![]()

1

Irma Stern in a Global Context

Expressionist Influences

Throughout Irma Stern’s life, Africa and Europe intersected in ways that profoundly shaped her career. One of the most important intersections occurred during Stern’s stay in Germany from 1910 to 1920. This ten-year period coincided with the height of Germany’s colonial activities, the emergence of expressionism, the onset of the First World War, and Germany’s economic and political collapse at the beginning of the Weimar years. Having arrived in Germany as a teenager and left as a young adult, Stern treated her time in Berlin as her opportunity to explore her own artistic identity. With guidance from expressionist artists such as Max Pechstein, Stern used the Berlin milieu—a society fascinated by conversations about difference—to understand how racial difference contributed to new perspectives on both formal and thematic approaches to art. Being in Germany during this pivotal historical moment allowed her work to be noticed by critics and thinkers from Europe and North America, including African American philosopher Alain Locke. This early transatlantic artistic engagement with expressionism established Stern’s global perspective as an artist and encouraged a genuine curiosity for other cultures that fueled her desire to record her travels on canvas.

Expressionist Beginnings: Artists Exploring Questions about the State

As there is no single definition of the term, scholars agree more broadly that expressionism constituted a break with Western artistic conventions of naturalism and an embrace of the “universal, metaphysical, and transnational power of the new art forms.”1 For young artists seeking opportunities to channel their energies into a more critical assessment of their rapidly changing society, expressionism freed them from state-sanctioned academic principles and guided them toward a more vibrant sense of individual engagement with the world.2 Many expressionist artists used their work to respond to the ways in which Germany was transforming itself and developing its national ethos. Since France was still considered the center of European art world in the early twentieth century, German artists viewed expressionism as one way to articulate new questions and artistic issues in a more culturally specific way. Scholar Carol Washton Long writes that compared with other artistic movements in Europe at the time, “Expressionism was more involved with the relationships between art and society, art and politics, and art and popular culture. Because of this engagement, artists and critics dealt with a wider range of questions about the artists’ interactions with the state.”3

The Eternal Child and the Context of the First World War

Stern’s study in Germany coincided with the emergence of expressionism, giving her the opportunity to interact with artists who were critically engaging with politics in their work. Through her relationship with German artists such as Max Pechstein and her immersion in the German cultural environment that nurtured its beginnings, expressionism made the most significant and long-lasting impact on Stern’s artistic career by influencing her stylistic approach and her understanding of the relationship between an artist and society.

Stern’s global mindset was further developed by the onset of the First World War, the political event that would reshape world order. Although no fighting occurred on German soil, the First World War’s devastation created an international political and social vacuum that left an impression on Stern and an entire generation of artists who struggled to describe their frustrations in visual terms. Artists responded to the conflict in different ways. Many artists supported the war, but few were prepared for the violence that resulted from trench warfare and new weaponry, such as chemical weapons and machine guns.4 Franz Marc, for example, volunteered as a soldier and died in battle in France. Käthe Kollwitz lost her son in Flanders and used much of her work afterward to address themes related to war and suffering.

Stern bore witness to the social and political upheaval around her, noting the war’s effect on Germans’ daily lives. At Christmastime in 1914, she wrote in her diary in somewhat hyperbolic terms,

And Christmas trees are fragrant in the streets. The rushing, warm blood is steaming—I see wasted lives, thousands, millions of men. And are we to wait here and celebrate Christmas, this feast of peace, while everything is running with blood, among all those staring dead eyes? Every festive light reminds one of the broken hearts of women, of bitter, innumerable tears shed by children, of disappointed hopes, of all this horror, of the war. And is this how we are to celebrate Christmas?5

Stern spent time with German soldiers who were recuperating from war injuries, painting with them and entertaining them. Her interactions with people, especially youth, raised her awareness of the war’s impact on German society. In 1916, while still a student at the Weimar Academy, Stern painted her own response to the war in an oil painting she called Das Ewige Kind (The Eternal Child), which marked a turning point in her understanding the relationship between art and society (Figure 1.1).6 After seeing a gaunt young girl on a tram, Stern decided to paint her.

