![]()

Part I

Objects and offerings

![]()

1

The forgotten things

Women, rituals, and community in Western Sicily (eighth–sixth centuries BCE)

Meritxell Ferrer

Introduction1

Despite the importance that gender studies and feminist perspectives have achieved in archaeology in the last decades, their impact has been quite limited in Italian archaeology. This is especially true for Italian archaeology of the Iron Age, where only in the last decade have a few works begun to consider questions of gender and women’s lives (Robb 1997; Whitehouse 2001, 2013; Cuozzo 2003; Gleba 2008; Perego 2011). In the field of the archaeology of Sicily during the first millennium BCE, studies of the colonies increasingly focus on gender, especially on intermarriages (Hodos 1999; Shepherd 1999; Delgado and Ferrer 2007, 2011a, 2011b; Péré-Noguès 2008), but almost none considers the active participation of women in the everyday life and development of the colonies (Delgado and Ferrer 2007, 2011a, 2011b). Moreover, such studies almost completely ignore native Sicilian populations. In fact, most studies related to the Italian peninsula and Sicily reproduce traditional views of gender in which agency, that is the ability to act with consequence, is granted only to men, particularly those understood to have a higher rank or status, in contexts traditionally interpreted as masculine, such as trade, production, politics, and the public sphere. Conversely, women are denied any capacity to act and hence any role in the success and growth of colonies.

Ruth Whitehouse (2013) has recently pointed out that the lack of interest in gender issues in Italian and, by extension, Sicilian archaeology responds to the maintenance of historical-cultural paradigms in its almost exclusive interest in describing different patterns to place material objects in a frame of space and time. Women, as well as children, elders, commoners – that is, everyone who is not a member of the male elite – simply do not fit in or contribute to the historical cultural paradigms that archaeologists implicitly assume in their analyses. Consequently, most studies ignore these “others” and thereby reinforce a view of society in which only elite males act and have agency. In the case of Sicily during the first half of first millennium BCE, we could add two more causes for the general neglect of women beyond the one highlighted by Whitehouse. First, archaeological practice from its beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century until relatively recently has been dominated by the archaeology of monumentality and objects. In Sicily, this long-held predilection has resulted in the exclusive examination of contexts traditionally associated with power – such as city walls and ritual spaces – as well as other contexts that potentially provide complete artifacts suitable for museum display, like cemeteries. This bias in the Sicilian archaeological record has taken place at the expense of other areas where gender studies could be more preeminent, such as the domestic context, which is usually considered to be both unrelated to power and, by extension, to the masculine sphere and less likely to produce complete objects. Indeed, only two domestic areas from western Sicily – four houses from Monte Polizzo (Mühlenbock 2008) and one from Monte Maranfusa (Spatafora 2003) – have been published.

The second reason for the lack of attention to gender issues lies in the hegemony of colonial archaeology and colonist discourses. The persistence of the gaze from the colonies – mainly the Greek ones, but also Phoenician ones – has led to a continued interpretation of colonist groups as the leading actors in any kind of action or change in the island. The local populations, on the other hand, have been traditionally imagined as being passive and static actors; they are mere recipients of the technological, social, and cultural advances of their “outstanding” colonial neighbors. As a result most studies of the native Sicilian world of the first half of the first millennium BCE place a very large emphasis on imported objects, especially those of Greek origin. In fact, these objects have been traditionally considered to be “exceptional” and have been granted a higher aesthetic, symbolic, or economic value based on a modern and subjective “ceramics hierarchy” made by archaeologists. On the other hand, artifacts that are not considered to be “extraordinary” have largely been undervalued. This is the case, for example, for the many objects of local production that have usually been categorized as artifacts of poor aesthetic, symbolic, or economic interest and placed in the lower levels of this imagined “ceramics hierarchy.” This is the category where all material objects related to the domestic sphere and, in particular, to activities traditionally associated with the world of women, such as cooking ware, can be found. Scant attention is paid to material culture related to the domestic sphere, especially to culinary practices, in most of the monographs and articles related to Sicilian acropoleis, the main ritual space of most native Sicilian settlements (see, for example: Castel-lana 1990, 1992; Vassallo 1999; Guzzone 2009; Panvini et al. 2009). This usual meager presence – or even absence – contrasts with the materials documented in these ritual spaces. On the acropolis of Monte Polizzo, for example, cooking ware accounts for 22.92 percent, while native plain ware accounts for 51.29 percent of all ceramic sherds recorded in this ritual space (percentages extracted from Morris and Tusa 2004, table 1).

