![]()

PART I

Foundation

![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Is Courage?

I think courage is walking into a building that you know could collapse at any minute, to try to save others.

—A witness to the 2001 World Trade Center towers tragedy

(From Phillips, 2004)

Henry, the boy with an operable cancer who feels fortunate just to have been alive. He lives every moment as fully as he can. Henry has so much dignity in the face of death.

—From Phillips, 20041

As a classroom teacher in an urban, poverty-stricken, school district, I encounter courage on a daily basis. Sometimes it is in witnessing a single mother with 3–4 children who is struggling to make ends meet while not allowing her little ones to experience anything but the love she has to offer. Other times courage radiates from the first grader who has trusted her teacher enough to tell her that somebody is beating her at home. Courage is strength from within, but from the outside—observing it, courage is simply awe-inspiring.

—Gina

Stories of courage exist in the heroes of history as well as in common people in our everyday life. Courage can be a virtue, a state of mind, an attitude, an emotion, a force, or an action. Establishing a psychology of courage is difficult, however.2 When we encounter obstacles and fears, we do not know whether courage is best manifested in overt overcoming or in covert endurance, in confrontation or in persevering and suffering. Hard work toward self-actualization does not qualify one to be courageous, but hard work toward overcoming pain and fear does.3 What seems plausible for one gender as courageous behavior may seem inappropriate for the other. Courage certainly means many things for individuals, families, and communities as depicted by various cultural and spiritual traditions.

The Psychology of Courage

Courage, simply put, refers to a willingness for risk taking and movement forward in the presence of difficulties. When we ask a question, such as what is courage, we also ask the questions of courage for what purpose and for and to whom our courage is directed. Courage finds its expressions in our thoughts, feelings, and actions. We cannot help but notice that the acts of courage are characterized by selflessness and other directedness. Courage is an intrinsic life force that allows us to recognize the goal of the common goodness as we seek our own actualization.

In this book, we hope to approach the conceptual understanding and the use of courage from the vantage point of Individual Psychology. Courage, as a psychological construct, is best addressed in Adler’s positive, phenomenological, and pragmatic approach of understanding human nature, family influence, and our characteristic approach to meet the life demands of work, love, and society.

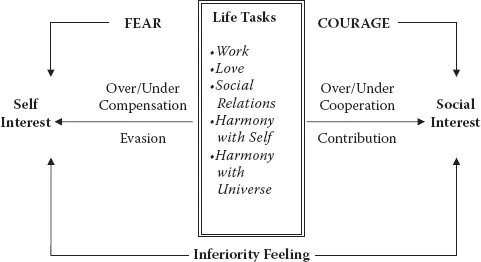

Adler was the pioneer to the systems thinking that we are only part of the whole and, thus, life is never perfect for the individual. The discouraged individual operates from the fear of failure, and lacks acceptance and courage for imperfection. The discouraged individual resorts to an exaggerated feeling of inferiority that propels his/her excessive attempts to strive toward success by overcompensation or self-preservation or by undercompensation or evasion in some or all life tasks (see Figure 1.1).

We believe that Adler’s mature theory is the psychology of courage that provides us the best roadmap by which the virtue of courage and its corequisite characters become teachable. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, we approach the basic life tasks of work, love, and society (family/friendship), and the existential tasks of being (harmony with self) and belonging (via equality and harmony with the universe) as they are relational and have to do with our attitudes toward living that we acquired in our early social living. Our fear of rejection and failure is the root of all problems. Comparison and competition is our typical coping method in the home, at school, and at work. The answer to these difficulties is courage. Change is possible when we modify our attitude of self-interest to social interest by the courage to cooperate and to contribute.

Figure 1.1 The Individual Psychology model of courage. Copyright 2008 by Julia Yang.

InFEARority

Courage is not the absence of despair; it is rather, the capacity to move ahead in spite of despair.4

A commonality exists in the various definitions of courage discussed in the philosophic, military, and religious literature. That is, adversarial conditions must be present prior to the occurrence of courage. Courage is a response to danger, despair, or fear. Fear is central to courage; it must be present for courage to exist.5 When we sense danger, fear takes us immediately to the need of self-preservation. As a response to danger, fear functions like an alarm system with the goal of protection. Fear is a gift when it, in working with our intuition, serves as a signal to our survival.6

Our fear is heightened when we encounter the world around us, the world with us, and the world within us. We fear rejection, failure, and mistakes. We are afraid of what others may think of us and, therefore, we are afraid to be ourselves. We are afraid of death and, therefore, we live in fear. Fear is finding a lump where there should not be a lump. We are afraid of loss and change. Fear is a device we use to bridge between our past and the unknown future. Fear follows us just like a shadow follows everything under the sun.

Fear is basic, normal, and necessary until it grows larger than our danger. In that case, fear becomes anxiety. Fear provoked by tangible situations or unidentifiable reasons is mostly faceless, lurking within us when least expected. Unfounded fear, however, can exercise its power over us and become worry or anxiety. Anxiety strips away our freedom and isolates us from the ironically intimidating world. Unlike fear, anxiety lacks identifiable sources and it arises from being torn between our expectations and the discrepant realities. Existentially, fear is about our ultimate death and its manifestations in our feelings of doubt and meaninglessness in the midst of our everyday living.7

In Individual Psychology, fear is more than an emotion. Fear serves a purpose for those who feel inferior and incapable of meeting the demands of the world. Fear can be used as hidden hostility that disguises an individual’s choice of negating contribution or not moving forward to his other responsibility for self and others. Adler used fear and anxiety interchangeably. Adler saw anxiety as the apprehension of social living. Anxiety is the manifestation of the striving of those with incomplete feelings (inferiority) to their goal of completion (superiority), although such striving takes them further away from their desire to connect to the society to which they wish to belong.

