![]()

1 Introduction

Stories and Social Media in Context

This book is about stories that are told in social media contexts. It focuses on stories that are told by everyday tellers about their personal experiences, arguing that these stories are important discursive and social resources that create identities for their tellers and audiences. Storytelling is an interactive process, traces of which can be seen in the conversational formats of social media and are interwoven between online and offline contexts. The range of stories told in social media contexts is wide and diverse. The stories discussed in this book include examples taken from the popular social network site Facebook, and the microblogging site Twitter, alongside stories told in older forms of social media like discussion forums, personal and video-blogs, and stories that are collected in formally curated, community online archives.

Stories are told about many different topics. They include reports of professional activity, like this update on Twitter from the mayor of London, Boris Johnson, who reported on a recent visit to the London Tube renovations,

Incredible amount of work going into improving the Tube. I went to see what happens when part of a line is closed http://bit.ly/hSvpoB

MayorOfLondon: April 14, 2011

and the updates from the British television presenter Amanda Holden, who documented behind the scenes as she got ready to present the talent show, Britain’s Got Talent,

Trying on some of my gorg frocks for BGT live today! Very excited x Amanda_Holden: May 20, 2011.

Social media is also used to document ongoing stories of personal experience from the narrator’s private life, like this Facebook updater who told her Friends that she

is contemplating cycling to the gym, doing Bootcamp & cycling back. Then I have the rest of the day to get ready for the Ball tonight (& have a nap, maybe!)

May 21, 2011 at 07:22.

Four hours later she updated again,

Ah well, cycled to the gym, tick, did Bootcamp, tick, had tea and toast and nice chat with friends, tick. The come out having mentally prepared for the cycle home, to find bike has a flat tyre! So currently waiting for my husband to come and get me and bike!!! (No tick!!)

May 21, 2011 at 10:45

Stories published in social media formats can include deeply personal, emotive topics. In the blogosphere, the blogger Minerva’s most recent post dates from August 2010, where she describes her anxieties about the future after having survived treatment for cancer. She tells her readers,

Already, I am scared stiff and I am still at the computer writing. But it is worth the time to consider the risks of everyday life, to understand how lucky we are that we are able to plan for next year, or even three years after that without having the shadow of the present fog our future. Enjoy the planning, the goal setting and the dreams, but don’t forget to give thanks for our present.

Minerva, August 14, 2010.

As these examples show, stories told in social media can range from seemingly lightweight reports of getting a puncture on a bike, to profoundly significant life events, like the accounts of being diagnosed and treated for terminal illness. Social media cross between private and public contexts, with public documentation of professional activity in Twitter, on the one hand (such as Boris Johnson’s and Amanda Holden’s daily updates), and the semi-private domains of Facebook, on the other. Stories can use words, images, sound, and audiovisual resources, like the videos published in YouTube and the podcasts available from the archives of the oral history project [murmur]. And these examples only begin to hint at the complex variety of stories that continue to proliferate in every form of social media that has been developed thus far.

Ways of studying narrative phenomena are likewise varied. The approach I take in this book is situated in sociolinguistic and discourse-analytic research traditions, but the discussions also touch on concepts that are more familiar to literary-critical narrative theory. The stories selected for discussion in the following chapters are deliberately varied, but are used to address the following key questions:

1. What kinds of stories do people tell in social media formats? What similarities and differences occur in the narrators’ choice of subject matter and storytelling style?

2. How are stories embedded in the multilayered contexts of social media? How do different sites, interactive patterns, offline contexts, and participant groups influence the characteristics of social media stories?

3. What purposes are fulfilled when stories are told in social media? What personal, social, and discourse identities are constructed for narrators and their audiences?

