![]()

1

The Sites of the Paris Region and Northern France

Abbeville, Somme

Museum site.

www.archéologie-aerienne.culture.gouv.fr

Musée Boucher De Perthes

Rue Gontier Patin

80100 Abbeville

| Hours: | 2 May–30 September | 2–6 p.m. Closed Tuesday |

| 1 October–30 April | Wednesday, Friday, Saturday only |

This museum is dedicated to two great men. Its name recalls one of the most important founders of prehistory, the Abbeville customs officer, Jacques Boucher de Perthes (1788–1868), who began collecting what we now call Palaeolithic tool axes in the gravel pits of the Somme, and recognized that, as the new geology indicated, objects found in ‘antediluvian’, that is very old, deposits must be as old themselves. Further, these primitive tools were contemporaneous with his finds of elephant and rhinoceros bones, so man must have been living in a long distant past. It was a shattering combination of logic and evidence. In 1859, he received the recognition he deserved, initially from British scientists who came, saw – and photographed – hand axes in situ and were convinced.

The museum also commemorates the work of Roger Agache. His work as an aerial photographer revolutionized attitudes towards the potential of aerial photography as investigative archaeology. Perhaps his greatest work was demonstrating, at the beginning of the 1970s, that the Somme region had been covered with villas during the Roman period, many of them very large and imposing. He was able to bring out the significance of their discovery through his follow-up mapping, marking both these and their late Iron Age predecessors, pointing to the links between the two eras and the role played by the Roman roads (also revealed in his photographs), giving depth and raising new questions concerning the relationship between the villas, new cities and long-distance military markets. Equally his work has helped push research in new directions through his photographs of known sites, showing unsuspected ditches and occupation (see LA CHAUSSEE TIRANCOURT). It is not simply that Agache has inspired aerial photographers everywhere, he has also consistently argued that archaeology should communicate, not just with other specialists, but with all people.

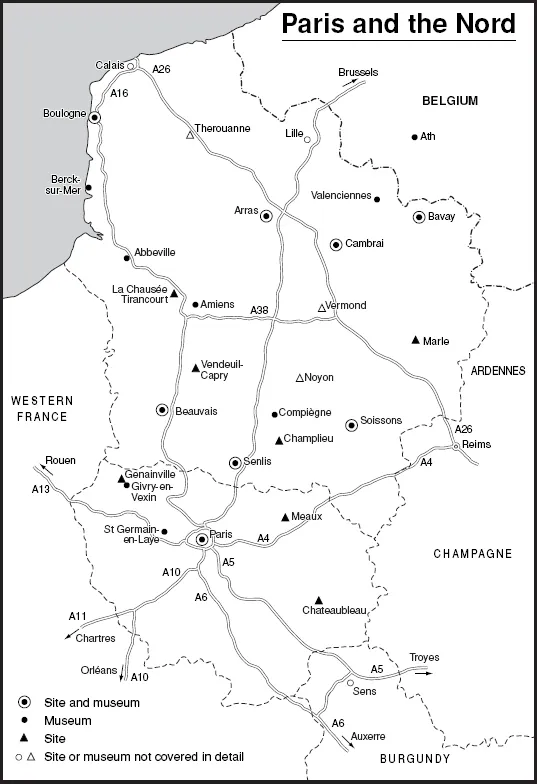

Figure 5 Regional Map: Paris and the Nord

The Collection

Agache’s photographs of the late Iron Age and Gallo-Roman sites are featured in the entrance in a display roundel. Further photographs in the galleries show how his pictures demonstrate not only his superb skill in revealing hidden evidence but also a deep aesthetic sense of the environment.

Displays are periodically rotated between the public galleries and the reserve collection. They include older material such as the miniature flat figures of the late La Tène period suggesting phallic images, a form of male fertility imagery that may suggest Cernunnos, though he is more usually indicated by the addition of stag horns. While there is no evidence that there was any significant settlement at Abbeville during the Gallo-Roman period, isolated finds have been made here, including bronze jugs of high quality, one with a pair of finely wrought hands at the base of the handle. There is also an excellent lamp standard. More recent Gallo-Roman finds from outside Abbeville include an iron grill stand and a wine ladle, the latter found at Béhen, following the site’s discovery in one of Agache’s aerial surveys. Merovingian burials have provided typical examples of buckles and swords.

