eBook - ePub

Narrative

A Critical Linguistic Introduction

Michael Toolan

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 272 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Narrative

A Critical Linguistic Introduction

Michael Toolan

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This classic text has been substantially rewritten. Narrative explores a range of written, spoken, literary and non-literary narratives. It shows what systematic attention to language can reveal about the narratives themselves, their tellers, and those to whom they are addressed.

New material includes sections on gendered narrative, film narrative and a discussion of ways in which the internet and global television are changing conceptions of narrative.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Narrative è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Narrative di Michael Toolan in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Sprachen & Linguistik e Sprachwissenschaft. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 Preliminary orientations

1.1 Teller, tale, addressee

What is narrative? What do we mean by ‘narrative structure’? Where does a linguistic approach come in, and how helpful can it really be? The following are introductory notes on these and other basic issues, which should at least indicate the terrain to be covered, and why it is significant.

Commentators sometimes begin by stating the truism that any tale involves a teller, and that, therefore, narrative study must analyse two basic components: the tale and the teller. But as much could be said of every speech event: there is always inherently a speaker, separable from what is spoken. What makes narratives different, especially literary or extended spoken ones, is that the teller is often particularly noticeable. Tellers of long narratives can be surprisingly present and perceptible even as they unfold a tale that ostensibly draws all our attention, as readers or listeners, to other individuals who are within the tale. As a result we may feel that we are dividing our attention between two objects of interest: the individuals and events in the story itself, and the individual telling us about these. Thus when we read Coleridge’s ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ or Bronte’s Wuthering Heights or listen to the rambling anecdote of a friend, part of the experience is the activity of ‘reading’ or scrutinizing the character of the teller: the returned mariner, Lockwood, the friend. Already the two literary examples cited involve an enriching complication. In both texts mentioned, there is more than one teller: besides the mariner, for instance, is a ‘higher’ teller who writes, ‘It is an ancient Mariner/And he stoppeth one of three’. But we can address such complications later, and should concentrate here on narrative’s dual essential foci, teller and tale.

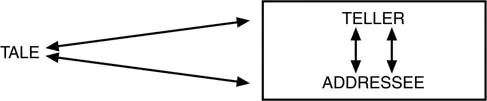

The possibility of achieving this effect of divided attention exploits a basic characteristic of narrative. Narrative typically is a recounting of things spatiotemporally distant: here’s the present teller, seemingly close to the addressee (reader or listener), and there at a distance is the tale and its topic. This selection of effects of closeness and distance can be represented graphically:

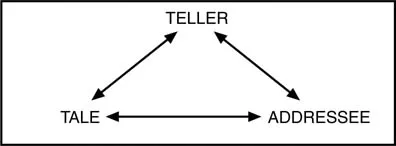

But since the present teller is the sole access to the distant topic, there is a sense, too, in which narrative entails making what is distant and absent uncommonly present: a three-way merging rather than a division. Diagrammatically this merging-and-immediacy can be represented as:

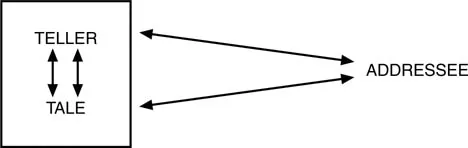

However, since tellers can become intensely absorbed in their self-generated sense of the distant topic they are relating, addressees sometimes have the impression that the teller has withdrawn from them, has taken leave, so as to be more fully involved in the removed scene. This third type of relation between tale, teller, and addressee (a withdrawing and merging) might be cast thus:

In short, narratives always involve a Tale, a Teller, and an Addressee, and these can be ‘placed’, notionally, at different degrees of mutual proximity or distance. Hawthorn (1985) broaches these same issues, taking a painting by Millais, The Boyhood of Raleigh, as capturing something central to narrative. In that painting an old seaman, with his back to the viewer, appears to be addressing two young boys who are evidently fascinated and absorbed by what he tells them. The old man is using his whole arm to point out to the sea, visible in the distance. But the boys’ eyes are on the man and his gesturing arm, not any distant scene he may be designating.

Narrative focusses our attention on to a story, a sequence of events, through the direct mediation of a ‘telling’ which we both stare at and through, which is at once central and peripheral to the experience of the story, both absent and present in the consciousness of those being told the story. Like the two young boys we stare at the ‘telling’ while our minds are fixed upon what that telling points towards. We look at the pointing arm but our minds are fixed upon what is pointed at.

