![]()

1

THE JEWISH VOICE

Chicken Soup or the Penalties of

Sounding Too Jewish

In his most recent novel Philip Roth again evoked the specter of what it means to sound too Jewish. Projecting his anxiety about the formation of an American-Jewish literary identity on to his image of England, Roth has his unnamed protagonist tell the following anecdote. He has seen a commercial on British television in which a “youngish middle-aged, rather upper class English actor” begins to remove his makeup having just performed Dickens's Fagin. “To relax after the performance he lights up one of these little cigarillos, contentedly he puffs away at it, talking about the flavor and the aroma and so on, and then he leans very intimately into the camera and he holds up the cigarillo and suddenly, in a thick, Faginy, Yiddish accent and with an insinuating leer on his face, he says, ‘And, best of all, they're cheap.’ ”1 The protagonist's immediate response is to phone an Anglo-Jewish friend to ask him about the commercial. He is admonished that he will “get used to it.” “It” being British anti-Semitic representations of the Jew. But the protagonist worries about such insults, as well as being criticized for making “such a fuss about being Jewish.”

It is, of course, not being Jewish which is the problem against which Roth's figure protests, but sounding Jewish. The “Faginy, Yiddish” accent marks the stage Jew as different, as not really belonging to cultivated British society with its Oxbridge accent. Roth's protagonist protests by calling his Anglo-Jewish friend and speaking with him in his American-accented English. He must sound different, but this difference is in no way represented in Philip Roth's text. Philip Roth writes a clear, mid-Atlantic literary language, undifferentiated from the language of most other contemporary American writers. Indeed if Martin Amis's most recent novel, London Fields, with its American-Jewish novelist-protagonist is any indication, it is the language of modern socially critical fiction, even to British ears. And yet the fear of sounding different, sounding too Jewish (which may well mean sounding too “New Jersey” in the ear of Roth's imagined British listener) haunts Philip Roth's work.

Roth's critique of the British image of the Jew mirrors the anxiety which his protagonist has about his command of his own language, not the Yiddish-accented language of the anti-Semite's image of the Jew, but the language of high culture, the literary language of the Anglophone novelist. Jews, according to Roth, compulsively tell stories: “With the nigger it's his prick and with the Jew it's his questions. You are a treacherous bastard who cannot resist a narrative …” (93) It is the Jewish author's command of the language of the narrative, the language in which the questions are asked, which is drawn into question.

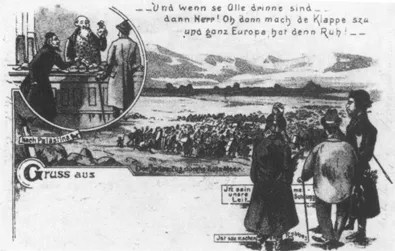

The creation of the image of the Jew who is identifiable as different because he or she sounds “too Jewish” provides a model through which we can see the structure of the image to create an absolute boundary of the difference of the Jew even as this boundary historically shifts and slides. Jews sound different because they are represented as being different. Jewish authors have felt compelled to respond to this image of difference, and to create a counter image of the Jew who sounds Jewish, for within their creation of texts, Jewish authors are Jews who sound Jewish. Within the European tradition of seeing the Jew as different, there is a closely linked tradition of hearing the Jew's language as marked by the corruption of being a Jew. In the British fin-de-siècle journal The Butterfly [PLATES 2–3] there are images which associate a specific Jewish physiognomy with a specific manner of speaking. Not merely a “Jewish” accent, but an entire discourse about capital and trade which was supposed to characterize the Jew. In a German postcard of the same period [PLATE 4] the rising interest in Zionism is linked to the language of the Jews. The caption reads: “And when they are all in there, then Lord, then close the gate and all Europe will have peace.” The language of the Jews in the boxes next to their bowed legs has them speak nonsense (in a Yiddish-accent dialect) to match their Eastern European Jewish clothing: “Now our people are crazy” and “Let's now make a rabbi.” The Jew's true nature as a usurer is revealed in the inset. All of these Jews are represented as acting Jewish but also as sounding Jewish.

What does it mean to sound too Jewish? I have argued in my study Jewish Self-Hatred that there is a long tradition of representing the “hidden” language of the Jew as a signifier of specific difference.2 And that the difference represented is always an attempt to present the qualities of the Jew (usually negative, but sometimes, indeed, positive) as separate from the referent group. The image of the “Jew who sounds Jewish” is a stereotype within the Christian world which represents the Jew as possessing all languages or no language of his or her own; of having a hidden language which mirrors the perverse or peculiar nature of the Jew; of being unable to truly command the national language of the world in which he/she lives or, indeed, even of possessing a language of true revelation, such as Hebrew.

