eBook - ePub

Constructing Place

Mind and the Matter of Place-Making

Sarah Menin, Sarah Menin

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 352 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Constructing Place

Mind and the Matter of Place-Making

Sarah Menin, Sarah Menin

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This book is a cutting edge study examining the attitudes to both nature and the built environment of the designer, the client and the society in which an intervention (be it architecture, landscape design or a piece of art) is made. The legacy of the Modernist view of nature and the environment is also addressed, and the degree to which such ideas continue to impinge on contemporary interventions is assessed.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Constructing Place è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Constructing Place di Sarah Menin, Sarah Menin in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Architecture e Architecture générale. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 Mind

Projecting a relationship

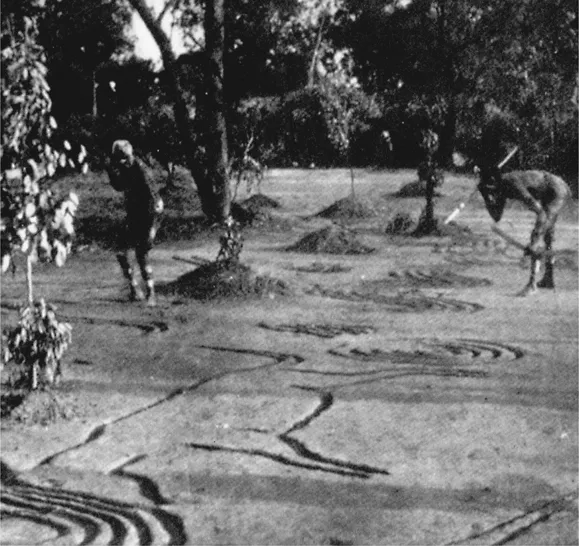

Plate 3 Bora ground showing the images carved with sticks that indicate the path

From Lindsey Black, Bora Ground, Sydney: Booth, 1940

Chapter 1

The aesthetic in place

Introduction

I want to begin with a quotation and then a question.

At night we went up to Greasy Lake.

Through the center of town, up the strip, past the housing developments and shopping malls, street lights giving way to the thin streaming illumination of the headlights, trees crowding the asphalt in a black unbroken wall: that was the way out to Greasy Lake. The Indians had called it Wakan, a reference to the clarity of its waters. Now it was fetid and murky, the mud banks glittering with broken glass and strewn with beer cans and the charred remains of bonfires. There was a single ravaged island a hundred yards from shore, so stripped of vegetation it looked as if the air force had strafed it. We went up to the lake because everyone went there, because we wanted to snuff the rich scent of possibility on the breeze, watch a girl take off her clothes and plunge into the festering murk, drink beer, smoke pot, howl at the stars, savor the incongruous full-throated roar of rock and roll against the primeval susurrus of frogs and crickets. This was nature.1

Now my question is, Is Greasy Lake a place? Perhaps by the time we come towards the end of this essay, we shall be able to answer it. And, if so, what kind of place? But if we cannot respond, can we dismiss the question?

‘Place’ has become an ‘in’ word. From the mass media to advertising, from the travel industry to the real estate industry, from sociology to geography, the fascination with place testifies, I suspect, not so much to the discovery of a hidden value as to a widespread if unconscious lament over its absence. Many of us, particularly in the industrial world, inhabit anonymous environments whose bland sterility is disguised by shiny plastic and glass surfaces. We live and work in industrialized landscapes of insular factories, strip malls and office towers, moving with clockwork regularity along highways that are self-propelled conveyor belts to faceless apartment buildings and generic suburbs. Yet we dream of some ideal place where we shall truly be at home. Besides creating an insatiable market for paradise in the form of idyllic vacations or escapes to exotic lands, the placelessness we suffer from reinforces –and perhaps epitomizes–a culture of dissatisfaction.

Yet what constitutes place? Many disciplines offer many answers, ranging from simple location to the intensely present, self-transcending experience of sacred space. Our understanding and respect for the importance of place have widened and deepened from the work undertaken over the past thirty years. But there is one dimension of place that is easily overlooked, a dimension that may be the most critical of all because it concerns experience of the most primary sort –aesthetic. Our understanding of place, multi-faceted though it be, can be enlarged still more from an increased awareness of its aesthetic dimension. To reveal this often hidden, often misunderstood dimension is what I want to undertake here. Further, I want to explore the possibility that, in grasping the aesthetic character of place, we are not merely identifying another aspect of this complex idea but rather are probing its very centre. Like Plotinus’ sun, the aesthetic radiance of place illuminates its every appearance, even as its intensity decreases the further we go from its source, until place merges with the all-encompassing darkness of its negation.

Some determinants of place

In its most basic sense, place is the setting of the events of human living. It is the locus of action and intention, and present in all consciousness and perceptual experience. This human focus is what distinguishes place from the surrounding space or from simple location.2 Humanistic geographers emphasize this anthropocentric meaning, a meaning that comes about through experience.3 Place for them is the location of experience. It is realized as a set of ‘environmental relations created in the process of human dwelling … internally connected with time and self … Place thus provides an organizing principle for … a person’s engagement or immersion in the world around’ him or her.4 This most general condition is basic to an understanding of place, but by being basic and general it does not say enough about what is distinctive and memorable in this fundamental idea.

