eBook - ePub

Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades

Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule

Adrian J. Boas

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 288 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades

Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule

Adrian J. Boas

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Adrian Boas's combined use of historical and archaeological evidence together with first-hand accounts written by visiting pilgrims results in a multi-faceted perspective on Crusader Jerusalem.

Generously illustrated, this book will serve both as a scholarly account of this city's archaeology and history, and a useful guide for the interested reader to a city at the centre of international and religious interest and conflict today.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades di Adrian J. Boas in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Ciencias sociales e Arqueología. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

PART I

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

In appearance, the Old City of Jerusalem is still essentially a medieval city. However, within the confines of its walls some fundamental changes have taken place since the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The gates are not locked at night and the walls no longer serve as bulwarks against a hostile outer world. The open fields around the inside of the walls, once used as fruit and vegetable gardens and open markets, have largely been overrun by construction works of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There is now electricity, gas, piped water and a reasonably modern sewage system. Nonetheless, with the exception of the Jewish Quarter, which has been largely rebuilt since 1967, the city is very much as it appeared nine hundred years ago and a visitor from the twelfth century would probably not have too much trouble in finding his way about.

Medieval Jerusalem (see the map on page) was the holiest of Christian cities, containing, as it still does, a multitude of pilgrimage sites. Like other cities where tourism and pilgrimage are staple industries, the city’s population can be divided into two distinct groups – permanent residents and visitors. In such cities the ratio between these two groups reflects the degree of success in ministering to the needs of visitors. A higher proportion of visitors to residents will be found in a city which is doing a better job at ‘selling itself’ to the public. Because of its spiritual attractions Jerusalem has always done this fairly well. The Middle Ages were no exception and, while we have no statistics, or at least none that are reliable, there can be little doubt that by such standards medieval Jerusalem was quite successful.

How can we judge the degree of success of a city which, to all intents and purposes, ceased to exist eight hundred years ago? One way to do this is to look at its surviving monuments. A large number of medieval public buildings can still be found in the city. In less than ninety years the Franks not only replaced all the churches destroyed under Muslim rule but built a large number of new ones, re-identifying and on occasion inventing holy sites to go with them. They also strengthened the fortifications and built a new palace, constructed monasteries, hospices, hospitals, covered market streets, bathhouses and various other institutions. The extent of Frankish efforts in the construction of these works has no parallel in the history of the city since the Byzantine period and by such standards Crusader Jerusalem seems to have been a great success as a pilgrimage city.

CHAPTER ONE

THE PHYSICAL SETTING

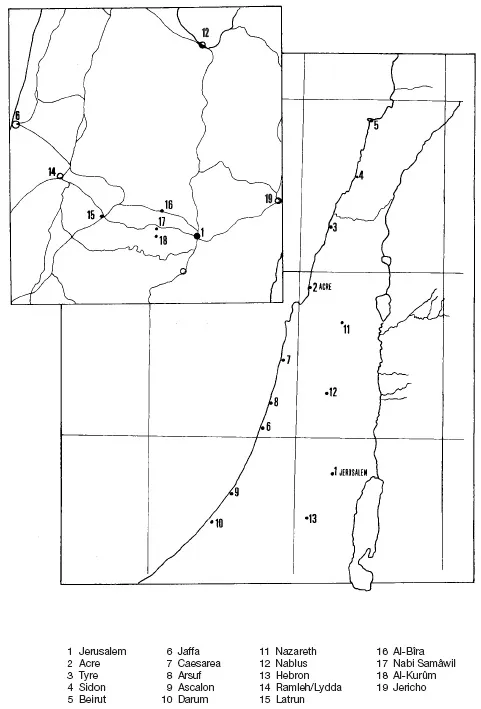

Jerusalem is situated on the watershed of the Judaean mountains, about 750 to 820 m above sea level (Figure 1.1). It is 58 km inland from the Mediterranean coast and 25 km west of the northern tip of the Dead Sea. Since it is positioned on what could hardly be considered an important commercial route south from Damascus via Nablus and a number of lesser roads, to Hebron in the south, Jericho and Amman in the east and Ramleh and Jaffa to the west, commerce has never really been a significant factor in its history. While it holds a certain role as a regional centre, Jerusalem has always owed its importance to religion and politics.

