eBook - ePub

French Management

Elitism in Action

Jean-Louis Barsoux,Peter Lawrence

This is a test

- 208 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

French Management

Elitism in Action

Jean-Louis Barsoux,Peter Lawrence

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This fascinating book is an account of management in the contemporary French business world. The formal nature of work relations and the rituals of French business life are analyzed and set against the role of senior executives, and the book looks at the corporate culture of four leading, but very different companies

* Michelin

* L'Air Liquide

* L'Oreal

* Carrefour.

Also included is an examination of general management attitudes to labour relations, and the book includes an overview of the distinctive features of French management, future trends, and the changes that further European integration may or may not bring.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

French Management è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a French Management di Jean-Louis Barsoux,Peter Lawrence in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Business e Business General. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 Déja vu et jamais vu

FRANCE IS BOTH DIFFERENT AND DIFFICULT for outsiders to apprehend. But the quality of the difference should inspire the effort. France with its style and élan, its economic achievements and inflexibilities, its paradox of equality and elitism, and of individualism and insecurity, is the best 'society-mystery' on offer in Europe.

France of course has a strong image in the wider world. It is not one of those wishy-washy countries about which people can think of nothing meaningful to say. It is the most visited country in the world. France is not bland, it is not colourless; it evokes reactions, foreigners have views about it (often strong views) and people often have strong visual images of France as well.

Yet this image enjoyed by France in the wider world also lacks balance. It has more to do with history than geography, more to do with politics than economics, and has more to do with traditional luxury goods than with the technologies of the later twentieth century.

The image also tends to be a little dated. There is a touch of the First World War about it, of ugly subsidized apartment housing, and dubious public urinals. The gaunt impersonality of the state predominates while in this image the cosiness and comfort of northern Europe seems to be lacking.

Yet this mild tendency of foreigners to fix France in the past involves another misapprehension, an inclination to under-estimate. The plight of France for the first half or more of the twentieth century is less than fully recognized abroad, as indeed are the recovery, growth, and achievements of France in the second half of the century.

First the plight. Industrialization in France during the nineteenth century was less far reaching than in say Britain, Germany, or the USA, and France entered the twentieth century with a more traditional occupational structure and less manufacturing capacity than these countries. France had already been defeated once by Germany (Prussia) in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the only achievement this experience afforded France was that of paying off its reparations to Prussia in three years rather than the scheduled five, and thereby securing the withdrawal of the Prussian army of occupation in double-quick time.

Again while France was on 'the winning side' in the First World War (1914—18), rather like its neighbour and ally Italy, it emerged from the war looking more like a defeated nation than a victor. French loss of life had been considerable, the north of France had been endlessly fought over and mostly occupied by the Germans for four years, and the French came to the Versailles Peace Conference of 1918-19 in a mood that combined resignation and desperation as they struggled to establish safeguards and guarantees against future German aggression.

They failed. In the spring of 1940 the Germans did m six weeks what they had failed to do in four years in the First World War — they conquered the whole of France. Another four years of German occupation followed compounded by the indignity of submitting to the rule of the Vichy government — a right-wing, socially retrograde, collaborationist regime supported by the Germans at war while it suited them.

The euphoria of the Liberation in the summer of 1944 was intense, reaching its high point in the liberation of Paris on 20 August 1944. With the benefit of hindsight we can see that the German threat to France had been ended for all time, but that was not immediately obvious at the end of the War.

What was obvious was the depletion of France's national resources, looted by the Germans or destroyed in the fighting, the dislocation that went with the overthrow of the Vichy regime, and the need for help that eventuated in France being a massive beneficiary under the European Recovery Programme, more popularly known as Marshall Aid, and instituted in June 1948.

But even in the early years of peace, new problems arose. General de Gaulle's provisional government, set up at the time of the Liberation, gave way to the Fourth French Republic (1946-58) that both presided over the early stages of economic recovery and introduced some progressive social legislation. Yet this regime was unstable, a bewildering succession of prime-ministers, elections, crises, and ministerial reshuffles. And the Fourth French Republic was dogged by colonial problems.

