![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Nothing is so poor or so trivial as not to have a story to tell us. The tools, the potsherds, the very stones and bricks of the wall cry out, if we have the power of understanding them.

(Flinders Petrie, 1892)

If during a museum visit we temporarily suspend our viewing of the collections to quietly observe other visitors, we notice that people’s attention is not equally distributed among the objects on show. Rather, observation shows that some items are the focus of interest for many viewers, while others, which we term silent objects, are almost completely ignored, their presence barely acknowledged.1 Perversely, objects with a more conspicuous and attractive appearance benefit from fuller interpretation and glamorous display, while others are relegated to the ranks of supporters.

This is problematic for museums for several reasons. By focusing on the most conspicuous and visually compelling objects, visitors may miss much of the interest of an exhibition and fail to appreciate the full richness and depth of a topic. They may go away with a false image of the collections and an incomplete or erroneous view of the past. In addition, from a practical perspective, an uneven viewing pattern creates congested areas where visitors converge, leaving other spaces empty.

From the visitor’s viewpoint, an undue emphasis on certain objects restricts their freedom to identify where their interest truly lies and what they would appreciate seeing.

There are many reasons why some, silent, objects do not attract and hold attention. An inconspicuous appearance is a crucial factor. Overlooked objects are not exceptionally large or small, colourful, artistically noticeable, obviously ancient or precious looking, nor are they endowed with an iconic significance which makes them desirable to seek out. They are not as visually captivating as their more popular counterparts and, if they are not in a prominent location, people rarely even happen upon them by chance.

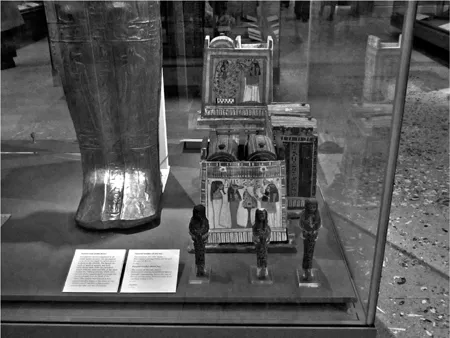

Figure 1.1 Three silent objects: shabtis at the feet of the gleaming gilded coffins of Henutmehyt in the British Museum. A few visitors look at the decorated shabti boxes, but the shabtis are ignored or even positively disliked (below, 8.5.3)

Source: © S. Keene, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

One might argue that this predicament could be simply resolved, for example, by placing the problematic objects in strategic positions within the room and by lighting them dramatically to increase their chances of being noticed. This stratagem could be employed effectively for some exhibits. However, if it were to be used to excess, it would cancel out the effect, which relies upon sensations of anticipation, on surprise, on the viewer’s assumption that the museum is offering a selection of particularly worthwhile attractions. In addition, although such a display may initially lure visitors to the object, it does not necessarily increase the potential of the item to hold the viewer’s attention for long enough for them to notice that it is interesting.

Research indicates that the appearance of objects contributes to the formation of split-second assumptions that visitors involuntarily or consciously make about the depth and quality of the experience that a specific object can provide.2 In a perfect world, each museum goer would visit the galleries with full awareness of the narratives on offer and of the objects’ roles in relation to these. However, this is rarely the case. When visitors are immersed in an environment in which display and interpretation is inadequate for them, they tend to retreat to contingent modes of selection and meaning-making strategies. They look at the most striking objects in view and they make sense of them using their pre-existing knowledge. They rely on the visual magnetism of some exhibits and on casual encounters with what is in their path. For these reasons, many objects are ignored during museum visits.

