![]()

1 | Wetland Definitions and Concepts for Identification and Delineation |

INTRODUCTION

The term “wetland” has no single, scientific, universal meaning as it has been applied by scientists from different fields of study, resource agencies with varied interests, conservation organizations, and others to describe land that is wetter than dryland. Since the practices of wetland identification and delineation as well as classification are grounded on how “wetland” is defined, this book begins with a discussion of definitions and then addresses some key concepts in applying the definition on the ground. The latter discussion focuses on applications in the United States since many laws are in place that require on-site identification of wetlands and delineation of their boundaries, and as a result, much thought has been given to the topic since the laws regulate use of private property.

DEFINITIONS

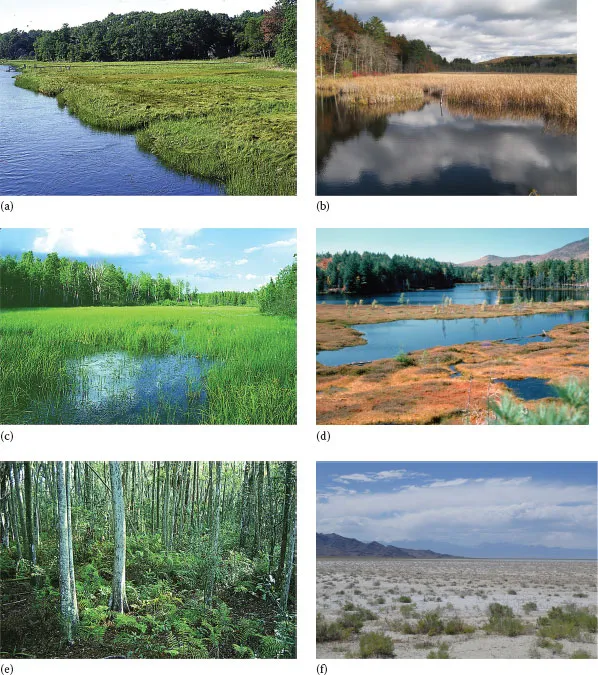

Wetland is a generic term used to define the universe of wet habitats including marshes, swamps, bogs, fens, and seasonally waterlogged areas. Wetlands are environments subject to permanent or periodic inundation or prolonged soil saturation sufficient for the establishment of hydrophytes* and/or the development of hydric soils or substrates† unless environmental conditions are such that they prevent them from forming. These are the places (e.g., landforms) where a recurrent excess of water imposes controlling influences on all biota (plants, animals, and microbes)—this may be a seasonal and more predictive occurrence or an episodic one that is less predictable. Given the regional differences in hydrologic regimes, climate, soil-forming processes, and geomorphologic settings, a vast assemblage of wetland plant communities and hydric soil types have evolved worldwide. Numerous terms have been applied to individual wetlands because of these differences. Some common wetland types in North America include salt marsh, freshwater marsh, tidal marsh, alkali marsh, fen, wet meadow, wet prairie, alkali meadow, shrub swamp, wooded swamp, bog, muskeg, wet tundra, pocosin, mire, pothole, playa, salina, salt flat, tidal flat, vernal pool, bottomland hardwood swamp, river bottom, lowland, mangrove forest, and floodplain swamp (Figure 1.1). Although commonly used, many of these terms do not have universally accepted definitions and may mean different things to different people (e.g., Locky et al., 2005).

Within regions, wetlands naturally form in places on the landscape where surface water periodically collects for some time and/or where groundwater discharges, at least seasonally, sufficient to create waterlogged soils. Common wetland landforms include (1) depressions surrounded by upland and with or without a drainage stream, (2) relatively flat low-lying areas (floodplains) along major waterbodies (e.g., rivers, lakes, and estuaries) usually with fluctuating water levels, (3) shallow water of protected (low-energy) embayments and slow-flowing channels, (4) broad flat areas lacking drainage outlets (e.g., interstream divides), (5) vast expanses of arctic and subarctic lowlands where a permafrost layer occurs near the surface (muskegs), (6) sloping terrain below the sites of groundwater discharge (e.g., springs, seeps, toes of slopes, and drainageways), (7) slopes below melting snowbeds and glaciers, and (8) flat or sloping areas adjacent to bogs and subject to paludification processes in regions with cold, wet climates (see Chapter 2 for details). While most wetlands tend to develop in the areas mentioned earlier, some wetlands form on steep slopes.

FIGURE 1.1 Some examples of common wetland types in the United States: (a) tidal salt marsh, (b) freshwater marsh, (c) fen or wet meadow, (d) shrub bog (Courtesy of Bill Zinni), (e) southern forested wetland, and (f) inland salt flat (Courtesy of Lindsey Lefebvre).

Some people have said that wetland is a euphemism for “swamp” that has evoked negative feelings due to its usage in literature and everyday speech (National Research Council, 1995). If this is true, it is likely an unintentional euphemism, since it is clear that the term “wetland” is simply a combination of two words, “wet” and “land,” that simply describes the overall condition of the land. Such land has water present at or near the surface for significant periods that affect land use. It may be wet too long to grow most crops without some artificial drainage or long enough to pose significant constraints on construction activities (e.g., cannot build without filling and/or draining). The term “wetland” has been in use for some time. Shaler (1890) referred to “the wet lands of the Old World” when comparing the significance of sphagnum growth in the United States to Europe. The common early usage of “wetland” is further witnessed by Dachnowski’s complaint that the usage of too many generic terms, including wetland, overflowed lands, swampland, and muck, was hindering scientific studies of peat (Dachnowski, 1920).