(Hawthorn, 1985: vii)

One of the distinctive characteristics of narrative concerns its necessary source, the narrator. We stare at the narrator rather than interacting with him as we would if we were in conversation; at the same time, in literary narratives especially, that narrator is often ‘impersonalized’, and attended to as a disembodied voice.

Thus there is a teller in every tale to a far greater degree than there is a speaker in any ordinary turn at talk. Because narratives are, relative to ordinary turns of talk, long texts and personalized or evaluated texts, there is a way in which, while your conversational remarks reflect who you are (your identity and values), in the course of any narrative the narrator’s text describes that narrator. In brief snatches of conversation, a person may be able, through accent-mimicry for example, to ‘pass’ for someone of a different class or gender or ethnic identity; but to take on another’s identity in a sustained fashion, across a number of personal narratives, is ordinarily very difficult, and may even imply disabling confusion or a personality disorder. The reflection/description contrast may be chiefly a matter of degree, but it is arguably an important contrast with far-reaching consequences – e.g. even for assessments of mental health or illness.

This brings us to another important asset of narrators: narrators are typically trusted by their addressees. In at least implicitly seeking and being granted rights to a lengthy verbal contribution, narrators assert their authority to tell, to take up the role of knower, or entertainer, or producer, in relation to the addressees’ adopted role of learner or consumer. To narrate is to bid for a kind of power. Sometimes the narratives told crucially affect our lives: those told by journalists, politicians, colleagues, employers assessing our performance in annual reviews, as well as those of friends, acquaintances, enemies, parents, siblings, children – in short, all those which originate from those who have power, authority or influence over us. Any narrator then is ordinarily granted, as a rebuttable presumption, a level of trust and authority which is also a granting or asserting of power. But this trust, power and authority can be exploited or abused, as is reflected in literary critical discussion of ‘unreliable narration’. Narrative misrepresentation is a complex process, difficult to unravel. One exemplification of it arises far from literature: in criminal cases of serious fraud. Where, after having pleaded not guilty, a defendant is found guilty, the sentencing judge often refers to the obfuscating detailed deception that has been uncovered as ‘a complex tissue of systematic distortion and fabrication’, or uses a similar revealing description.

Even before we attempt a working definition of narratives, it is clear that these are typically ‘cut off’ in some respects from surrounding co-text and context (their verbal and non-verbal environment, respectively: the former comprises any language that precedes or follows the narrative, the latter includes anything non-verbal of relevance, including the situation and the identities of teller and addressee). Narratives often appear to stand alone, not embedded in a larger frame, without any accompanying information about the author or the intended audience: they’re just ‘there’, it seems, like pots or paintings, and you can take them or leave them. They differ, at least in degree, from more transactional uses of language, as when someone asks you a question, or makes a request or a promise or warning: in such cases there is strong expectation that the addressee will respond or act in predictable ways. So some of the normal constraints on how we make sense of discourse seem to be suspended. And it seems we do not always have to relate narratives directly and immediately to their authors, or socio-historical backgrounds.

1.2 Typical characteristics of narratives

We can begin to define narrative by noting and inspecting some of its typical characteristics:

1 A degree of artificial fabrication or constructedness not usually apparent in spontaneous conversation. Narrative is ‘worked upon’. Sequence, emphasis and pace are usually planned (even in oral narrative, when there has been some rehearsal – previous performance – of it). But then as much could be said of, for example, elaborate descriptions of things, prayers, scholarly articles.

2 A degree of prefabrication. In other words, narratives often seem to have bits we have seen or heard, or think we have seen or heard, before (recurrent chunks far larger than the recurrent chunks we call words). One Mills and Boon heroine or hero seems much like another – and some degree of typicality seems to apply to heroes and heroines in more elevated fictions too, such as nineteenth-century British novels. Major characters in the novels of Dickens, Eliot, Hardy, etc., seem to be thwarted (for a time at least) in roughly comparable ways. And the kinds of things people do in narratives seem to repeat themselves over and over again – with important variations, of course. Again, prefabrication seems common in various types of writing and visual spectacle besides narrative, although the kinds of things mentioned above seem particularly to be prefabricated units of narrative.

