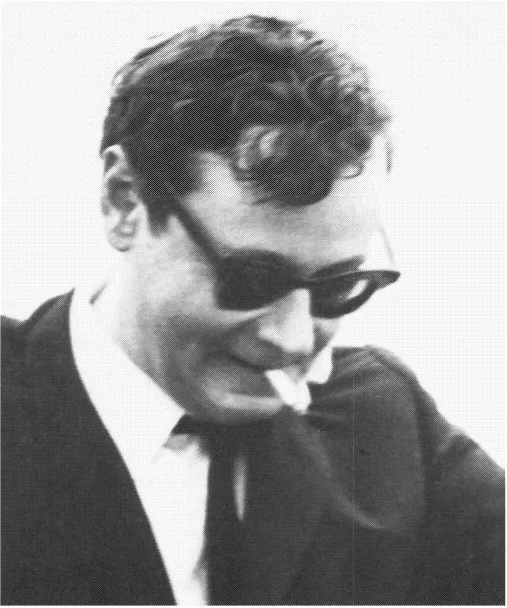

Plate 1.1 Jerzy Grotowski in the late 1960s. (Photo: Nordisk Teaterlaboratorium.)

cultural symbols. Grotowski realized that identification with myth was impossible in an era no longer united by a "‘common sky’ of belief’ and that confrontation with myth was the only means to penetrate beyond superficial acceptance of religious beliefs; by means of such confrontation he invited the individual (both actor and spectator) to explore his or her own sense of truth in light of the values encoded in the myth (see Ch. 2). Grotowski’s productions were ritualistic, not in the exoticized or Orientalist sense of imitating or appropriating elements from the rituals of other cultures, but rather in terms of their reliance on Christian themes and imagery, a consistent focus on martyrdom as a heroic act, and an emphasis on music, chant and poetry rather than naturalistic speech.

One element of Grotowski’s work that remained consistent from the beginning was his emphasis on sustained and methodical research involving the fundamental principles of the actor’s art. In Towards a Poor Theatre, Grotowski articulates the need for a type of performance laboratory modeled after the Bohr Institute (1968:127-31), a forum for investigation of the principles governing artistic creativity. While he rejects any possibility of discovering "recipes" or formulae for creation, which he asserts would inevitably be sterile, Grotowski voices a desire to demystify the creative process, seeking to define a methodology of performance training that would free the actor to accomplish his or her work without obstruction and also without waiting for random inspiration. This notion that the actor’s craft, while by no means scientific, is governed by certain "objective laws" (Grotowski 1968:128) foreshadows later developments in Grotowski’s lifework.a

In 1970, when he was thirty-seven years old, Grotowski startled the international theatre community by announcing that he no longer intended to develop new productions, having arrived at the conclusion that it was impossible for theatre to facilitate the type of communion between actor and spectator that he sought to realize within the frame of performance (see Kumiega 1985:144-156). "My work as a director, in the classical sense, was something beautiful. But a certain automatism had begun to encroach. What are you doing? Othello. And after? After, I. . . . One can become mechanical" (Thibaudat 1989:35). Rather than repeating his prior achievements, Grotowski preferred to shift his professional activity toward hitherto unexplored areas at the intersection of performance, anthropology, and ritual studies.

Robert Findlay estimates that the world-wide bibliography on Grotowski stands at approximately 20,000 entries (in Wolford 1996a:xv). Limitations of length for this volume make it unfeasible even to include all the texts on Grotowski’s work originally published in The Drama Review, despite the fact that the journal played a fundamental role in introducing Grotowski’s work to Western audiences. Richard Schechner and I have tried to make a representative selection of texts from each of the recognized periods of Grotowski’s research, though our collection undeniably privileges English-language materials and previously translated articles. In addition to the predictable abundance of Polish documents, significant works continue to appear in French, Italian, and Mexican books and journals, as well as in Middle Eastern, Asian, and Russian publications.

The record this volume presents is incomplete from another perspective as well. The question of what gets recorded and whose voice is authorized to speak becomes particularly complex in relation to writings detailing the work of Grotowski’s post-theatrical period. Both Theatre of Participation and Theatre of Sources have been documented almost exclusively by occasional or outside participants; long-term practitioners and workleaders in these projects have tended to be silent about the precise details of the activities with which they were involved. Seen from the vantage of the practitioner, it is easy to understand how premature translation of nonverbal processes can threaten the life of a creative work (particularly one premised on disruption of the internal discursive voice), as the practitioner then falls prey to the temptation to reduce the new experience to the category of what is already known, imposing familiar formulas that fit badly or not at all. But from the viewpoint of scholarship, of performance history, the scarcity of documentation from the work of the paratheatrical and Theatre of Sources periods of Grotowski’s research presents enormous complexities. Most available accounts of activities conducted in these years are written by persons who arrived for brief and at times relatively unstructured periods of work. Such documents can be extremely valuable, especially when inflected with the conscious artistry of a skilled writer such as Jennifer Kumiega or the embedded theory of an anthropologist as knowledgeable of ritual practice as Ronald Grimes. But the silence of those who were systematically present, working day after day for a number of years, makes it easy for the reader to overlook the fact that there is other knowledge to which we simply do not have access. A substantial portion of the paratheatrical work in fact involved no outside participants, but was conducted under closed conditions with a small team of skilled practitioners. The fact that none of these people have documented their experience creates a skewed image, emphasizing the more loosely structured, large-group experiments over the focused work of the resident team. The people who know aren’t talking – at least not openly, at least not now, and possibly not ever. And so the rest of the story, which reveals a great deal about the question of conscious structure in works that highlighted spontaneity, about strategies deployed by the leaders in participatory work, about the intensive preparation conducted behind closed doors – all this remains unwritten.