Amiens, Somme

Museum site.

Amiens is frustrating. Well excavated for a number of years, yet there is nothing Gallo-Roman for the visitor to see outside the regional museum. Since the Second World War, local and regional governments have encouraged investigation – though not preservation – and the municipal archaeology service continues the meticulous work started by Vasselle, followed by Massy and Bayard. More has been discovered about the layout and development of the capital of the Ambiani tribe than about most other civitas capitals in northern France.

Samarabriva (‘Samara crossing’) was laid out in a classic grid pattern, on the southern bank of the Samara (Somme) river. No evidence of Gallic settlement has been found, though it is likely that there was a road here, as the gravel terraces would have made the naturally marshy river bed easier to cross. Possibly Julius Caesar identified this as the key point to control the region, but the enigmatic evidence from LA CHAUSSEE TIRANCOURT suggests that military surveillance in the area was done from there, though there are hints of a military presence on the site of Samarabriva from c. 20 BC, perhaps linked to the construction of the major Lyon–Boulogne road.

In the last years of Augustus’ reign city streets were laid out in rectangular blocks, aligned to the slopes of the valley, leaving the road cutting through them at an angle. The new town developed slowly and the grid was changed to squares (385 Roman feet/160m) in the 50s, when it began to grow more rapidly and the insulae to fill up. The buildings were still largely wood and cob, but stone foundations were more widely adopted under the Flavians; the forum was finally completed in the 70s/80s, unusually taking up two insulae linking the macellum, or commercial market, to the political and business centre in an exceptionally long building. No temple has been identified here or anywhere else in the town.

Evidence of a massive fire towards the end of the first century has been found at many sites in Amiens, but the town was rapidly rebuilt on a grander scale with more stone and better drains. There was a large public baths system with hot and cold swimming pools and an aqueduct to supply it with running water (though only fragments of the latter have been found and its course is unknown). An amphitheatre was constructed, unusually sited at the centre of the town, flush against the forum. Perhaps, as Massy and Bayard suggested, the city council found land deserted and cheap after the fire. Excavating the foundations for the late nineteenth-century Hôtel de Ville revealed the defining oval and foundation walls. Fragments of rich houses that occupied other central insulae have been found decorated with mosaics and wall paintings (none providing very extensive remains) and further building took place, even in the marshy northern areas. Once again major fire struck. Extensive fire levels dated to the 170s were again followed by reconstruction. During the early third century new building still took place but on a smaller scale. By the 240s Samarabriva, like so many other cities in Gaul, was beginning to show signs of contraction. There were renewed fires. Rubbish filled some areas, some insulae reverted to gardens and cemeteries began to encroach on sites previously occupied by the living. The barbarian invasions of the late third century were only the culmination of a declining ability to maintain classical life in Amiens.

Samarabriva was a genuine crossroads site: a major north–south road artery and an important east–west river route. In addition tributary rivers (the Avre and Selle were only the nearest) and roads made Samarabriva a good focal point for the regional economy, which was of course agricultural. Agache’s brilliant aerial photography (see ABBEVILLE) revealed the density of villa estates across the Picardy plains. Meat, leather and bones would have helped stimulate local business, but wheat production must have played the key role. The army was a significant market and while much wheat would have gone east to the Rhineland frontier, some will have gone via Samarabriva to the Channel and either along the coast to Germany or more frequently to Britain. Equally, Samarabriva not only consumed the export goods from elsewhere, such as pottery, glass and wine, but must have been responsible for sending at least some of them down the Somme to St Valéry and to Britain; the discovery of both lead and tin ingots suggests that this also was a route for returning imports. There are hints, too, that it was a military transit point where troops perhaps rested when being moved from Britain to the Rhineland and back and that the surges in growth can be linked to the Claudian invasion and its follow-up (AD 43–70), the construction of Hadrian’s Wall (120s), and the Severan campaigns in Scotland (early 200s).

It is also probable that what prosperity the late Roman ‘city’ had in the fourth century was based on the continuing military role of Samarabriva Ambianorum as a continuing link between Britain and the Rhine, as part of the defences against Saxon raiders, and for local control, for example in overseeing barbarians (e.g. Sarmatians) drafted in as settler-soldiers. It must have helped keep the regional villa economy going for a time as well.