The present-day Old City, enclosed within its sixteenth-century walls, covers the same area, give or take a few square metres, as Crusader Jerusalem. It is located between two valleys, the Kidron to the east and the Hinnom to the west, which converge in the south at the site of the city’s principal natural water source, the Siloam Spring. Within this physical frame, the secondary Tyropoeon Valley, running through the city from north to south, divides it into two hills; Mount Zion to the west and Mount Moriah (the Temple Mount) to the east. The Siloam Spring is the only natural water source, a factor which would have limited the development of the city but was resolved by artificial solutions such as the construction of aqueducts, open reservoirs and cisterns.1

Jerusalem is located in an area of limestone and chalk and these serve as its principal building materials. They include the soft, pinkish post-tertiary limestone, of poor quality for building, locally known as Nari and the harder Hippurite limestone termed Mizzi.2 A white limestone known as Meleke (‘royal’) is also popular in building, as it is very easy to cut when freshly quarried but hardens when exposed. Crusader masons favoured two types of stone, the Mizzi for marginally drafted ashlars or roughly shaped fieldstones used in wall construction, and the softer Meleke for the finer, carefully drafted building stones with the distinctive Frankish diagonal tooling used for door and window frames and other architectural features.3

In the Crusader period the hills immediately around the city were devoid of trees suitable for timber. Sieges, droughts and the types of soil and rock in the region were not favourable to the establishment of natural forests. The Roman siege of the first century AD had depleted the forests and, long before the twelfth century, Arculfus (c. 670) had noted the need to transport firewood to Jerusalem from a small pine forest located slightly north of Hebron.4 It is unlikely that there was any improvement in this condition between the seventh century and the time when the Crusaders appeared on the scene.5 Indeed, by that time the situation must have worsened. If the forest near Hebron had survived that long, it may well have been denuded in 1098 during the Fatimid siege of Seljuk Jerusalem and perhaps again prior to the arrival of the Crusaders, when the Fatimids probably cut down any remaining trees in the region to provide themselves with wood in preparation for the approaching siege.6 The Franks would have depleted any remaining resources in their search for wood to construct their siege machinery.7 Throughout the Crusade period and later the lack of wood for firewood or construction remained a problem. Thus Theoderich (c. 1169) writes: ‘Wood suitable for building or for fires is dear there, because the Mount Lebanus – the only mountain which abounds in cedar, cypress, and pine-wood – is a long way off from them, and they cannot approach it for fear of the attacks of the infidels.’8 Later, in the fifteenth century, the pilgrim Felix Fabri refers to the difficulty of obtaining firewood for use in private kitchens.9

Figure 1.1 The Kingdom of Jerusalem (drawn by Dalit Weinblatt).

The vicinity of Crusader Jerusalem was an area of fairly intensive rural settlement.10 In addition to the larger towns and villages, like Bethlehem to the south and al-Bira (Magna Mahumeria) to the north, there were a number of smaller villages, farms and rural estate centres such as ar-Ram and al-Jib, al-Kurûm and Montjoie (Nabi Samâwil) to the north, al-Qubaiba (Parva Mahumeria), Motza (Colonia), Khirbet Mizza, Lifta (Clepsta), Khirbet Lowza and Aqua Bella to the west, and Bethpage and Bethany to the east. Monasteries were located at Ain Karem (St John in the Wood), Abu Ghosh (Emmaus/Fontenoid), Bethany and Nabi Samâwil (Montjoie). Many of these rural properties were possessions of property owners resident in the city. Occasionally these were private individuals, but more often they were the king, the churches and military orders. Most of the settlements supplied the city with farm produce, livestock, poultry, cereals, fruit and vegetables and processed products such as cheese, wine and oil.11 Some no doubt provided the city with pottery and other manufactured items.

CHAPTER TWO

BACKGROUND TO THE CRUSADER PERIOD

As noted earlier, the Frankish conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, with the ensuing slaughter and the banishment of the surviving population, left the city almost devoid of inhabitants. However, within a few decades the city was repopulated and for most of the twelfth century it thrived as the administrative capital and as the focus of a massive pilgrimage movement. Under the Franks Jerusalem became more cosmopolitan in character than it had been under Muslim rule. Buildings in the Romanesque style rose among the local Eastern architecture. Pilgrims from every Christian country visited the city, mixing in the streets with the Eastern Christian residents. Having recovered its position as capital after many centuries, Jerusalem also regained some of the establishments that had long been absent from the city. It was once again a royal city and had a royal palace which, after various locations, was finally constructed on the site of the Herodian palace to the south of the citadel. Jerusalem had a mint, a royal treasury and other institutions of government. This was a far cry from the position it had held under Muslim rule, when, after initial eminence under the Umayyads, the city had taken on a role subordinate to the new provincial capital of Ramleh.