The French Colony of Indo-China had been occupied by the Japanese during the Second World War. After the war the French tried to re-assert their control over it, and failed. The rising tide of local nationalism and independence movements proved too strong for the French in Indo-China as they were for the British in India and the Dutch in Indonesia. Indeed the French were routed in a conventional battle, Dien Bien Phu in 1954, rather than undermined by guerrilla warfare, the stock-in-trade of anti-colonial insurgents. This debacle was not the end. The same year saw the start of the Algerian uprising which proved more protracted, nearer to home, and more damaging politically and morally.

Again with the benefit of hindsight 1958 rather than 1944 is probably the turning point for France, the date after which good news predominated bad news, the end of its twentieth-century woes.

In 1958 the Fifth Republic was inaugurated, with de Gaulle as President. The political instabilities of the former Fourth Republic seemed to be banished for all time. Indo-China was repackaged as Vietnam, and the problem passed to the Americans. The Algerian problem was solved within five years, admittedly by simply 'giving it away' (granting independence) but this was the only viable solution and could be implemented by a leader of de Gaulle's stature whose patriotic devotion was beyond doubt.

De Gaulle also worked for the rapprochement with Germany building a strong relationship with West Germany's first (post-war) chancellor, Konrad Adenauer. Later generations have come to take peace in at least Western Europe for granted, but there was nothing taken for granted about it in the time of de Gaulle and Adenauer.

Meanwhile economic recovery and indeed growth had begun, and there are a number of factors involved. First of all the post-war government inaugurated a succession of five-year plans, that designated particular industries, such as cement and transportation, as national priorities because of their importance for reconstruction. Later on, these five-year plans became more a matter of political window-dressing than of economic substance, but in the early days of the Fourth Republic they were real and had the merit of designating priorities and of focusing national endeavour. These five-year plans also had the secondary advantage of bringing together politicians and civil servants on the one hand and industrialists on the other, and of achieving a loose consensus of views and objectives. This state-industrialist-manager consensus is a leitmotiv of the present book, but it is important to add that it had a certain novelty in the early years after the Second World War, a time in which many industrialists had discredited themselves and their class by collaborating with Nazi Germany via the Vichy regime.

Second, in the early post-war years France benefited from Marshall Aid, and received more under this scheme, the European Recovery Programme, than any other European country except Britain. It is a relatively minor theme, but in the same period France also benefited from the administration of their occupation zone in Germany after the war. Here they repossessed the fruits of earlier German looting, taking back for example railway rolling stock. They looted on their own account. And they fixed the terms of trade between France and the French Occupation Zone of Germany, forcing the Germans to export from the Zone to France at fixed (low) prices, and to import from France at fixed (high) prices.

Third, France benefited from the post-war growth in world trade and from the unprecedented economic growth in the industrialized world during the period after the Second World War. This growth occurred throughout the Western World, and is independent of the policies of particular regimes and their five-year plans. In France this period is dubbed les trentes glorieuses, the 30 glorious years of economic growth and the enhancement of real incomes, a period that seemed to come to an end with the first oil shock of 1973-74 and its attendant inflation.

Fourth, but rather more difficult to pin down, there is probably in the post-war period a collective resolution in France to advance and succeed economically. This resolution was a long time 'in the making', and owes much to the adversarial relationship between France and Germany over the previous hundred or so years, where it was assumed that part of the German (military) success stemmed from industrial superiority. This new resolution in France was also a reaction to the country's recent economic history. As noted earlier French industrialization in the nineteenth century was far from complete; the First World War strained and drained the nation, and the inter-war period (1918-39) was marked by economic stagnation. The resolution to succeed economically is in the spirit of 'Goodbye to all that'.

The magic year of 1958 had a further significance. Not only did it inaugurate a generation of Gaullism, end the instabilities of the Fourth French Republic, presage the solution of the Algerian problem, and consolidate the Franco-German rapprochement; 1958 also saw the inception of the European Economic Community (EEC), or Common Market in popular parlance, with France as a founder member alongside Germany. In the contemporary debate it is clear that founding the EEC was seen as a critical event in France, as a rendez-vous avec l'histoire. At the time setting up the EEC was a decisive event, a real challenge that would expose France to the rigours of European competition, i.e. to German competition; and on the whole, this was a challenge to which French industry rose.