Given the expansive scope entailed by analyzing stories in social media, this introductory chapter defines and provides the context for the key terms and concepts that inform the study as a whole. The chapter begins by setting a sociolinguistic approach to stories in social media against the backdrop of earlier narrative research in digital media. It moves on to consider the storytelling potential of social media in terms of the narrative dimensions set out by Ochs and Capps (2001). Collecting stories in social media presents new challenges and opportunities for narrative analysis, and I review the methods and the data that were used to select the storytelling examples covered in later chapters, ending with an overview of the organization of the book as a whole.

EARLIER WORK ON NARRATIVE IN DIGITAL MEDIA

The need to take account of the everyday storytelling that takes place on the Internet is particularly pressing given the increase in storytelling environments enabled by the advent of social media. The story-like fragments found in social media contexts are often ephemeral, small, located on the margins of other kinds of talk, and fall outside the canon of digital narrative. While they are not necessarily presented as works of fiction, many of the day-to-day accounts of life experience are selective, artistic, reflective, playful, emotive, and sometimes as unreliable as the texts more centrally positioned in digital narratology. Digital narratology examines stories that depend on a computer for their production and display (Harpold 2005). In the early 1990s, critics used the distinctive textual qualities and interactive affordances of hypertext fictions (notably those published by Eastgate, and later archived by the Electronic Literature Organization), interactive fiction, and gaming environments to rework key concepts in narrative theory. The digital narratology of the 1990s was characterized by attempts to document and theorize the then novel artistic forms in terms of their narrative potential. At the same time, it sought to rethink the reader’s relationship with the text through metaphors of agency, immersion, and interaction (Ryan 1991, 2004, 2006; Aarseth 1997; Landow 1997; Hayles 2001).

Work in this field has gone on to scrutinize examples of digital fiction in relation to debates about fictional worlds (Bell 2010), literary competence (Ensslin 2007) and complexity (Ciccoricco 2007), temporality (Montfort 2003), and wider critical practices (Page and Thomas 2011). Digital narratology continues to flourish, but it is limited in three ways. First, it tends to focus on fictional examples of narrative art. Second, interactivity is primarily conceptualized in terms of reader–text relations rather than interaction between human participants. Finally, digital narratology is interested in readings of particular texts, rather than a more fully contextualized approach to narrative production and reception.

Although the more recent examples of narrative criticism found under the umbrella term “digital fiction” (Bell et al. 2010) positions itself against earlier work by applying more systematic models of close reading derived from stylistics and narratology, the legacy of literary-critical narratology remains inherent in the text-immanent focus of the readings typical of the field. Readers are treated as abstract figures mostly projected from the critic’s own interpretation of the text, and there is little attempt to contextualize the practices of narrative production and reception from an empirical standpoint (e.g., documenting the demographic characteristics of actual readers or comparing communities of readers and writers). More seriously, digital narratology appears to treat “fiction” as if it were a transparent, unproblematic term that automatically excludes contemporary genres like blogs, digital storytelling, and life narratives. The literary-critical emphasis of digital narratology has thus resulted in a narrow corpus of texts from which narrative concepts and frameworks are derived, a too simplistic elision of fiction and narrative in digital media, and the need for a greater attention to the contexts of storytelling.

At the same time that foundational work in digital narratology was emerging, research into the wider domain of computer-mediated communication (henceforth CMC) was also being established as a recognized field of inquiry. Like digital narratology, research in CMC developed as an interdisciplinary enterprise. However, in contrast to the literary-critical work of digital narratology, the disciplines that inform CMC have origins in the social sciences and linguistics, including discourse analysis, pragmatics, ethnography, sociology, conversation analysis, and sociolinguistics. CMC research that takes linguistic analysis as its point of entry is focused on the interpretation of textual features found in digital texts but, unlike the individual narrative artifacts interpreted in digital narratology, tends to focus on larger datasets where attention is given to constructing empirically testable research questions that uncover generic rather than text-specific patterns. Examples include tracing the evolution of turn-taking patterns from face-to-face to computer-mediated formats (Harrison 1998), establishing the subcategories of particular genres, like weblogs (Herring and Paolillo 2006), and documenting how norms for online interaction are established (Baym 1995).