Some things can be said about place generally that few would contest. One of these is a special sense of physical identity that a location can convey. Certain qualities set it apart. It may be a physical unity conveyed through topographical features, such as being bounded by hills or mountains, or being partly or wholly surrounded by water. On the other hand, identity may be conferred by a central reference point rather than a boundary, such as a harbour, a mountain, or a monumental building, such as a church, temple or mosque. On a more modest scale, a centre may be a village common or square, a great or venerable tree, a monument, or a great pole.

Physical coherence is another trait that can convey a sense of place. A high degree of architectural similarity or compatibility may create the sense of a distinctive place. This is especially the case when it contrasts with other, nearby areas, as in a historic district, the old centre of a large city, or an architecturally distinguished new development. This last raises the issue of perceived value. A suburban development built to one or two conventional models has architectural coherence. But while this imparts identity to the neighbourhood, it is not likely to convey the feeling of enhanced presence that we associate with place. Coherence may also be conveyed by boundaries –as in an urban square, common or plaza –or a bounded interior space –such as the walls of a room or a house. We may realize place in a neighbourhood or town that possesses a high degree of coherence relative to its scale. This may be true, as well, of a region, such as a mountainous area or a coastline. Specific examples of all these may come easily to mind, but I hesitate to mention any here for fear of deflecting consideration of the validity of the idea by a dispute over particular cases.

Of course physical characteristics alone do not create place. Cultural geographers are right in joining the human factor to these features. Whether this connection comes about through actions, practices or institutions, or through the simple presence of a conscious, sensing person, it is in the interaction of human sensibility with an appropriate physical location that place acquires its distinctive meaning. One common form that this takes is when locations acquire historical or cultural associations. Sometimes these predominate in generating identity to a location not otherwise distinguished, as may occur with the site of a battlefield or a massacre, a building or site where an important document was signed, or the birthplace or home of a famous person. In such instances, place depends not so much on its physical characteristics as on the aura with which our knowledge about it invests the location. Personal memory may imbue an area with a similar distinction.

Such features, then, as distinguishing physical identity and coherence, together with the consciousness of significance, can contribute to the sense of a distinctive presence that we associate with the special character of place. These are important and they need to be carefully specified in each individual case. But there is, I think, something more to the special quality of place, a dimension that is not so much a physical characteristic or a cultural layer of meaning as something that underlies these more articulable features. This is its aesthetic dimension.

Let me develop this in two directions. One is to suggest a descriptive account of the aesthetic experience of place. Like any such description, aspects of it will be peculiar to the individual case and the personal experience, while other aspects will be characteristic of a cultural sensibility. Yet perhaps some features will possess a generality that may be theoretically useful. My second purpose is rather different. It is to draw out some of the implications of this description of experience for the design of place, or rather for designing the conditions in which a full experience of place can occur.

The aesthetic in place

We ordinarily think of aesthetics as referring to art, to the value that distinguishes the arts from other, more ordinary, objects and occasions. At times we readily ascribe this value beyond art to nature, as when we admire a landscape or delight in the intimate wonder of a spring flower or glorious sunset. But what can this aesthetic value have to do with place?

To deal with this question we need to focus not on the occasion or the object we call beautiful, but on the experience we have at such times and places, and on the qualities and characteristics of the situation of which that experience is a part. For what we value here lies, I think, not wholly in a work of art or a natural occurrence but in the conditions under which we encounter them and in what takes place. What, then, characterizes such an aesthetic situation?

To answer this, it is important to return to the etymological origins of the term itself.5 The word ‘aesthetic’ comes from the Greek aisthesis, literally perception by the senses. For Baumgarten, who in 1750 identified it as a distinct discipline, aesthetics is the science of sensory knowledge directed towards beauty, and art entails the perfection of sensory awareness.6 This observation is not only historically important; it sets the scene for understanding the field of aesthetics squarely on the basis of sense perception. Moreover, there can be no perception, direct or imaginative, without the body and, as it is human experience we are concerned with, the conscious, active, human body. Given the development of the field of aesthetics into complex theoretical issues in the ensuing two and a half centuries, it is important to reaffirm this sensory connection. Aesthetic perception then becomes not a purely conscious act and not a merely subjective occurrence; rather it is grounded in the human body and the existential conditions of human life. These conditions are important to specify because they bear directly on our understanding of the aesthetics of place.

People are embedded in their world –their life-world, to use an important term from phenomenology. A constant exchange takes place between organism and environment, and these are so intimately bound up with each other that our conceptual discriminations serve only heuristic purposes and often mislead us. For instance, we readily speak of an interaction of person and object or person and place, but the term ‘interaction’ presupposes an initial division that is then bridged. Yet in the most basic sense of existence, there is no separation but rather a fusion of things usually thought of as discrete entities, such as body and consciousness, culture and organism, inner thought and an external world. Therefore we may understand the setting of human life as an integration of person and her or his environment.7

As humans we are inescapably embedded in a life-world that incorporates our physical bodies, our personal and communal histories, our social education and practices and, not least, our cultural ethos. Perception is integral to our experience of that world, and this means that the aesthetic is grounded in the very conditions of living. Perception, howeve...