![]()

1 Introduction

Locations of Desire

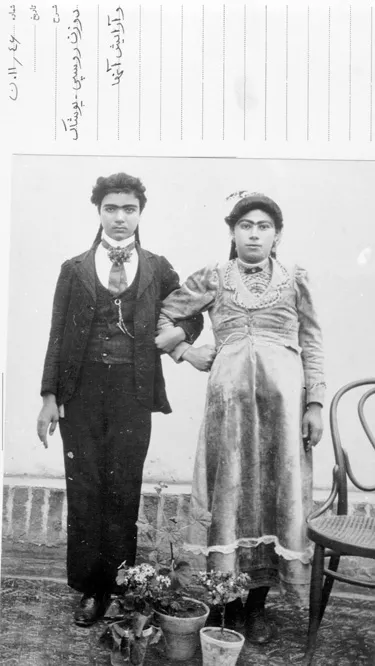

Two women from the Qajar era (1785–1925) in Iran are posed together, standing on a rug in front of potted flowers, which were generally considered a masculine prop in Qajar photographs of men (Figure 1.1).1 The one on the left is dressed in a man’s European suit, complete with tie and pocket chain, while the one on the right is in a European dress. Their arms are linked with both staring straight into the camera. Both their eyebrows and light mustaches have been accentuated, most likely by silver nitrate2 or by sormeh. The description ascribed to their unknown identities is “Two female prostitutes—their clothing and makeup.” This image evokes many questions—why were these women posed as a heterosexual couple? What did they deem as prescriptive of being a “man” and “woman” in this masquerade? What was the purpose of this image? Why are they categorized as “prostitutes,” and why are their clothes and makeup representative of this profession? But most importantly to this study, what were their desires in staging this photograph, and for whose desire was it composed?

Within this photograph, as well as in other photographs from the Qajar era, how does one locate the notion of desire, and even so, why should it be assumed that photographs contain or exhibit desires? Within the temporal time and space constituted by the frame or through the long expanse of time, in which the photograph continues to endure even after the sitters have died, how can desire as an intangible thing become manifest and expressed, if it is indeed there? My inquiry is inspired by Homi Bhabha, whose own work in turn was inspired by both Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975) and Frantz Fanon (1925–61) and sought to elucidate the location of modern culture within colonial and postcolonial literature that was anchored in neither an atavistic past nor a Eurocentric prescription, but somewhere in the liminal spaces between, in the everydayness events of one’s life that straddle various modes of time, what Bhabha calls “double-time.”3 Similarly, the photograph as a representation of the everyday could allow one to know something about “desire” in Qajar Iran, however minimal a photograph is able to transmit information to those viewing in the future.

One may ask, “Why desire?” Perhaps this type of investigation invokes neo-Orientalist sentiments of framing the Middle East in terms of sexuality, but what is at stake here, however, are two points: (1) photographs illustrating persons revolve around interpretations of the human body; and (2) if the body is the main focus of particular photographs, such as portraits, ethnographic studies, and erotica, then the representation of the body has the potential to provide information about gender, sexuality, and desire within a particular era and/or context, however idealized. One “reads” the body to extricate social identity markers as human bodies present some sort of signage that requires decoding. With that said, when one poses in front of the camera, how the body is portrayed and perceived in the photographic space becomes of importance—the pose is theatrical, constructed, and predicated on preconceived notions of how that body should look and perform. Until faster and cheaper photographic technologies of the Technical Revolution of the 1880s, the slower exposures of photographs made one even more cognizant of the body, pose, and message. Moreover, the performing of these notions of gender and sexuality in photographic spaces was and is inextricably weaved and in dialogue with ideas of the nation and its ideologies and its spaces whether mainstream or liminal. So, how did one make a “desirable” photograph in Qajar Iran?

Figure 1.1 “Appearance of a prostitute woman”; description on the Ministry of Culture card: “Two female prostitutes—their clothing and makeup,” undated. Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (IICHS), Tehran ( 275–131274). http://www.iichs.ir/. Throughout this book, I argue that Qajar Iran was in general an ocularcentered society predicated on what was seen and unseen, and photographs became liminal sites of desire that maneuvered “betwixt and between”4 various social spaces—public, private, seen, unseen, accessible, and forbidden—thus mapping, graphing, and even transgressing those spaces, especially in light of increasing modernization and global contact during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hence, the photograph became a vehicle to traverse multiple locations that various gendered physical bodies could not, and it was also the social and political relations that had preceded the photograph that determined those social spaces of (im)mobility. Indeed, one may ask how those conditions are different from any other cultural or geopolitical entity. Building on Foucault, Suren Lalvani has discussed how vision organizes spaces and social and political relations, so that eventually (the invention of) photography would not only replicate those a priori social relations but also entrench them, further emphasizing their ideological “normalcy”: “Vision is irrevocably tied to domains of knowledge, arrangements in social space, lines of force and visibility, and a particular organization of bodies.”5 Before photography arrived, Qajar Iran had had its own arrangements of socio-economic, political, and gendered spaces and “particular organization[s] of bodies,” which had differed from other places, including the Ottoman Empire (1299–1923) and Mughal India (1526–1857) before the British Raj (1858–1947). I am not speaking of how language organizes vision or how pre-existing visual cultures affected the aesthetics of photographs, however useful they may be. I am speaking of how the body—in terms of gender, sexuality, and desire—operated within these social and political relations through the apparatus of the photograph. What was seen or not seen in Qajar photography was determined ideologically by the social, cultural, political relations on the ground, which shape how one sees and organizes the world.