Another feature of the post-war period was the emergence in France of various high-tech industry and product success stories, in a country famous primarily for various luxury goods — the grands vins, champagne, cognac, haute couture, and so on. It is probably fair to say that these have now become familiar stories — the TGV high-speed train, success in civil and military aviation, in helicopters, in high-tech armaments, in telecommunications, in rocket launching, nuclear power, and so on — but they do represent a new development in the second half of the century and when aggregated they impact substantially and favourably on the image and reputation of France.

As the twentieth century draws to a close, France is a member of the G7 Group of major industrial countries, has a GNP per capita substantially higher than that of Britain, and is the world's fourth largest exporter after the USA, Japan, and Germany. Moreover, the country is secure, has no major foreign enemy, no fear of Germany, and is free to opt in and out of NATO at will! All this would have seemed very unlikely when the century began.

Power, orders, and ambiguity

So far we have suggested that France is peculiarly susceptible to misapprehension; that it is easy, for instance, to underestimate both the woes of France in the first half of the twentieth century and its triumphs thereafter, and thereby to have too little sense of the change that France has undergone.

The problems are not entirely in the eye of the (foreign) beholder. The inclination to misapprehension is in part attributable to certain paradoxes in French society, to certain inconsistencies of volition among French people. Consider in this connection — and it is very relevant to an understanding of behaviour in business organizations — the French response to authority.

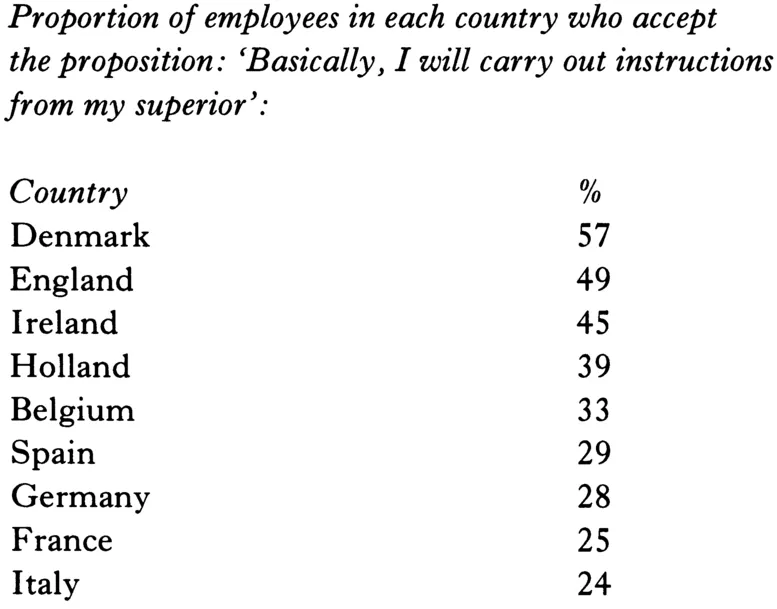

A German writer, basing his views on the findings of Germany's famous public opinion survey firm, the Allensbach Institut, has produced the following comparisons (Ackermann, 1988):

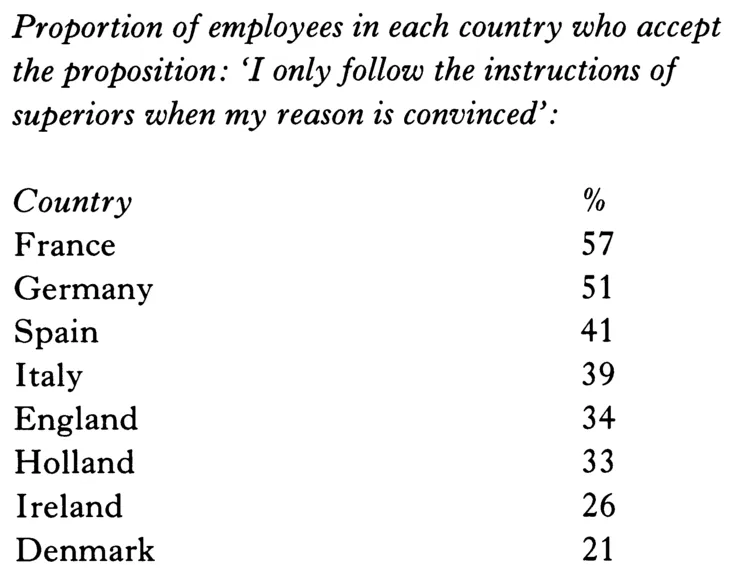

Here, one may feel, is the stroppy individualist Frenchman we all know: folk wisdom verified by social science! The next line in Ackermann's table seems to support this view:

A nice consistent picture: France is nearly bottom of the first list and on top of the second, probing the same phenomenon from opposite directions.

