P

paenula (L) A heavy Roman WOOLLEN CAPE, often HOODED, of uncertain origin: the earliest literary evidence is Plautus (Mostellaria 4.3.991, c. 200 BC). It may be connected with the Greek phainole, but is most likely to have come via south Italy or Sicily: perhaps a model for the GALLIC cape, not vice versa. Its precise shape and pattern has been disputed: it may have varied in design over time, but was probably made from a semi-circular piece of material, the two straight edges brought together in front and sewn (Fig. 31). If so, the garment was put on over the head (indutus) not wrapped (amictus), but the two edges might have been FASTENED by hooks-and-eyes or buttons/ toggles and loops. Length varied, but early-mid imperial art often shows it falling to the knees or mid-calf. It could be worn as an all-enveloping garment that covered the arms, but as only a small section of the front was usually joined, one or both front portions could be thrown back to give more freedom of movement. The paenula often – but not invariably – had a hood, either integral or made separately and attached: Pliny describes bindweed leaves as shaped like its hood (capitium NH 24.88.138), so it was probably folded down on the back. The hood is rarely represented over the head in art, instead either hanging down the back, or absent.

The paenula was associated with bad weather, especially rain, and travelling. It was worn by various kinds of people – including women: labourers wore workaday versions and SOLDIERS on the northern frontiers wore them both on- and off-duty. Soldiers on Trajan’s column wear paenulae, as does the emperor himself. The paenula was also commonly worn by ordinary citizens in crowd scenes of ‘the people’ on state reliefs (Anaglypha Traiani, Arch of Constantine). In the early empire the paenula was not considered APPROPRIATE attire for upper-class Romans – except when travelling – but clearly there were superior versions: e.g. Canusian of the best quality Apulian wool, those worn as FASHION items in Rome, the paenula gausapina of fine WHITE wool with shaggy NAP, and Caligula’s paenula decorated with EMBROIDERED pictures and GEMS. Although ordinary paenulae were probably the natural COLOURS of wool, or DYED a dark colour, they could be white or RED – mosaics represent various colours – even of LEATHER (scortea, Martial, 14.130), SKINS or FUR. Worn over a tunic, not over a toga, paenulae gradually came to replace the toga as the official dress of Roman citizens by the fourth century AD: an edict of 382 (Code of Theodosius 14.10.1.2) even decreed that it should be worn by SENATORS. The paenula also eventually became a CHRISTIAN church vestment, the correct dress for bishops from the time of Constantine. Casula is another name for late imperial paenulae, which evolved into the chasuble.

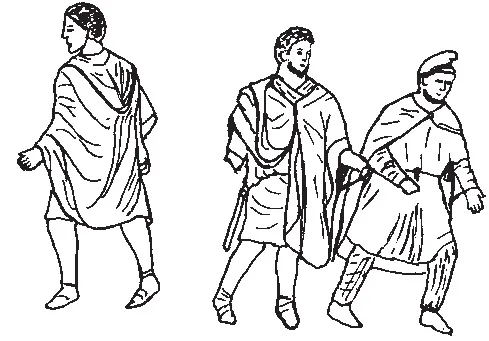

Figure 31 Two Roman SOLDIERS and a BARBARIAN prisoner from the Arch of Septimius Severus, Rome. Both soldiers wear the PAENULA – seen from the front and back, with the HOOD – the prisoner a TUNIC over long loose TROUSERS, a CLOAK fastened with a BROOCH, and a hat which characterizes him as from the EAST.

Pliny, NH 8.73.190; Martial, 2.57.4, 5.26.1, 14.145, 14.130; Suetonius, Caligula 52; Kolb (1973: 69–167).

palindoriai (G) Mended SHOES.

Plato Comicus, 164; Pollux, 6.164.

palla (L) Female equivalent of the pallium, especially worn outdoors (Fig. 27). It covered the body from shoulder to knees – it might fall to the ankles: it is usually represented as a voluminous garment – i.e. expensive – elegantly DRAPED in a number of different ways. It could be worn over the head as a VEIL, draped diagonally round the body like a toga, over both shoulders like a shawl, or even round the hips (Ara Pacis Augustae processional friezes). As it was not fastened at all, it relied on DRAPING, and is often shown being held in one hand, and/or with one hand completely hidden inside. This made it suitable for leisured women of the upper classes, but not for any practical activity. Nonius says that respectable women and MATRONS should not appear in public without it; Horace complains that the all-enveloping stola and palla show only MATRONS’ faces (537–8M; Satires 1.2.94–9). The palla – probably usually made of WOOL, lighter summer versions of LINEN, COTTON or SILK – could be any COLOUR at all, except from 215–195 BC, when the Lex Oppia forbade PURPLE. In the early empire it was usually plain, with at most a contrasting BORDER, but in the third and fourth centuries AD could be decorated with PATTERNED roundels, and later still might have more complex decoration. A smaller version, the palliola, was also available, especially later.

Varro, Latin Language 5.131; Davies (2005: 121–30).

palliatus (L) Wearing a pallium, so identifying as Greek rather than Roman. Plautus already uses this as a sign of general Greekness, and is followed by later writers. Palliatus is often used as a foil for togatus: thus Latin comedy adapted from Greek New Comedy was called fabula palliata, to distinguish it from the home-grown fabula togata. Palliatus is also used by modern art historians to designate statues of men wearing the pallium (cf. togatus, NUDE or ARMOURED).