Although photography became a new, modern conduit that indexed and mapped multiple spaces in Qajar Iran, I am also primarily interested here in how photographs negotiated and coded gender, sexuality, and desire, becoming strategies of empowerment, of domination, of expression, and of being seen. In identifying these notions in photographs, one may glean information about how modern Iran metamorphosed throughout its own long durée or resisted those societal transformations as a result of modernization. In The Distorting Mirror (2007), Laikwan Pang makes an important inquiry that underlies my own study, but in relation to Qing China (1644–1912), that being “to discover whether photography introduced the Chinese to a new way of seeing gender, in terms of the significations mediated by technology, by modes of distributions and receptions, and by surrounding sociocultural structures and ideologies.”6 The resounding answer is “Yes!” as photography not only depicted existing gendered roles and stereotypes within society en masse but also participated in creating discourses that spoke of gender in new and different ways. The difficulty in assessing photography’s impact on social norms and expectations, however, is that its introduction to the world came at a time in the nineteenth century when many inventions and innovations, as well as being at the height of European colonialism, were already radically changing world cultures and practices. On one hand, it would be naïve to posit that the camera was only recording changes in gendered norms and practices as a result of modernization projects. On the other hand, it is certainly a challenge to posit the photograph as creating, expanding, and/or changing these norms and practices all on its own. As Pang rightly points out, the photograph mediates between its own agency to produce images within its existing “sociocultural structures and ideologies,” thus producing its own visual hybrid language.7 Although Pang’s text does not outright claim this, her text alludes to the idea that the photographic space is inherently a gendered space and a space for women, considering also that having one’s photograph taken was popular among upper-class Chinese women and courtesans: “The comparison between gender and photography is … a meaningful project, since gender, like photography, occupies an uneasy position between reality and construction.”8

While there have been a decent number of theoretical scholarship on gender in nineteenth-century Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Ottoman photographies (all of which could still be expanded), the potential to develop scholarship further on gender in relation to Qajar photography is quite vast and open. Minimal yet vital sections devoted to women photographers have been noted by photohistorian Yahya Zoka9 and representations of women by Mohammadreza Tahmasbpour,10 both of which have been elaborated on by Mohammad Sattari and Khadijeh Mohammadi Nameghi,11 Parvin Taaee,12 Carmen Pérez González,13 and myself.14 Scholarly discourses on Qajar photography only began in the late 1970s; thus, up until this point, much emphasis has been on identifying photographers and sitters in various archives, as well as attempting to identify photographic attributes that were specifically “Iranian.” Such early inventories were necessary to begin thinking about how these photographs operated sociologically, especially how photographs both depicted gender and sexuality, as well as changed those societal notions in Qajar Iran. Furthermore, much of the scholarship on Qajar photography has been more intent on demonstrating how special, advanced, and different Qajar photography was in comparison to particularly nineteenth-century European photography, which is usually unsatisfying and actually latently Eurocentric—this comparison with or against Europe is what has deterred scholars in thinking that Other photohistories may also be useful in nuancing Qajar photography. So as I embark on my own project, I do not suppose that Qajar photography is more special or advanced than any other photohistory, and I have attempted to include Other photohistories in addition to European ones. In fact, Qajar photography seems to have followed very similar “normal” pathways to most countries’ and colonies’ inductions to photography, catalyzed by imperial designs of cultural dominance.15 Certainly, I point out many instances in which Qajar photography was in contrast to several European traditions, especially in terms of erotic photography, because the photographic pornography market was inundated and dominated by the French—making it difficult to “provincialize Europe”16 in this particular case—but I hope to make these distinctions based on specific historical, economic, and sociocultural contexts, not on assumed formulae, nationalist sentiments, or solely on pre-existing visual phenomena as those conditions were fluid—not static—and photography played a dramatic role in changing (visual) cultures worldwide, as well a...