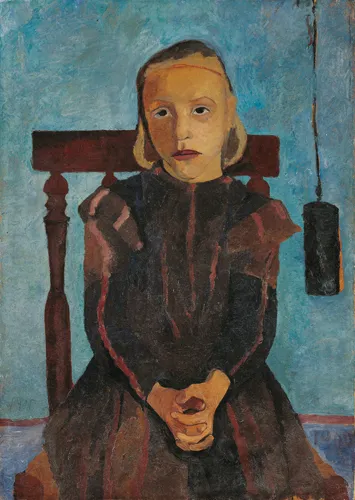

Figure 1.1 Irma Stern (1894–1966), The Eternal Child (1916). Oil on board. © 2020 Irma Stern / DALRO, Johannesburg / VA GA at ARS, NY. Courtesy of Rupert Family Foundation, Rupert Museum, Stellenbosch, South Africa. (See Plate 3.)

The Eternal Child depicts a young German girl sitting on a high-backed wooden chair, holding a bouquet of flowers. Her wide-set, dark-brown eyes and long nose dominate her face. The child has a slightly disheveled look; the part between her shoulder-length braids is crooked, and the red and blue bow on her dress is askew. Her lips are pursed in a position that forms a slight frown, just enough to indicate that she is uncomfortable. Her dress, a patchy, red frock, has a white lace collar and frayed sleeves. The beige background gives no indication of location or time of day, bringing more focus to the child’s grim expression.

The Eternal Child conveys Stern’s desire to understand German youths’ plight. German men were particularly vulnerable since they were sent to fight on the front lines, yet they had no political voice. As an upper-middle class family visiting from South Africa, the Sterns remained insulated from many of the hardships faced by lower-class Germans who were forced to participate in combat. But, they were not isolated from the tens of thousands of grief-stricken families mourning lost children. Throughout the country, the war’s violence had permanently altered citizens’ views on their role in German society, particularly for young people. Observing severely wounded veterans and starving children heightened her political awareness and made her more attuned to social issues in general. Years later, she reflected on her decision to paint the child, stating, “I shuddered and awoke to my own generation.”7

Stern’s The Eternal Child was her first serious painting that demonstrated artistic vision and social consciousness, fitting within the tradition of women artists such as Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn-Becker.8 In fact, The Eternal Child bears similarities to Modersohn-Becker’s 1900 oil painting, Girl with a Pendulum (Figure 1.2).9 Both paintings focus on young girls sitting awkwardly on a chair. Painted sixteen years apart, the two paintings each capture a malaise that goes beyond the typical childhood worries and seems to evoke deeper concerns. For both works, the child’s sullen facial expression and few details in the background focus the viewer’s attention on the child’s discomfort. Having shared instructor Fritz Mackensen with Modersohn-Becker and read her diaries, Stern began to understand how to shape her female subjects from a woman artist’s perspective.10

Figure 1.2 Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl with a Pendulum. Oil tempera on cardboard, 1900. © Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Photo © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

“You Are Equipped with Your Own Language”: Irma Stern and Max Pechstein

The Eternal Child revealed Stern’s ability to interpret contemporary society through the medium of painting, a practice that she would continue throughout her career. The work attracted the attention of expressionist artist and political activist Max Pechstein, who would become Stern’s primary expressionist mentor in Germany.11 Pechstein was one of the most prolific expressionist artists, working across media in drawings, lithography, painting, and woodcuts, in addition to his political work creating posters for socialist causes.12

Over several decades, Stern and Pechstein developed a deep bond characterized not only by an interest in painting but also by a shared curiosity about non-Western cultures. Stern brought her So uth African childhood experiences to the relationship, whereas Pechstein had recently returned from living in Palau, the German colony in the South Pacific. In their letters and through the stylistic similarities in their work, it is evident that Stern and Pechstein were bound by a mutual desire to be innovative as artists while illustrating an understanding of the world outside of Europe.

By her own account, Stern met Pechstein in 1916 or 1917, after she painted The Eternal Child, through her mother’s friend.13 She described her initial encounter with Pechstein as follows:

I showed Mr. Pechstein some of my drawings and paintings to hear his opinion. To my great joy, he liked them all. . . . The next day, he visited my studio. He spent the entire afternoon looking at my work, and when he left, it was as if we had known each other for years, such good friends we had become.14

Pechstei...