The new goal [prevention of a visible or felt defeat] presents a new form of life in sharply delineated features. Since due to fear of failure everything must remain unfinished, all striving and movement turn into pseudo-activity which, at least on balance, takes place on the useless side.8

When we operate from fear, we allow fear to dominate our thoughts, feelings, and actions. We often respond to fears with what would lead to a momentary sense of okayness or control within ourselves or with others. Deep down, we know we compromise who we are, and our true desires and needs are not met. When fear outweighs our problem, it makes our development and adjustment challenging as we relate to ourselves and the world. When we are constant captives of fear, we become restricted and blind to the world and what it can offer. It can take away our vitality and vision. Fear can stop our forward movement. Fear can hinder our sense of being and belonging. In our extreme fear, hostility toward self and the other (instead of harmony) becomes the prevalent way of response to conflict. In our inFEARority, living becomes helpless, hopeless, and meaningless. In our fears of defeat or not making it, we feel inferior.

Inferiority

Biologically speaking, we were all born feeling small, dependent, and helpless. Whereas the physical inferiority may be realistic, the psychological feeing of inferiority is acquired as we began to interact with our caretakers, siblings, and, later in our formative years, playmates and peers in home and school. Although true inferiority should exist only in a physical sense, our feeling of inferiority is mostly our subjective and evaluative perceptions that influence our behaviors and feelings. A sense of being “less than” or in a “minus” position may lead the individual to either a universal feeling of inferiority or an exaggerated inferiority complex.9 The inferiority feeling exists not only individually, but also collectively and spiritually. Our sense of belonging is deeply hindered when the feeling of less than is joined by the presence of social inequalities and an absence of meaning of life or spiritual connection.

Fear and inferiority work to either propel us for socially useful action or lead us to the feeling of inadequacy. Inadequacies are safeguarding devices that deprive us from our freedom and responsibilities of living. Instead of contributing to the main tent of community life, fear and inferiority encourages us to create sideshow activities that distant ourselves from resolving the problems of love, work, and friendship.

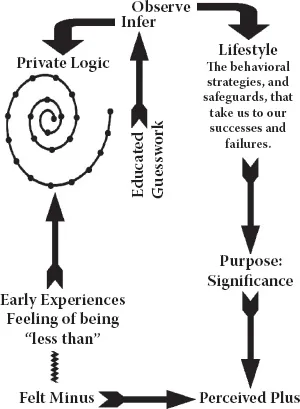

We respond to the inferior feeling with a natural desire to strive from the felt minus or our feeling of being less than to our private sense of superiority or perceived plus (Figure 1.2). This psychological movement is motivated by our innate creative power that manifests itself in our adoption of behavior strategies and emotions, and safeguards devices for self-preservation. This creative power gives us individual uniqueness while it generates the goal in response to our environment and, thus, takes us to success or failure. In addition, it privately moves us from the felt imperfection toward perceived perfection or a sense of purpose/significance/belongingness. The creative power of each individual generates movement toward unique life goals that were established early in life. In this movement, our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors are consistent with our private logic as well as our life plan (also see the discussion of striving in Chapter 9).

Figure 1.2 Felt minus to perceived plus. Copyright 2005 by Al Milliren.

According to Adler, we live in our mental world in a particular style. Our memory, perception, emotions, imagination, and dreams all convey the individual unity and uniqueness of how we think, feel, and act. He named this unity life style. Life style, therefore, is “the totality of the behavioral strategies and safeguards that take us to our successes and failures.”10

Our life style allows us to use our experiences differently as we assimilate impressions, accept or reject challenges, decide on our subjective understanding, and evaluate how to be the best in our social life. It is “a guide, a limiter, and a predictor.”11 Our fear-driven inferiority (or superiority) is manifested in our life style by which we make use of our circumstances as our creative power creates obstacles as well as options as we cope with life demands.

The behavior of the entire great life movement … is a striving from incompletion to completion. Accordingly, the entire individual life line has the tendency to overcoming, a striving for superiority.12

Our life style is a cognitive map of how we creatively move from the feelings of being less than to the goal of better than. As fear is manifested in inferiority, courage is present as the creative power that motivates the individual’s movement toward the chosen goal. The timid or safeguarding individual often meets challenges with blaming, wishful thinking, selfcentering, double mindedness, competition, fictional life goals, and other methods that create a need for undue attention, power struggles, revenge, or depression. On the contrary, the profile of a courageous individual is characterized by the absence of self-serving interest, safeguards, exploitation, and superioritty, and the presence of aesthetics, agape, altruism, courage, hope, empathy, meaning, endurance, movement, stillness, coherence, encouragement, reconciliation, wholeness, regeneration, and social connectedness.

Compensation

The threat to our courage comes largely from our lack of preparedness, which is masked as our fear. The fundamental problem for an individual lacking courage is the fear of making mistakes. Our discouraged or less than feeling becomes worse when it is interlocked with a society that is mistake centered. It seems as though the harder we try to be good, or better than, the worse our problems will become. Our fear is mostly guided by the fictional goal of perfection and the sense of superiority as compensation in response to our feeling of inferiority even when we are motivated by the desire to be useful.

There can be positive effects from obstacles if one looks at selfdevelopment as a process. Our creative power is the motivating force that helps us gear our inferior feelings into our compensatory self-ideal. The compensation processes are attempts to overcome felt minus. Our compensatory striving is the motivating force that brings our movement toward the self-ideal. As we imagine this ideal ...