Although what Androutsopoulos (2006) describes as the “first wave” of CMC tended to focus on the medium-specific properties of different kinds of CMC (Internet Relay Chat, e-mail, text messages, listserv posts, and “netspeak”), the contextualist principles inherent in the research traditions that inform the study of CMC mean that later work has shifted readily to more user-centered accounts of computer-mediated discourse. This later sociolinguistic work has documented the many and varied ways in which the heterogeneity of discourse found in computer-mediated contexts is not random but may be distributed according to patterns influenced by the constraints of a given genre or the characteristics of the CMC participants (such as their declared age or gender). A user-centered approach to research in CMC has also sought to interpret the pragmatic and social functions of the discourse, for example, in terms of the relational, personal, or group identity work being achieved.

Neither the first nor second wave of research in CMC is limited to the analysis of a particular genre. However, forms of CMC that have come under scrutiny have included examples of personal narratives (McLellan 1997 on illness narratives in discussion forums; Harrison and Barlow 2009 on advice narratives in support groups; Georgakopoulou 2004, 2007 on small stories in e-mail; Eisenlauer and Hoffman 2010 on weblogs). These studies have focused more on the interpretation of the data within the specific online context in question, and less on wider treatments of how narrative genres per se are being reworked in discursive online contexts.1 As such, the rationale for this book proceeds from two points of impetus: the need (1) to broaden digital narratology to include contextualized analyses of everyday storytelling in social media, and (2) to use the discourse-analytic and sociolinguistic work of contemporary CMC to bring close focus to the ways in which narrative genres, and in particular narratives of personal experience, are being reworked in online contexts at the outset of the twenty-first century.