Despite the challenges that the published archaeological records pose for any study of native populations, especially women, the main goal of this chapter is to recover the agency of some women in communal celebrations carried out periodically on the acropoleis of native Sicilian settlements, through the analysis of one of the largely forgotten objects strongly connected with domestic practices and, by extension, women: cooking ware, especially pignatte or cooking pots. To do this, first I analyze the acropoleis, as well as the meaning that these settings had for the local population of the island. Second, I review ritual practices carried on during these communal ceremonies, in particular feasting. Finally, I highlight how women constructed a sense of community and the hierarchical relationships within it, as well as created strong bonds between these ritual events and the daily world, through their ritual activities. The visibility of these women’s agency and ritual competence is possible when we consider ritual as an action, in particular as a specialized form of behavior that stresses some aspects of the daily life through some kind of performance (Bell 1992; Barrett 1994; Humphrey and Laidlaw 1994; Brück 1999; Bradley 2005). In this case, I explicitly consider the “ritualization” of the act of cooking that some women carried out in the periodic celebrations hosted on the acropoleis.

Sicilian acropoleis: Communal ritual spaces in Sicily during the first millennium BCE

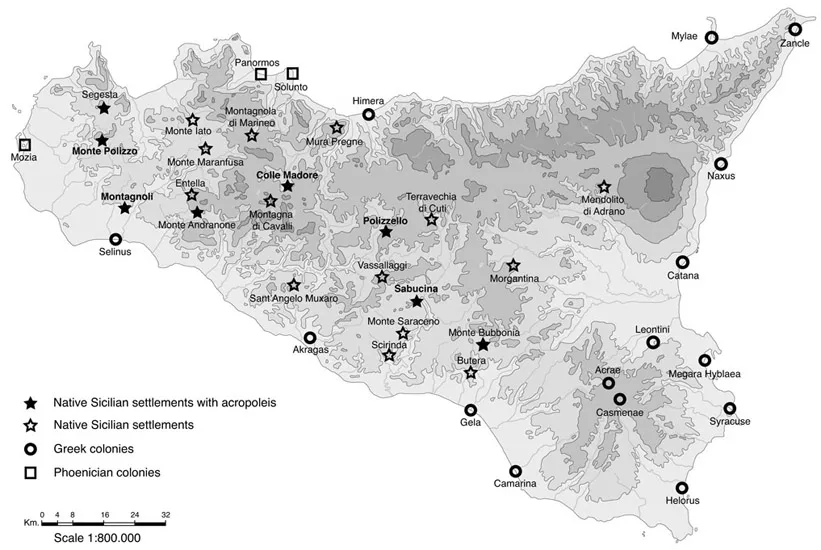

Since the end of the second millennium BCE and during all the first millennium BCE, native Sicilian populations mostly settled the upper part of certain hills. The settlements were placed at strategic points along routes of travel and transport and with easy access to the Sicilian river network, which favored convenient communication not only between them but also with the colonies scattered along the coast (Fig. 1.1). The elevated topography of these centers determined their internal organization, using the slope to distinguish, visually and spatially, the three areas that usually form these settlements. At lower levels were the cemeteries. At a second level were located the areas of habitation. Finally, at the highest point or in the most visually conspicuous area was located the acropolis, the place devoted to the periodic celebration of communal ritual ceremonies. This topographic placement endowed the acropolis with a visual and geographic dominance over the whole settlement, its surrounding areas, and the links established between them and the rest of the island (Ferrer 2010, 2012).

The prominence of the acropoleis was reinforced through architecture that stressed their monumentalization, distinguishing them from contemporary domestic contexts and maximizing their difference from the rest of the settlement (Ferrer 2010, 2012). This distinction was achieved through the use of Archaic architectural styles, such as circular buildings – as, for example, at Polizzello (Panvini et al. 2009), Montagnoli (Castellana 1990, 1992), or Monte Polizzo (Morris et al. 2002) – that were dominant in domestic architecture in western Sicily (second millennium BCE) until being gradually replaced with rectangular buildings (eighth to seventh centuries BCE) (Ferrer 2010, 2012). This distinction was also achieved by integrating elements belonging to foreign architectural traditions, such as the erection of a Phoenican stele-baetyl at Monte Polizzo (Morris et al. 2002; Ferrer 2012), the use of Greek silenic antefixes (Guzzone 2009), and the almost complete adoption of a Doric temple in Segesta used for native ritual practices (Burford 1961).