3 Narratives typically seem to have a ‘trajectory’. They usually go somewhere, and are expected to go somewhere, with some sort of development and even a resolution or conclusion provided. We expect them to have beginnings, middles, and ends (as Aristotle stipulated in his Poetics). Consider the concluding words of children’s stories:

And they all lived happily ever after;

since then, the dragon has never been seen again.

and notice the finality and permanence conveyed by the ever/never pair. Or consider the common story-reader’s exit-line:

And that is the end of the story.

which has near-identical counterparts in the closing sequences of radio and television news bulletins. All these examples mark this attention to the expectation of closure and finality, itself just one aspect of the broader underlying expectation of narrative trajectory. Relatedly, the addressee is usually given to understand, and does so assume, that even embarking on their story the teller knows how it ends up (not the precise wording, but the event-based or situational gist). Exceptions to this might include Dickens’s serialized novels, and the bedtime story that a parent makes up for a child, impromptu. Even these, along with more planned-outcome narratives, can be distinguished from both diaries and live commentaries, in that in the latter new intervening acts, beyond the control of the witness/reporter, can dictate the shape and content of the report. In true narratives, arguably, the teller is always in full control although, like Dickens and the bedtime storyteller, they may not fully foresee at the outset that material which they will control.

4 Narratives have to have a teller, and that teller, no matter how backgrounded or ‘invisible’, is always important. In this respect, despite its special characteristics, narrative is language communication like any other, requiring a speaker and some sort of addressee.

5 Narratives are richly exploitative of that design feature of language called displacement (the ability of human language to be used to refer to things or events that are removed, in space or time, from either speaker or addressee). In this respect they contrast sharply with such modes as commentary or description. Arguably there has to be some removal or absence, in space or time, for a discourse to count as a narrative. Thus if I listen in my car to a radio running commentary on a simultaneously-occurring football match or funeral, this approaches the status of narrative by virtue of spatial displacement (it is not a narrative at all if I am at the football match directly witnessing, and listening to the radio commentary). But live commentaries, like real diaries, breach characteristic 3 above, and are arguably not narratives at all. More borderline are edited TV highlights of sports and other events (interestingly, one rarely finds edited highlights of matches and events on radio).

6 Narratives involve the recall of happenings that may be not merely spatially, but, more crucially, temporally remote from the teller and his audience. Compare our practices with those of the honeybee, whose tail-wagging dance overcomes spatial displacement, in that it communicates about distant sources of nectar, but cannot encompass temporal displacement. Thus it can only signal to its chums back in the hive immediately upon its return from the nectar-source. Accordingly, the honeybee’s tail-wagging is no proper narrative in our sense, but merely a kind of reflex observation. As Roy Harris has remarked:

Bees do not regale one another with reminiscences of the nectar they found last week, nor discuss together the nectar they might find tomorrow.

(Harris, 1981: 158)

This is a lovely image (or narrative), partly because in fact it is something that (as far as we know) we humans alone do, and no other animals – even those with simple language systems.

A first attempt at a minimalist definition of narrative might be:

a perceived sequence of non-randomly connected events

This definition recognizes that a narrative is a sequence of events. But ‘event’ itself is really a complex term, presupposing that there is some recognized state or set of conditions, and that something happens, causing a change to that state. The emphasis on ‘non-random connectedness’ means that a pure collage of described events, even given in sequence, does not count as a narrative. For example, if each member of a group in turn supplies a one-paragraph description of something or other, and these paragraphs are then pasted together, they will not count as a narrative unless someone comes to perceive a non-random connection. And by ‘non-random connection’ is meant a connectedness that is taken to be motivated and significant. This curious transitional area between sequential description and consequential description is one of the bases for the fun of a familiar party game in which people around a table take turns to write a line of a ‘story’, the other lines of which are supplied, in secret, by the other participants.

The important role of ‘change of state’ has been celebrated in the more linguistic term transformation by the structuralist Tzvetan Todorov (1977: 233):

The simple relation of successive facts does not constitute a narrative: these facts must be organized, which is to say, ultimately, that they must have elements in common. But if all the elements are in common, there is no longer a narrative, for there is no longer anything to recount. Now, transformation represents precisely a synthesis of differences and resemblance, it links two facts without their being able to be identified.

The one-line definition of narrative also suggests that consequence is not so much ‘given’ as ‘perceived’: narrative depends on the addressee seeing it as narrative – the circularity here seems inescapable. While most would agree that the traditional novel is a narrative, there can be legitimate disagreement as to the status, as narrative, of less familiar and complex structures. For example, imagine you enter a cartoonist’s studio and find three frames, on separate pieces of paper, on his desk. They have quite different characters, settings, furniture, etc., and seem to be about quite unrelated topics. They seem to be rough drafts, because on the corner of one is a coffee-ring, where the cartoonist has carelessly left a cup, and on the second one there’s a food stain in the top corner, while the third has some cigarette ash and a coffee r...