Ambiani – as it was increasingly called – had an irregular rampart enclosing about 20ha. This was made with the usual hard-headed disdain for the buildings and funeral monuments of the earlier city. As at BAVAY, the forum walls were used to provide a basic structure and the amphitheatre became the core buttress. One part of the forum became a metal workshop, perhaps the shield and sword fabrica Ambiensis referred to in the Notitia Dignitatum. Written sources also suggest a Christian presence: an oratory dedicated to St Martin (c. 316–397) by one of the gates is mentioned by Gregory of Tours and the story of his conscientious objection here may well be true – he could have been part of the local garrison. However, no archaeological evidence has been found of any churches. During the fifth century, it is impossible to say at what point Ambiani was permanently lost to the empire – the 450s? the 460s? – not simply because the written sources do not tell us, but because whether it was ruled by a local Roman warlord or a Frankish king must have been almost irrelevant to the peasants who worked the land and who no longer had any use for the city.

Musée De Picardie

48 rue de la République

80000 Amiens

| Hours: | 10a.m.–12.30p.m., 2–6p.m. Closed Monday |

Renovation has transformed the basement of this grandiose Victorian building into a modern, tasteful display area. Following collections of ancient Egyptian and Greek – especially Corinthian – material, there are three galleries devoted to the Gallo-Roman period. Here is the visible evidence not only of Samarabriva and Ambiani, but also of other sites in Picardy, most important perhaps being Ribemont-sur-Ancre (see THE ROMANO-CELTIC SANCTUARY).

The most striking portrayal of Ribemont is the re-created headless burial, with the original skeletal remains, bent swords and other weapons. A case shows the wide range of Gallic weaponry found surrounding the sanctuary. The high quality of the decorative stone sculpture on the later Roman temple is hinted at by the expressiveness of the faces.

The earliest material from Amiens is suggestive of a military presence. Arretine ware, sigillata from Arezzo in Italy, could indicate army use, and a dagger scabbard, found in the same deposit, has been identified as typical of an Augustan auxiliary. Attractive British enamelled fibulae confirm the cross-Channel connection. There were also travellers and tourists. Someone came to Samarabriva with his or her souvenir cup commemorating Hadrian’s Wall. It has a list of names enamelled round its rim: they record a number of western forts from MIAE (Bowness) to BANNA (Birdoswald). Perhaps a soldier in transit from the Wall to the German frontier was quartered here? Perhaps a retired man chose to settle in Samarabriva? The elegant carved bone officer statuette, which may have been a soldier’s offering, was found at the fanum on the Somme oppidum of L’Etoile.

The Amiens area has no good clay and little local production. The creamy terracotta moulded statuettes, produced in central France, are mostly simple and cheap representations of fertility and plenty, either classical Venuses or Gallic seated mother figures in their basket chairs, but Amiens has some splendid zoomorphic designs, especially a seated stag. Glass was imported as well, some as expensive tableware, some for perfumes and medicines and some as appropriate goods to accompany a person’s burial. The collection, largely from the cemeteries, is a fine one, the best being the chalice from the Rhineland, with its blue-and-white snake décor.

There are only hints at the appearance of Samarabriva, for example the beautifully decorated column drums with hares, birds and figures surrounded by foliage, but the evidence found so far suggests that the larger houses were unimpressive. Dull geometric mosaics are representative of the small number found. Finds of painted plaster decorated with candelabra and griffins, discovered in the rue de Jacobins domus excavation, are better than many, but pale beside the sophistication of the section of wall-painting brought back from the Boscoreale villa (Italy). The broken oscillum, a marble plaque hung in a house or on a garden tree, is of high quality and shows Pan playing his pipes before a rural altar; it must have been imported. The small bronzes are also interesting. There is a strange cross-legged god whose right ear is that of an animal (see also BESANCON). Is the ear a stag’s, in which case it might be a personification of Cernunnos, or is it a bull’s, identified possibly with Jupiter, symbolizing virility? Another strange statuette is dedicated to the worship of Jupiter–Sabazius. ...