The stereotype of the Jews' language is rooted in the earliest history of the rise of Christianity (or rather in the separation of the early Church from Judaism) and is mirrored in a static manner in a series of texts—the Gospels, or, as the early Christians referred to them, “The New Testament”—which were generated dynamically over time.3 As early as Eusebius and Athanasius (in the fourth century ACE) these texts become the central canon of Christianity as the so-called “pseudo-Gospels” (such as the Gospel of Nicodemus) are removed. In the Gospels, Christians are given a representation of the Jew who sounds too Jewish and a direct message about the inherent difference of the Jew. It is in the continuity of the Gospels at the center of Christianity—not in the theology or indeed in the practice of the Church—that the representation of the Jew who sounds too Jewish is preserved. And it is to this central stereotype that Western (that is, Christian or secularized) society turns when it needs to provide itself with a vocabulary of difference for the Jew. Thus it is quite unimportant whether the Gospels (or the “Q” document) were first drafted in Aramaic or Greek. What is central is that in the reception of the Gospels there is a contrast between the language of the Gospel narrative (whether Greek, Latin, German, or English) and Jesus' ipsissima verba.4

The creation of the image of the Jew who sounds too Jewish in the reception of the Gospels can be understood by examining/comparing four analogous passages. Let us turn to the Gospels in their canonical (i.e. received) order and read one passage, the last words of Christ in all of them. Focusing on the presentation, we see that in the first set of passages Jesus Christ speaks in Aramaic. Matthew, the first gospeler, represents a Christ whose last words are as follows: “And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, ‘Eli, Eli, Lama Sabachthani?’ that is to say, My God, My God, why has thou forsaken me?” (27: 46). Mark has Christ “at the ninth hour … [crying] with a loud voice, saying ‘Eloi, Eloi, Lama Sabachthani?’ which is, being interpreted, My God, My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (15: 34). This significance of this lies in the presentation of Christ as speaking the language of the Jews: his words need to be translated into Greek, Latin, German, or English for the self-labeled Christian reader to understand. The reader is thus made aware of the foreignness of Christ's language— he speaks the language of difference; he is a Jew who sounds Jewish. Placed in the mouth of Christ, the “hidden” language of the Jews is the magical language of difference. It generates a positive image of difference. But it still labels him as a Jew.

But in the second (“later”) set of passages, Christ speaks directly to the reader. If we take the parallel passage from Luke we can trace the same course with very different results. Christ is taken to Calvary and there he is crucified. “And when Jesus had cried with a loud voice, he said, Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit: and having said thus, he gave up the ghost” (23: 46). In John, the

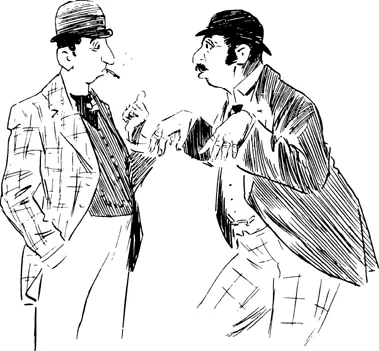

“ Vy d'you vcar all dem ringth, Ithaacth? ”

“ Vell, you thee, I travelth a good deal, and ven I gets into conversation with a gentleman, ten to vun I thells him a ring, don'd yer know.”

“ But all the sthoneth itli tinned inthnle.”

“ You thilly fool ! I don'd talk like that !—

PLATE TWO

The image of the “cheap Jew” is linked with the Jew's corrupted language in a short-lived “humorous and artistic periodical ” from the fin de siècle. The periodical also published a series of “Ghetto Travesties” in which the same device was used. Language and gesture were closely linked in determining the meaning of the Jew's language at the fin de siècle. Gestural language was understood by anthropologists of the day such as John Lub-bock as a sign of the primitive state of a culture. The image of the “cheap Jew” is here evoked by language, gesture, and physiognomy. The Butterfly (May—October, 1893) (Source: Private Collection, Ithaca).

1 talks like thith ! ! !”