Jerusalem on the eve of the Crusades

Just over four and a half centuries had passed since Jerusalem had come under Muslim rule. In AD 614, after a twenty-day siege, Byzantine Jerusalem had been conquered by the Persians. Although the city was recaptured fourteen years later by Emperor Heraclius, the Persian victory of 614 heralded the approaching end of Christian Jerusalem. Two decades later, between AD 636 and 638 the Holy City fell to the Muslim army of Caliph ‘Umar.1 For the next four and a half centuries Jerusalem was held by a succession of Muslim military governors representing foreign rule: the Umayyads ruling from Damascus until 750, the Abbasids from Baghdad until 878, the Egyptian Tulunid caliphate from 868 to 905 and Fatimid caliphate from 969 until 1073. In June of that year the Turkish Seljuks took the city and in 1098, one year before the arrival of the army of the First Crusade, Jerusalem reverted to Fatimid rule.

In general, under the Muslims the physical layout of Jerusalem differed little from that of the Byzantine city. The only major change was the eleventh-century reconstruction of the city wall in the south, which left the City of David and Mount Zion outside the walls, and the realignment of the north-west wall somewhat further to the west. However, major alterations were made to the urban infrastructure by the construction of many new and remarkable public buildings. The most important of these were the Dome of the Rock, the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Umayyad palaces south of the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharîf).

The population of Jerusalem in the Fatimid period approached twenty thousand.2 It was a diverse amalgamation of Jews, various communities of Eastern Christians and Muslims.3 Several hundred years after the Islamic conquest, the Muslims may still not have been the majority and do not appear to have been entirely in control of the city.4 Christian and Jewish pilgrimage continued, in spite of the difficulties and dangers involved.5

Nasir-i Khosraw described Jerusalem as a great city with strong walls, iron gates, high, well-built bazaars and paved streets.6 The Seljuk occupation of the city from 1073 until 1098 has left no evidence for any major construction in that period. However, there is evidence for a religious-intellectual revival in the city after a certain spiritual drought under the Fatimids.7 In August 1098, the Fatimids under the command of the vizier, al-Afdal ibn Badr al-Jamâlî, reoccupied Jerusalem. In preparation for the anticipated arrival of the Crusader armies, which by that time were approaching Antioch, the Fatimid governor Iftikhâr al-Dawla stationed in the city a large, well-trained army augmented by a special Egyptian corps of 400 élite cavalry. The Muslims prepared for the arrival of the Crusaders by strengthening the city walls, particularly in the north, where they built or strengthened an existing barbican and ditch, and on Mount Zion, where they cut another ditch and possibly reconstructed the forewall.8 Residents of surrounding villages moved inside the walls, and the greater part of the Christian population was expelled from the city to the outlying villages. The latter was a precaution against possible treachery on the part of the Christians, who were understandably suspected of harbouring aspirations of a return to Christian rule.9

Conquest and occupation in the twelfth century

On 27 November 1095, in the town of Clermont in central France, Pope Urban II called on Western Christianity to organize an army to free the Holy Sepulchre from the hands of the infidel. In the following year a great crusade was organized and set out for the East.10 On the morning of 7 June 1099 the army of the First Crusade arrived at a hill subsequently known as Montjoie, from where they could see Jerusalem in the distance. This was probably Nabi Samâwil, one of the highest hills in the Judaean Mountains and traditional site of the burial place of the prophet Samuel, located 7.5 km north-west of Jerusalem. By dusk they were camped outside the city walls. The six-week siege of Jerusalem, the culmination of the three years of the First Crusade, began.

According to the Frankish chronicler, William, archbishop of Tyre, on the Frankish side there were some 1,500 knights, 20,000 foot-soldiers and 18,500 followers. On the Muslim side there were an estimated 40,000 well-equipped soldiers.11 Iftikhâr al-Dawla set up his headquarters in the citadel (the Tower of David) located beside the western gate, and the citizens, mostly Muslims and Jews, were stationed along the entire length of the walls. Acc...