Now let us juxtapose another finding from a different source, The Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede surveyed and tested employees of the same American multinational company in some 50 countries. His broad finding is that there are substantial differences in work-related attitudes and values from country to country, revealed by his extensive and unique sample (Hofstede, 1980). But he further systematizes his findings by ranking the respondent countries on four dimensions, two of which are germane to the French authority paradox.

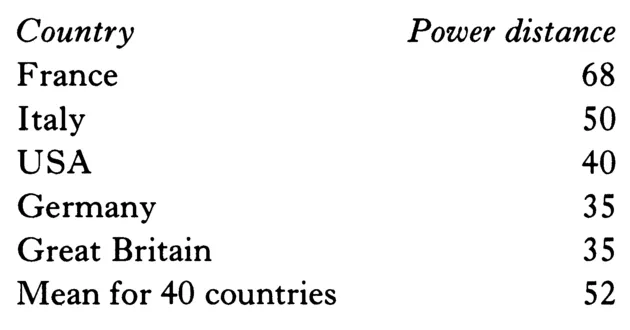

The first of these is the dimension of power distance, or the willingness of people in different cultures to accept differences in the power possessed by individuals; and remember that in industrial societies power distance refers primarily to differences of power enjoyed by people at different levels in formal organizations. Here are the French, in comparison with a few other countries (Hofstede, 1980, 315):

Note that the higher the number, the greater the tolerance for inequalities of power. Is it not intriguing that the French, who are less willing to take orders, are more willing to accept that some people have much more power than others?

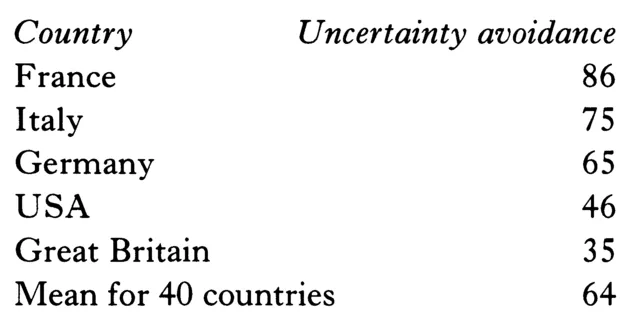

There is another bit of this jigsaw in the form of Hofstede's second principal dimension. This is uncertainty avoidance, or the desire to eliminate ambiguity and doubt, to know where you stand, to leave little to chance. This uncertainty avoidance is not constant throughout the world, but again varies from country to country, and France is distinctive (Hofstede, 1980, 315):

As with the previous table on power distance, the higher the figure in the uncertainty avoidance column the stronger the desire to avoid uncertainty. This finding is again intriguing, since a standard remedy for reducing uncertainty is to accept orders — but the French are reluctant to do this. So we have an apparent contradiction between French attitudes to orders (negative) and to power differences (positive), and between desire to avoid uncertainty (positive) and uncritical acceptance of orders as the means to this end (negative).

We have demonstrated these contradictions not in order to give a full and lucid explanation at this stage — though they are explained in the body of the book — but to signal the subtlety and complexity of the issue. Where the French are concerned, stereotypes will get us to the starting line but not to the finishing post.

The idea can be expressed differently. Some societies are seamless garments, so that management and behaviour in work organizations are not compartmentalized. In the USA for example, management st...

Indice dei contenuti

Stili delle citazioni per French Management

APA 6 Citation

Barsoux, J.-L., & Lawrence, P. (2013). French Management (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1616465/french-management-elitism-in-action-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Barsoux, Jean-Louis, and Peter Lawrence. (2013) 2013. French Management. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1616465/french-management-elitism-in-action-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Barsoux, J.-L. and Lawrence, P. (2013) French Management. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1616465/french-management-elitism-in-action-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Barsoux, Jean-Louis, and Peter Lawrence. French Management. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.