OUT OF THE LABYRINTH

Performance theorists who examine the development of Grotowski’s research emphasize the implications and significance of his decision at the initiation of the paratheatrical phase of his activity to abandon the formal structure of theatre production, eliminating the distinction between actors and spectators. Bonnie Marranca, with a discernible note of political ambivalence, comments on Grotowski’s "distaste for theatre as representation" and suggests that his post-theatrical work provides "the most extreme example of the contemporary urge to turn away from spectacle, spectatorship, and by extension, aesthetics" (in Marranca and Dasgupta 1991:16). Even Eugenio Barba, who has always been among Grotowski’s most steadfast and visible supporters and who began his own theatrical career assisting Grotowski in Opole during the poor theatre phase of Grotowski’s work, finds himself at a loss when attempting to categorize the Polish researcher’s work in the field of Art as vehicle. "I have been told that this is not a performance," wrote Barba in response to a rare public session held at Grotowski’s Pontedera Workcenter in 1990, "yet I see ‘people who are acting.’ If what is happening here is only for them, then why am I here? Why was I invited and why did I come?" (1995:99)

The question of how to situate Grotowski’s post-theatrical research remains contested, at times explosively so. Although he did not premiere any new productions after 1968, Grotowski remained active in a multi-faceted role as creative artist, performance theorist, artistic teacher, and pioneer of innovative performance genres. Figures as diverse as Jan Kott, Robert Brustein, and Charles Marowitz have questioned the validity of his post-theatrical work on the grounds that it offers little that can be put to practical use in more conventional forms of theatre practice. Such criticism reflects a common, almost pervasive thread of negative response to Grotowski’s post-theatrical activity, focusing on the dubious legitimacy of work that utilizes artistic means but is not mounted for public view. How is the value of such work to be judged if it is not assessed by spectators and critics? What and whom does it serve, if its primary purpose is not to communicate with an audience? What is the use of the actor’s talent if the work does not culminate in a publicly accessible production?

Indeed, despite Grotowski’s division of his work into five separate phases, from an outside perspective the relevant distinction appears to boil down to only two: his work in the theatre, which received an enormous amount of international recognition, and the work he began after "leaving theatre behind," which has been perceived as becoming progressively more isolated and obscure. People of the theatre have tended, by and large, to (mis)interpret the post-theatrical phase(s) of Grotowski’s work as somewhat suspect, self-indulgent, and elitist, having more to do with therapy or alternative spiritualities than with art. Kazimierz Braun, as summarized by Filipowicz, depicts Grotowski as "a has-been who left no trace in the collective cultural memory or the current theatre practice," (Ch. 40:402) while Marowitz suggests that "As an ‘influence,’ Grotowski’s dynamic corporeality came and went within a period of about ten years" (Ch. 34:351). The possibility that Grotowski’s post-theatrical research might have value in itself, quite apart from the question of its usefulness for theatre (or in most evaluations, its lack thereof), has received serious consideration only from a small circle of respected European theatrologues and an even smaller group of American scholars.

Grotowski himself found nothing shocking or self-contradictory in the unusual course of his creative journey:

In appearance, and for some people in a scandalous or incomprehensible manner, I passed through very contradictory periods; but in truth [...] the line is quite direct. I have always sought to prolong the investigation, but when one arrives at a certain point, in order to take a step forward, one must enlarge the field. The emphases shift. [. . .] Some historians speak of cuts in my itinerary, but I have more the impression of a thread which I have followed, like Ariadne’s thread in the labyrinth, one sole thread. And I am still catching clusters of interests that I had also before doing theatre, as if everything must rejoin.

(Thibaudat 1995:29)

Grotowski saw the various phases of his work as being unified by certain consistent desires and questions, underlying interests that fascinated him since childhood, long before he ever thought of pursuing work in the field of theatre. Indeed, Grotowski claimed that it was almost by chance that he chose a career in theatre at all. When the time arrived for him to enroll for university studies, he considered three different fields which he thought offered more or less equal opportunities to pursue his primary interests: theatre, Sanskrit studies, and psychology. The entrance examination for the theatre school was scheduled first among the three, and when Grotowski (contrary to his own expectations), was accepted into the theatre program he chose to enroll.3 Grotowski suggested that the underlying impulses of his work would have remained much the same even if he had chosen to pursue a career in another field.