PLATE THREE

last of the Gospels which related the life of Jesus, Christ is taken to Golgotha and there “he said, It is finished: and he bowed his head, and gave up the ghost” (19: 30). His language needs no translation; it is transparent, familiar not foreign. The later Gospels provide a verbal sign of difference between the image of the Jews and that of the early Christians represented in the text—Jews who were at the time becoming Christians in a world in which the valorized language was Greek. As Christian readers who read through the Gospels in their canonical order, we thus abandon the image of Christ as one who sounds Jewish and replace him with the image of one who sounds like ourselves (whether we speak Greek, Latin, German, or English). He becomes a Christian. Thus the existence of a “hidden” language which would mark Christ as a “real” Jew, i.e., as a non-Greek-speaking Jew and therefore of lower status, was impossible.

In Luke and John there is no need for translation or interpretation. The language of this passage is completely transparent to the Christian reader of the Gospels. The reader of the passage understands that Christ speaks the same language as the reader. This “lucanization,” according to Morton Scott Enslin, “reflects a marked sameness of tone, [a] smoothness and freedom from the

PLATE FOUR

A turn-of-the-century postcard representing the German fantasy of the nature of the Jew. Rooted in the stereotype of the Eastern Jew, this image depicted all Jews in Germany. The use of “ Yiddish ” words which could be so recognized in this context meant evoking the hidden language of the German Jews, their fantastic inability to do anything but Mauscheln (Source: Private Collection, Ithaca).

little idiosyncrasies which stamp the man himself….”5 This movement in the Gospels from the image of Christ as a Jew who sounds too Jewish to that of the Christian whose discourse is separate and distinct from that of the Jew, becomes clearest in the writings which codified the views of the early Church. In Acts, Peter's first speech to his fellow Jews in Jerusalem is recounted in a manner that differentiates between Greek, the language of his readers (now feeling themselves as “Christians”), and the representation of the Jews' discourse. He writes, for example, “And it was known unto all the dwellers at Jerusalem; insomuch as that field is called in their proper tongue, Aceldama, that is to say, The field of blood” (1: 19). But the utterances of Jesus in Acts never needs this type of translation. His language is consistently accessible. His language is not the language of the Jews.

A similar movement of the text is to be found in the recounting of the defense of the first Christian martyr, Stephen. The movement away from the “hidden” language of the Jews reveals itself to be more than a rejection of the language of the Jews. It is also an appropriation of the discourse of the Jews which Stephen reveals to the reader as having been misused by the Jews themselves. By stripping away the polluting nature of the “hidden” language of the Jews Stephen reveals to the reader that the very discourse of the Jews was never really their own.

Stephen, a Greek-speaking Jew, had begun successfully to evangelize among the Jews. He was prosecuted by Jewish priests who brought false witnesses to accuse him of blasphemy. His defense is quite extraordinary. He begins by recounting to his Jewish accusers a synoptic history of the Jews as represented in the Torah from the appearance of God to Abraham through the building of the Temple to—the coming, death and resurrection of Christ:

Ye stiffnecked and uncircumcised in heart and ears, ye do always resist the Holy Ghost: as your fathers did, so do ye. Which of the prophets have not your fathers persecuted? and they have slain them which showed before of the coming of the Just One; of whom ye have been now the betrayers and murderers … But he, being full of the Holy Ghost, looked up steadfastly into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing on the right hand of God … (Acts 7: 51–55)

The entire story of the Jews is reduced to a preamble to the coming of Christ. The sense of continuity between the “real” Jews of the past and the “new” Jews of the early Church, between the “true” Jewish experience actually written “on the heart” and not merely inscribed on the skin, becomes his defense. The act of circumcision, the traditional sign of the special relationship between the (male) Jew and God, becomes here a false sign, a sign written on the body of the hypocrisy of the hidden language of the Jew. The continuity between the Torah and the Gospels, the Christian demand that the Jews of the Torah prefigure (and thus are replaced by) the Christian experience removes the discourse of the Jews about their own history from their own control. As St. Augustine stated in his manual for new converts to Christianity: “the New Testament is concealed in the Old; the Old Testament is revealed in the New.”6 The Torah suddenly becomes the Old Testament. The “hidden” language of the Jews disappears from the tradition of the early Church, even though it is preserved in what now comes to be called the “New” Testament as a sign of the difference of Christ's nature from that of the Jews. The successful separation of the “Church” from the “Synagogue” is indicated in the latest of the Gospels, Revelations, as well as in the Pauline epistles, where the separation between the divine discourse of the Church and the corrupt discourse of the Jews is absolute.

The rhetoric of European anti-Semitism can be found within the continuity of Christianity's image of the Jew. It is Christianity which provides all of the vocabularies of difference in Western Europe and North America, whether it is ...