Another aspect of these communal ritual places is their high level of complexity and temporal dynamism. The acropoleis are quite large spaces, allowing the celebration of ritual events in which a considerable number of people assisted and participated. In most of these settings, there are several buildings, some devoted

Figure 1.1 Map of Sicily showing the main native settlements of the first half of the first millennium BCE, the main acropoleis and Greek and Phoenician colonies.

to restrictive or esoteric practices and others to ancillary practices, such as the storage of food or objects used in these ceremonies (Ferrer 2012). At the same time, the considerable presence of open spaces, where auxiliary structures such as altars, hearths, or pits were located, indicates that the ritual activities carried out in these areas were probably visually accessible to a wide audience (Ferrer 2012).

Material evidence from the acropoleis bears witness to a great variety of ritual practices, ranging from the emphasis on deer hunting at Monte Polizzo (Morris et al. 2002), to metal production at Colle Madore (Vassallo 1999), to the accentuation of the warrior group in the latest levels (sixth century BCE) of Polizzello (De Miro 1988). Despite this considerable diversity, in all of these settings and throughout their occupation, three highly ritualized practices have been repeatedly documented: the cleaning of these spaces, as suggested by the few finds in these places (Ferrer 2012, 394–8), votive deposition, and collective commensality. These three activities do not represent a novelty within the Sicilian ritual tradition; all of them have been documented in communal ritual places located at settlements dated in the precolonial period, for example, in La Muculufa (Holloway et al. 1990); in Madre Chiesa di Gaffe (Castellana 2000) or the first levels of Polizzello (Tanasi 2009).

In sum, the geographical and architectonical features of these places, as well as the successive celebrations carried out in them, make the acropoleis crucial spaces of local interaction inside the settlements. They were meeting points, but also, due to their visibility, they were places of mnemonic reference for all those who lived in or even only visited these centers. The continued execution of communal feastings in these settings converted the acropoleis into arenas where social solidarity was promoted and group identity was forged among all those who participated in these events (Ferrer 2012, 2013). The heterogeneity of the participants, however, their different experiences and social and cultural identifications, also turn the acropoleis into arenas where the various power relations that existed within these communities were built, negotiated, and reified (Ferrer 2012, 2013).

Feasting the community: Drinking and eating on the acropoleis

In the last few years, several archaeological studies conducted from different theoretical and methodological perspectives have argued for the sociocultural importance of feasting practices (among others: Dietler 1990; Gumerman 1997; Hamilakis 1998; Dietler and Hayden 2001; Pauketat et al. 2002; Bray 2003; Halstead and Barrett 2004; Jennings et al. 2005; Swenson 2006; Twiss 2008; Hayden and Villeneuve 2011; Ferrer 2013). All of these studies assume that feasts are a universal phenomenon imbued with a community’s ideology wherein social identities are established and altered. These studies conceive of feasting as a key factor in the negotiation and maintenance of social order as well as in processes of social change. Practices of collective commensality are understood as arenas where both social competition and integration are produced simultaneously. As Dietler (2001, 77) has pointed out, “Feasts conceived sincerely by the participants as harmonious celebrations of community identity are simultaneously arenas for manipulation and the acquisition of prestige, social credit and the various forms of influence […] that social capital entails.”

Most of these studies argue that the power of feasting derives precisely from its extraordinariness, in particular the presence of a larger number of banqueters and a differential consumption of food and drink, both in quantity and quality (Dietler 1990; Gumerman 1997; Dietler and Hayden 2001; Pauketat et al. 2002; Bray 2003; Jennings et al. 2005; Hayden and Villeneuve 2011). This perspective based on exceptionality isolates feasting practices from daily meals. In spite of this usual stress on the exceptionality, in this particular context I assume that the importance of the feast lies precisely in the social and symbolic dimension of food, as well as in the close relationship and the continuity that exists between these colle...