For example, one of the objects on display in the Horniman Museum’s Music room display, Listen to order, a glittering array of musical instruments organised according to type (see below, Figures 3.3 and 6.11), is a tiny pair of arms with hands, neatly fashioned out of bone. Only the meticulously organised or targeted visitor would notice these insignificant items. The label states that they are a pair of clappers from ancient Egypt, collected by the archaeologist Flinders Petrie (they may be the oldest item on display in that gallery). Those intrigued by the trajectory of an object’s history might discover from the online catalogue that these were acquired from Petrie by the son of the founder of the Horniman Museum. But what we don’t learn, which would be poignant indeed given the great attraction of the gallery for families and children, is that 3,500 years ago this pair and another were placed in the burial of a child for them to use on their onward journey and to console the survivors – a specific person, specific because they lived at a specific time in a specific place.3

Again, visitors to the spectacular Egyptian death and afterlife: mummies gallery overlook or even express boredom with the number of shabtis4 included in the displays (Figures 1.1 and 8.9). Were they to read one of the many informative text panels (considered to be too numerous by many visitors), they would learn that these little figurines were placed in burials from about 2000–2030 BC. Often inscribed with a magic spell, they were intended to carry out work on behalf of the dead person, who might otherwise have to labour in the fields or do other menial tasks. While at first only one or two were included in a burial, they were subject to shabti inflation, eventually to over 400 – one for each of the 365 days in the year plus 36 overseers.5

1.1 NEW RESEARCH

This book reports the findings from extensive research aimed at identifying the key factors which can transform the display of a silent object into an exciting and interesting encounter for the visitor. Ideally, all objects on show to the public would be exhibited so that their potential interest is evident. Yet, despite a wealth of information on the museum experience in general and on visitor interaction with objects in particular, museums still have not found optimal ways to exhibit less visually attractive objects. It is clear from the extensive published research into exhibition techniques that there is no magic solution that will cover all situations.

This unsatisfactory state of affairs stems from a focus on the core elements of the museum experience in isolation: visitor and exhibits; visitor and environment; visitor and visitor; environment and exhibits. Instead, any strategic intervention aimed at displaying silent objects effectively and hence rebalancing viewing patterns requires a combination of solutions based on the characteristics of the object, the exhibition setting, the nature of the museum and its visitors.

The visitor–object encounter is framed and encompassed by the nature and quality of three main parameters: the setting, which includes the gallery or museum and the other visitors present in the space; the visitor: their prior knowledge, experience of museum visits, whether they are on their own or with others, and their physical and mental state – fresh or tired, young, old, etc.; and the object or exhibit. Figure 1.2 depicts the transection of the three dimensions.

A comprehensive approach requires an analysis of the three aspects in combination: the physical and symbolic characteristics of objects; visitors’ cognitive and affective responses to them; and visitors’ responses to the setting and environment – all in the broader spatial and contextual scale of the museum visit. This process is comparable to the way in which one responds to a cinema scene, where the eye in turn focuses on different details of the picture, each individual element contributing to a facet of the scene, but with the overall background view always in sight.

Therefore, a programme of research addressed the challenge of enabling the voices of silent objects to be heard by conveying to the visitor the existence of interesting stories and creating the conditions for a rewarding experience. It addressed these specific questions:

• why do people choose or neglect specific exhibits?;

• what causes them to act in this way?; and

• what are the characteristics of the observed interactions?

Figure 1.2 Setting–exhibit–visitor: the combined elements of the museum experience

Source: © F. Monti/S. Keene.

A better understanding of these issues can inform a treatment of museum objects that increases visitor awareness of the rewards concealed behind their appearance. By studying people’s reactions to such objects in different display and interpretation scenarios, it is possible to understand the causes of their actions and lack of engagement, and consequently to address them.

The research has indeed helped us to understand the reasons for some objects’ silence. Further, it enables us to offer a range of techniques and practical guidelines on how to display and interpret them to better advantage. This could help to re-balance viewing patterns in museum galleries and enable people to make an informed choice of what they want to see and interact with.

The results are widely applicable to the display of objects in general rather than only silent objects. Instead, a set of general concepts and tools have been developed and are presented here that can be applied to the design and evaluation of any object display, showcase or gallery. This can provide a far deeper and more holistic understanding of the object-based information landscape of the museum than current tools can offer. This approach facilitates a re-balancing of the ‘attracting, holding and communicative power of objects’, whatever their visual qualities.6

We are encouraged in this by finding in two of the galleries we investigated a viewing pattern evenly distributed between spectacular and inconspicuous objects. Whether by chance or as a consequence, audiences spent longer in these two galleries than in other comparabl...