Writing to Grotowski in the form of a published letter, Barba meditates on the enormous separation between his own work and that of his first teacher:

You once said that you were like Aramis, who, when he was a musketeer always talked about becoming a monk, and when he then began his religious career always talked about his life as a soldier. Nowadays you often analyze your productions of twenty and thirty years ago. For a long time, you haven’t wanted to make any more productions. Those who have seen your work know that you could make marvelous ones.

You, however, are weaving other threads. You have fulfilled – you say - the task which was entrusted to you. [. . .]

You often explained your choice. But you owe us no explanation. You ask new questions. Do you still ask my questions? [. . .]

What did we believe in so many years ago, when you were weaving your productions and I imagined that I was learning about theatre and, instead, was discovering myself while discovering you? You probably already believed in what you believe in today.

Is there, then, something which is steadfast and absolute? If so, it is found in the depths of a labyrinth. The thread thus becomes sacred because it does not bind us but connects us to someone or to something which keeps us alive.

(Barba 1995:136)

Barba’s imagery of weaving and threads resonates strongly with Grotowski’s own evocation of his lifework as being unified by "one sole thread." I suspect that Grotowski would have answered the question of belief which Barba raises in the affirmative – saying that yes, when he worked as a stage director, he already believed in much of what he believed in during the period when his life and work were drawing to a close.

The thread that leads out of the labyrinth, Ariadne’s golden skein, marks the trace of an unbroken journey toward elsewhere.

THE MANIFESTATIONS OF PROTEUS

In his most celebrated manifestation, Grotowski was a stage director, founder of the Theatre of 13 Rows in Opole, Poland. This coincides with the "Theatre of Productions" or first period of Grotowski’s work, which Zbigniew Osinski dates from 1959-1969. It is the Grotowski of this manifestation that Findlay describes as "[having] done more than anyone else to bring about a re-evaluation of the theatre and the premises upon which theatre has stood, not simply in the twentieth century, but for all time" (in Osinski 1986:9). Considering the impact of the Laboratory Theatre’s work on performance theory and presentational styles, it is startling to remember that the ensemble mounted new productions for only ten years of its history, and was the object of critical attention for only half that time.

Even during the explicitly theatrical phase of his work, Grotowski problematized the relation between pretense and performance, leading his actors toward the accomplishment of a "total act," an absolute disarmament by means of which the actor "reveals [...] and sacrifices the innermost part of himself [. . .] that which is not intended for the eyes of the world" (Grotowski 1968:35). Actors in the Laboratory Theatre were not concerned with questions of character or with placing themselves in the given circumstances of a fictional role. Rather, their task was to construct a form of testimony drawing on deeply meaningful and secret experiences from their own lives, articulated in such a way that this act of revelation could serve as a provocation for the spectator. As Philip Auslander notes, "Grotowski privileges the self over the role in that the role is primarily a tool for self-exposure" (1995:64).

In Towards a Poor Theatre, Grotowski cited the "relationship of perceptual, direct, ‘live’ communion" between actor and spectator as the core element of the theatrical exchange. "At least one spectator is needed to make it a performance. [. . .] We can thus define the theatre as ‘what takes place between spectator and actor’" (1968:32). According to Kumiega,

Grotowski believed that the actor’s gift of self-sacrifice had the potential to realize some of the fundamental aspects of ritual, for which he was searching in the theatrical experience: i.e. an act of revelation and communion between those present which would consequently permit deeper knowledge and experience of self and others (and hence change).

(1985:143)

Underlying Grotowski’s work during this period was a conviction regarding the capacities of performance to catalyse inner transformational processes, a function he linked to archaic performative forms, historically prior (in Western culture, at any rate) to the division between sacred and aesthetic aspects of art. Grotowski sought to reclaim and revitalize this affective capacity of performance, yet with full awareness that identification with conventional religious forms could no longer serve to invoke profound change on individual or communal levels in a world which lacked a "common sky" of belief.

From the earliest phases of his research, throughout each of his various forms and manifestations, Grotowski’s investigations have been motivated by certain elusive but strangely consistent desires: a longing for communion and for the possibility of lasting transformation of the actor/doer as human being. Ludwik Flaszen describes the underlying goal of Laboratory Theatre performances using a rhetoric that is strangely resonant with that adopted by Grotowski in later phases of work:

Grotowski’s productions aim to bring back a Utopia of those elementary experiences provoked by collective ritual, in which the community dreamed ecstatically of its own essence, of its place in a total, undifferentiated reality, where Beauty did not differ from Truth, emotion from intellect, spirit from body, joy from pain; where the individual seemed to feel a connection with the Whole of Being.

(Flaszen in Kumiega 1985:156)

At a certain point in his research, Growtowski discovered that the conventional structure of performance could neither foster nor contain the type of communion he hoped to create. Kumiega suggests that the impossibility of systematically educating the spectator and the passivity of his or her conventionally assigned role were factors that obstructed the possibility for authentic encounter within a theatrical context (1985:150). "If Grotowski was really searching for the same level of authenticity as could be experienced in archaic pre-th...