Wetland does not imply that the land has to be permanently flooded. If this was the case, such lands would simply be called “submerged lands” or “flooded lands” rather than wetland. Instead, wetland suggests that land that is noticeably wet for various periods—land that is periodically wet and, when not, may be dry or at least exposed to air for some time. Wetlands include both periodically and permanently flooded lands (see Chapter 2), yet the latter are typically restricted to shallow water areas that often support either free-standing plants like reeds, shrubs, or trees or rooted floating-leaved aquatic plants like water lilies, unless wave energy and other factors prevent their colonization.

When considering periodically wetlands, the frequency and duration of flooding and/or soil saturation (near the surface) need to be taken into account. After all, it is the recurring prolonged wetness that exerts significant stress on vegetation to exclude most plants from growing in wetlands. The fundamental questions for defining wetlands, therefore, include the following: (1) How long and at what frequency must an area be wet? (2) Must wetness occur during the growing season or is nongrowing season wetness also important to consider? (3) Should wetness occur to the ground surface, or if not, what soil depth is critical? These questions should be kept in mind when reviewing existing wetland definitions. The answers to these questions are vital to developing criteria and a set of reliable indicators (e.g., plant, animals, and soils) to validate the occurrence of wetland.

Numerous wetland definitions have been developed for various purposes. The earliest wetland definitions were created for scientific studies or management purposes, with the more widely used ones created to serve as the foundation for wetland mapping projects. Since the 1960s, other definitions have been formulated to establish limits on what “wet” lands should be regulated through various wetland laws and government wetland regulations and policies.

SHALER’S WETLAND DEFINITION (1890)

One of the earliest reports on U.S. wetlands was Nathaniel Shaler’s General Account of the Freshwater Morasses of the United States published in 1890. This U.S. Geological Survey report focused on inundated lands and included what is perhaps the nation’s first national wetland classification system (see Chapter 8). In preparing a table with the estimated acreage of inundated lands east of the Rockies, Shaler included the following definition of “swamp”:

all areas … in which the natural declivity is insufficient, when the forest cover is removed, to reduce the soil to the measure of dryness necessary for agriculture. Wherever any form of engineering is necessary to secure this desiccation, the area is classified as swamp.

In calculating the total wetland acreage, he also included “areas of alluvial lands subject to inundations in the tillage season to such an extent that agriculture is unprofitable until the land is drained or diked.” Consequently, Shaler’s concept of wetland (swamp) is quite broad and includes consideration of the effect of soil wetness on land use, namely, farming.

SCIENTIFIC WETLAND DEFINITIONS

Depending on the field of study, wetland definitions may focus on particular attributes as noted by Lefor and Kennard (1977) in their review of inland wetland definitions. A hydrologist’s definition of wetlands would focus on the fluctuations in the water table and on the frequency and duration of flooding. A soil scientist’s definition might center on the presence of certain soils, mainly poorly drained and very poorly drained soils, plus soils that are frequently inundated for long or very long periods of time that affect crop production (e.g., soils that are too wet to grow corn and other crops without artificial drainage). A botanist’s definition would emphasize the occurrence of certain plant species and certain plant communities and the wetness conditions promoting their colonization. A fish and wildlife biologist’s definition might stress the characteristics associated with fish spawning and nursery grounds and with wetland-dependent wildlife like waterfowl, shorebirds, wading birds, beaver, muskrat, frogs, salamanders, turtles, and alligators. A civil engineer’s definition of wetland would likely highlight the wetness conditions in the soils that affect the ability of the substrate to support construction of roads, bridges, buildings, and similar structures. Thus, a plethora of wetland definitions could be developed based on different areas of expertise or interest.

Current wetland definitions are largely biologically based, since professionals in wildlife biology and botany were among the first to recognize the values that wetlands contribute to society in their natural, unaltered state. Since vegetation patterns are readily observed in most cases, wetland definitions tend to emphasize certain plant communities associated with waterbodies or waterlogged soils. Such communities provide vital habitats for fish spawning and nurseries and support unique forms of wildlife and plant species, and depending on their landscape position and wetness properties, they provide other valued functions such as flood storage, nutrient recycling, water quality renovation, and shoreline stabilization (e.g., Tiner, 2013; Mitsch and Gosselink, 2015).

The most widely used of the scientific definitions in the United States were developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which has a long history of interest in wetland conservation given their significance as critical habitats for many of the nation’s fish and wildlife species. In order to provide more effective management of these habitats, the FWS has been monitoring the status of wetlands in the country since the 1950s. Two wetland definitions were developed to aid in performing inventories of U.S. wetlands. More recently, another scientific wetland definition was formulated by the National Research Council’s (NRC) Committee on Characterization of Wetlands as the reference for conducting a review of the federal government’s wetland delineation practices. Canada and other countries have developed wetland definitions for their own inventories. These definitions are briefly discussed later.

EVOLUTION OF THE U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE WETLAND DEFINITION

During the 1950s and 1960s, the FWS initiated a nationwide inventory of wetlands important to waterfowl and follow-up surveys of key areas (e.g., coastal wetlands). In conducting these inventories, the FWS used the Martin et al. (1953) wetland classification system based on the following definition:

Wetlands are “lowlands covered with shallow and sometimes temporary or intermittent waters. They are referred to by such names as marshes, swamps, bogs, wet meadows, potholes, sloughs, and river-overflow lands. Shallow lakes and ponds, usually with emergent vegetation as a conspicuous feature, are included in the definition, but the permanent waters of streams, reservoirs, and deep lakes are not included. Neither are water areas that are so temporary as to have little or no effect on the development of moist-soil vegetation. Usually these temporary areas are of no appreciable value to the species of wildlife considered in this report.”

Shaw and Fredine (1956)

While the focus on habitat for certai...