The ever-changing and ephemeral nature of emotions has led many to believe that it’s impossible to consistently trigger emotional responses through design. Over the last three decades, research that examines the relationship between design and emotion has grown steadily. This research has provided new ways to visualize the basic dimensions of emotion, allowing for the creation of models that can help us understand and design for emotional responses. In the upcoming chapters, we’ll be describing a number of ways to model and understand how products affect us on different emotional levels.

By the end of this book, you should have a basic understanding of emotion and why users’ experiences affect the way they make decisions, become motivated (or unmotivated), behave, and perceive personality. You’ll learn when to balance users’ emotions through design and you’ll be able to predict the emotional level at which you should focus your design efforts. Finally, we’ll tie it all together with the A.C.T. framework, along with a set of guidelines for designing more emotional experiences.

Useful, Usable and Desirable

When Trevor was a teenager, he would go to the traveling car shows that would come to the convention center near where he grew up. The shows would feature famous cars from movies and television shows, like the General Lee from the Dukes of Hazzard or the Batmobile from the first Batman movie. Occasionally, they would also have what are called “concept cars.” Concept cars aren’t intended for mass production. Instead, their goal is to showcase new design directions and gauge public reaction to new styling and technology.

Trevor remembers strolling through one of the shows and being entranced with the highlights, sleek lines and gleaming chrome that surrounded him. One vehicle caught his eye, mainly because it had gullwing doors like the car in the Back to the Future movies. He remembers thinking how “cool” it would be to have a car with doors like that, and saying as much to the attendant, seated nearby.

Looking over at him, the attendant asked, “You like this car?” Trevor nodded in the affirmative. “Well,” he said, “don’t get too excited. It’s not like it moves or anything.” “Do you mean,” Trevor asked in slight shock, “that it has no engine?” Standing slowly, the attendant walked over to the car and put his hand on the door. The windows were tinted, making it almost impossible to see any detail inside. Opening the door to reveal an interior with a very basic steering column and no dash controls, he exhaled deeply and said, “Doesn’t really matter how good it looks, if it doesn’t move.”

Fig. 1.1 Time Machine in the Back to the Future Films

Creative Commons

Designers are faced with many (often conflicting) considerations when designing interactive products and services. For a concept car, the most important require-ment is the appearance. From a business standpoint, the concept car needs to be aesthetically pleasing in order to attract public interest. From a viewer or “user” standpoint, the fact that the concept car is beautiful triggers pleasure and creates attraction. In a different context, a need, other than attraction, might be a higher priority for either the business or the users. In a production vehicle, for example, the most important needs would be functionality and usability, rather than appear-ance and desirability.

Designers are faced with many considerations when designing interactive products and services.

Liz Sanders described three categories of product requirements: useful, usable, and desirable (Sanders, 1992). These three categories are intended as a blanket description, covering all the aspects of users’ emotional experiences with products.

Useful: Performs the tasks it was designed for

Usable: Easy to use and interact with

Desirable: Provides feelings of pleasure and creates attraction

To satisfy the goals of your clients (i.e., “the business”) and the needs of their customers (i.e., “the users”), your design must be useful. In other words, it must perform the task it was designed for. It must also be usable, or easy to understand and interact with in a predictable and reliable manner. Usability has become a basic business requirement as well as a user expectation. Finally, in order to attract users, your design must also be desirable. For many types of products, the pleasure provided by beauty has become an expected part of the experience during purchasing, ownership and use.

Sometimes, a product can be immensely useful, but because it’s a new discovery or a new category of products, it’s not yet very usable or aesthetically pleasing. The first computers, for example, were bulky terminals that came with command-line interfaces. As the age of a category of products increases, competitors enter the market with products that offer the same functions. Simple functionality becomes the norm (van Geel, 2011).

When the functional quality of a product increases, usability and aesthetics take on greater importance. As the computer industry and the technology matured, usability and desirability became important differentiators. Today, we have beautiful graphic user interfaces on screens that allow objects to be moved around intuitively via touch on elegantly thin devices. In today’s competitive environment, products that neglect aesthetics and usability often fail to attract the attention of demanding consumers. This applies not only to physical products, but also to websites, software and other digital products as well.

Designers must balance the goals of the business and the needs of the user with the constraints imposed by the technology.

Prioritizing Emotional Needs

When it comes to most products, websites, and applications, our emotional needs are complex and multilayered. We want our products to work while also being easy to use. Of course, it doesn’t hurt if they also look and feel good. Over time, our emotional responses to these criteria can determine whether a product becomes a beloved tool, or a part of the day you simply put up with.

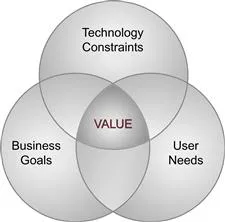

As designers, we must learn to identify the emotional considerations that are most important for the context of use. From there, we can prioritize these considera-tions by examining how each affects our ability to fulfill important business goals and satisfy crucial user needs. Designers must balance the goals of the business and the needs of the user with the constraints imposed by the technology.

Fig. 1.2 Balancing User Needs With Business Goals and Technology Constraints

© Trevor van Gorp

Some of the most successful products have been embraced because they’ve managed to satisfy the emotional needs that were most important for their context of use. Because the use context for every product is different, your solution may need to focus more on some areas than others. As we saw in the example of the concept car, some things really only need to focus on being beautiful. The car with no dashboard controls and no engine accomplishes its purpose in the convention center: to show off new styling and generate excitement. But, it’s not much use outside on the street.

With a different product, in a different context of use, desirability alone might not suffice. Aesthetics may satisfy users’ simple need for pleasure, but providing aesthetics alone won’t supply a usable or useful product. On its own, the concept car, for example, doesn’t fulfill the average user’s needs for a functional commuting vehicle. It won’t actually take you anywhere and if it did, there would be no way to safely control the necessary functions.

Aesthetics alone won’t supply a usable or useful product.

Emotion, Personality and Meaning

So why should you design for emotion? The short answer is that emotion is an overriding influence in our daily lives (Damasio, 1994). It constitutes our experiences and colors our realities. Emotion dominates decision making, commands attention and enhances some memories, while minimizing others (Reeves & Nass, 1998).

The emotions we feel allow us to assign meanings to the people and things that we experience in life. Most of the time, pleasure means “good” and pain means “bad.” When we use products, websites and software applications, we experience complex social and emotional responses that are no different from the responses we experience when we interact with real people in the real world (Desmet, 2002).

When we use products, we experience emotional responses that are no different from the responses we experience with real people.

Over time, the emotional expressions that we perceive in both people and things can come to be seen as “personality traits” (van Gorp, 2006). We perceive personality in the things in our environment and then form relationships with those things based on the personalities we’ve given them (Reeves & Nass, 1998). As Donald Norman put it, “everything has a personality, everything sends an emotional signal. Even when this was not the intention of the designer, the people who view … infer personalities and experience emotions. … Horrible personalities instill horrid emotional states in their users, us...