SOCIAL MEDIA

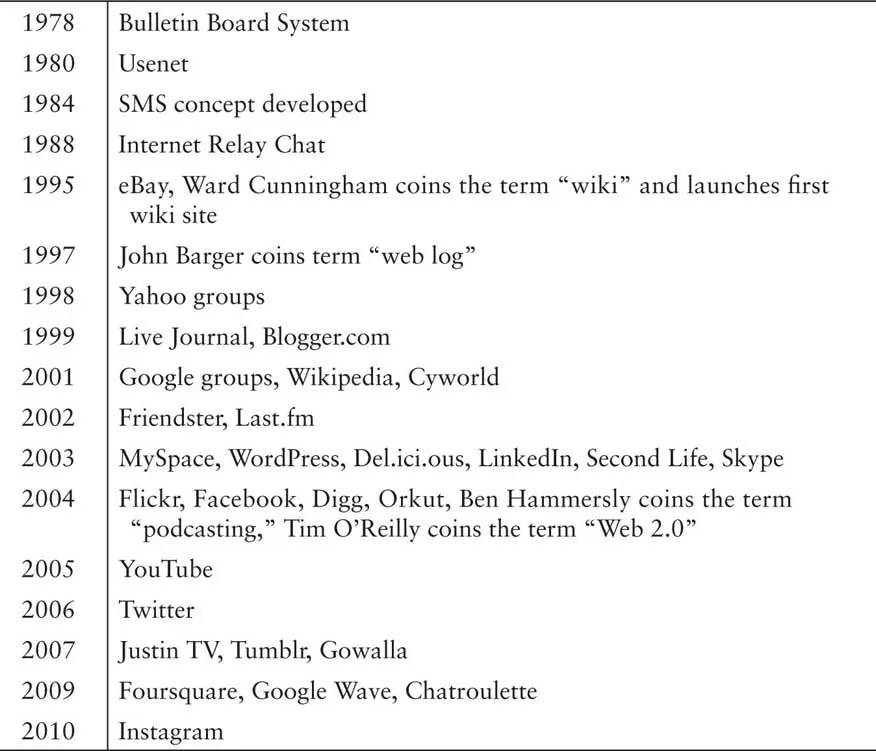

I use the term social media to refer to Internet-based applications that promote social interaction between participants. Examples of social media include (but are not limited to) discussion forums, blogs, wikis, podcasting, social network sites, video sharing, and microblogging. Social media is often distinguished from forms of mass media, where mass media is presented as a one-to-many broadcasting mechanism. In contrast, social media delivers content via a network of participants where the content can be published by anyone but is still distributed across potentially largescale audiences. Social media often refers to the range of technologies that began to be developed in the latter years of the 1990s and became mainstream Internet activities in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The chronological context of social media genres is set out in the timeline in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Timeline of web genres and terms.

The timeline in Figure 1.1 tells a certain story about the development of social media, which moves toward increasingly interactive forms of dialogue. The dialogic potential of social media is present in earlier forms of CMC. The e-mail lists, bulletin boards, and text messages of the 1980s might be seen as precursors to the participatory culture (Jenkins 2006) that characterizes twenty-first century Internet behavior. But the mid-1990s saw a decisive shift in the way that social media enabled interaction between participants, and placed that interaction in public rather than private or semi-private contexts. Blogs and wikis extended the range of CMC’s interactive possibilities, with blogs allowing individual writers to connect to other bloggers (through blog rolls, links, comments) and wikis fostering collective contributions to a single enterprise (Myers 2010). These became mainstream examples of Internet use when sites like Live Journal, Blogger, and later WordPress made it easier than ever for contributors to publish reports and opinions, and Wikipedia was launched in 2001. The years 2003–2006 saw a rapid expansion of social network sites (LinkedIn, Orkut, MySpace, Flickr, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter) that reframed the dialogic links between participants as a network, increasing the number, visibility, and reach of an individual’s connections with others in online spaces. More recent developments, like the Instagram photo-sharing application for the iPhone, Gowalla, and FourSquare, illustrate the extent to which social media networks have become untethered from static computer terminals. Social media interactions are interwoven increasingly with daily experience, through the use of mobile technologies like smart phones.

The scale on which social media has been adopted needs to be understood in the wider history of the Internet. The mid-1990s saw several technological developments that would enable the later social media genres to gain popularity. In 1993, Mosaic was the first popular web browser to make the web available to a wider audience. MP3 file formats became publically available from late 1994, Real Player was launched in April 1995, and Macromedia’s Flash Software was released as a browser plug-in from 1996. These technological developments facilitated digital animation and audio resources that could be created and shared with relative ease, transforming the Internet from a text-based medium to the richly varied multimodality that is now familiar. By 1997, commercial standards for wi-fi had been agreed, and 1996 saw the first smart phone (Nokia 9000 communicator). Access to the Internet was no longer restricted to static computer terminals connected to wired power supplies. With increased possibilities for access, social media could be produced and consumed in a greater range of locations and at any point in time. By 2007, 70 million blogs were indexed by Technorati. Two years later, 13 million articles had been posted on Wikipedia. In 2010, the major social network sites boast millions of members each. There are 145 million registered members on Twitter, 500 million active members on Facebook, and YouTube boasts over 2 billion daily views. That said, sites vary in the kinds of demographic groups that use them regularly and not all sites have maintained the same growth. For example, in the United States, the uptake of blogging has increased for those above thirty-four years of age, but halved for teenagers (Kopytoff 2011), and geographically specific sites like the British social network site Bebo soon gave way to the globalized adoption of Facebook.

Social media is more or less synonymous with what O’Reilly (2005) dubbed Web 2.0 technologies. Although the descriptor Web 2.0 is still current, social media emphasizes the social aspects of the web genres in question, particularly the communicative interaction between participants and the implications this might have for macro-social issues such as personal or group identity. By way of contrast, “Web 2.0” was coined within a specific commercial context (Marwick 2010) and has particular business and technical applications that are less of interest to my concerns...