Cicero, Philippic 5.5.14.

pallium (L) The Greek himation in a Roman context: a wrapped rectangular mantle worn in a variety of different ways, alone by PHILOSOPHERS, but usually with a TUNIC underneath. For the Romans it was the quintessence of Greek dress, so they were very careful about wearing it: never when a toga was APPROPRIATE. Thus Scipio Africanus was criticized for wearing the pallium with SANDALS at the gymnasium in Sicily; Cicero, defending Rabirius, has to excuse his wearing it in Alexandria; Tiberius is wrong to wear pallium and sandals in exile on Rhodes; Hadrian was careful to wear the pallium to banquets only outside Italy. In the second century AD, the pallium was associated with intellectual activities in general – worn by philosophers, teachers, doctors, poets and sophists, i.e. anyone who claimed to be cultured, many from Greek parts of the empire anyway: these associations made it the appropriate dress for CHRISTIANS in preference to the toga. It seems the pallium was little worn in the north-west PROVINCES (Wild 1985: 385), but is the garment most often worn by saints and patriarchs in early Christian art.

Suetonius, Augustus 98.3, Tiberius 13.1; Livy, 29.19.12; Cicero, For Rabirius 9.27; SHA, Hadrian 22.4–5. Tartallian, De Pallio.

palmata (tunica) (L) The TUNIC worn by the general at his TRIUMPH, possibly decorated with palm motifs, palmettes.

Livy, 10.7.9.; abola.

PALMYRA The large corpus of funerary sculpture from this Syrian city allows us to deduce many of the intricacies of Palmyrene dress (Figs 22, 32). While some Greco-Roman influence exerted itself on Palmyra’s elite – especially women – there was a distinct eastern tradition in fashionable looks. Men tended to wear either an ample full-length TUNIC with a length of rolled cloth knotted around the hips, or an Iranian style side-vented tunic with long SLEEVES over a pair of TROUSERS tucked into BOOTS – like PERSIAN anaxarides, but fuller, looser and apparently SILK – particularly as a riding or HUNTING habit, with leggings or chaps to protect the fine fabric of the trousers. Palmyrene noblemen might wear a himation, pallium or chlamys over this. Chaps of silk or LINEN could be worn indoors too. Palmyrene women wore full-length gowns, long sleeved with ornamented cuffs, under a silk or linen chitōn, fastened Greek style, or on one shoulder only with a large and conspicuous BROOCH. Most women appear to have worn fabric turbans, often draped with jewelled ornaments and pendants, under long light silk VEILS. The visual richness of Palmyrene dress is obvious: couched EMBROIDERY, BROCADES, WOVEN PATTERNS, BEADING, APPLIQUÉD strips of braid and fine spun silk and linen gave the clothes of the nobles of Palmyra a distinctly opulent look.

Goldman (1994: 163–81).

paludamentum (L) The MILITARY CLOAK worn by Roman generals and emperors – e.g. on Trajan’s column and numerous CUIRASSED statues of emperors – fastened by a BROOCH on the right shoulder. Similar to the chlamys, it was long – to mid-calf – possibly with a curved lower edge, DYED SCARLET or PURPLE, or BLEACHED white. It was worn by commanders when setting out for war, and SYMBOLIZED both legitimate authority and honour – Antony ordered that Brutus be cremated in his. According to Florus (1.5.6) it was introduced into Rome very early.

Figure 32 Reclining man from a PALMYRENE funerary relief in Philadelphia. He wears a TUNIC with long SLEEVES over long loose TROUSERS: both garments are DECORATED with BANDS and BORDERS.

Nonius, 864L; Pliny, NH 22.3.3; Livy, 41.10.5, 45.39.11; SHA Marcus Aurelius 14.1; Harlow (2005: 143–53).

PANNONIAN DRESS See NORICUM AND PANNONIA, (Fig. 29) for pilleus Pannonicus see pilleus.

pannus (L) Cloth or FABRIC; sometimes, rags.

Martial, 2.46.9; Barber (1991: 273).

panus (L) Thread wound on a bobbin or pin-beater, see pēnē.

Nonius, 217L.

paragauda/is (L) With WOVEN or EMBROIDERED decorative BANDS, used of LATE ANTIQUE clothing, especially tunics.

SHA Aurelian 46.6, Claudius 17.6; Code of Theodosius 10.21.1.

parairēma (G) Side SELVAGE, cf. asma.

Thucydides, 4.48; Barber (1991: 272).

parakymatios (G) ‘Sea-wave’ PATTERN, probably a BORDER. Attested only from BRAURON – for the generally highly decorated chitōniskos – but quite commonly seen in artistic representations of various types of dress (Fig. 39).

Miller (1997: 177); Cleland (2005b: 15, 62–3, 122); IG II2 1514.46.

paralourges (G) With a PURPLE border; see halourgos, parhyphēs.

IG II2 1515.26, 69.

parapoikilos (G) BORDERED with PATTERNS (Figs 1, 39).

IG II2 1522.12; 1523.19: Miller (1997: 177).

PARASOLS Small canopies used as protection against the sun in Egypt, Persia and elsewhere in antiquity: often an emblem of rank. Old Kingdom EGYPTIAN tomb paintings depict dignitaries shaded by a parasol held by a bearer; this remained a signifier of rank throughout Egyptian history. In the New Kingdom tomb of Huy, a travelling Ethiopian princess has one fixed to a tall STAFF rising from the centre of her chariot, like those in the chariots of Assyrian monarchs. Discoveries at Nineveh show parasols – edged with TASSELS, and usually with a flower or other ornament on top – carried over the king in times of peace and war. On later bas-reliefs, a long piece of LINEN or SILK, falling from one side like a curtain, appears to screen the king completely from the sun. The parasol was reserved exclusively for the monarch and is never represented as borne over any other person. The PERSIAN king and his satraps were often portrayed (e.g....