eBook - ePub

Tudor Houses Explained

Britain's Living History

Trevor Yorke

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 64 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Tudor Houses Explained

Britain's Living History

Trevor Yorke

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The Tudor period was dominated by King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I. The houses still standing from that time are typified by black and white timber framed buildings and rambling rows of quaint cottages around a village green. This book explains the rich range of domestic houses built during the era. There are five separate sections, which deal with social change; structure and materials; styles and dating details; interiors; and gardens and landscapes. There is also a quick reference guide to identify the use of Tudor styles in more recent times. This is an invaluable, well illustrated guide for anyone interested in the history of Britain's domestic architecture.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Tudor Houses Explained è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Tudor Houses Explained di Trevor Yorke in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Architecture e History of Architecture. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

ArchitectureCategoria

History of ArchitectureCHAPTER 1

Tudor Housing

TOWN AND VILLAGE

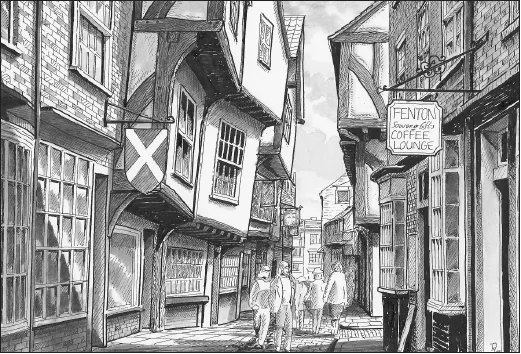

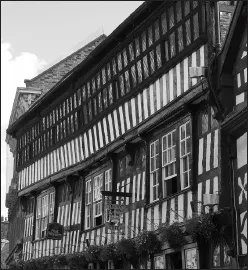

FIG 1.1: THE SHAMBLES, YORK: This offers a rare impression of how many Tudor towns would have appeared, with narrow streets and overhanging buildings jostling for space. The Shambles contains houses from the 15th century onwards, with their lower storey used as shops – in this case they were originally butchers.

Rarely has there been a time like the 16th century when one family so dominated events, their struggles to establish a dynasty changing the course of British history. Henry Tudor, his son and grandchildren took their largely faithful population on an economic and religious roller-coaster ride, destroying medieval establishments and customs but laying the seeds for the modern state. Power began to shift from the local gentry to a rapidly expanding court and its ministers, and they expressed their control in lavish and extravagant houses. Marriage guidance counsellors were also kept busy!

When the first Tudor king, Henry VII (1485–1509) took the throne after defeating Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485 he used marriage rather than war to secure his family’s hold on power and heal over wounds, a policy that helped leave a significant surplus in the treasury on his death. Unfortunately his son, the over indulgent Henry VIII (1509–1547), managed to spend it all despite sizeable windfalls from the sale of property after he had dissolved the monasteries in the late 1530s. His children, the Protestant Edward VI (1547–53) and Catholic Mary I (1553–1558), fought over the direction of Henry’s other legacy, the Church of England, before Elizabeth I (1558–1603) sought compromise to bring a tense peace to sectarian frictions. Aided by accomplished ministers, the economy recovered and the country basked in unprecedented national self-confidence, a glorious period that overshadowed her rather sour later years.

FIG 1.2: HAMPTON COURT, SURREY: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was Henry VIII’s ambitious Chancellor and Archbishop of York although it took him 15 years before he actually visited his minster! He had spent much of his efforts building himself a palace more glorious than any house of the monarch, probably a mistake as his failure to secure a divorce for the king brought him down and this vast brick palace fell into Crown hands. It is notable as one of the first buildings to express elements of the Renaissance before the separation from the Catholic Church left us isolated from the main flow of European architectural fashions.

SOCIETY

Population and class

The Tudor period witnessed a reverse in the long period of population decline. Ever since it reached a peak in around 1300, poor harvests and then the Black Death had devastated all levels of society so that when Henry VII took the throne there were fewer than three million people in the country. The number grew progressively through the 16th century to around four million by 1600. At the top were the nobility, a relatively small group of powerful families, and below them an expanding class of gentlemen, including rich merchants, courtiers and men of law. Next down the ladder were the yeoman farmers, who were sometimes as rich as those above them but more interested in acquiring land than expressing their fortune in heraldic display.

Below these were the vast majority of the population, a complicated and regionalised range of people from tenant farmers down to landless labourers. More than half of these lived on or below the subsistence level, only able to supply themselves with sufficient food, clothing and shelter to survive. The situation for the poor worsened through much of the 16th century as wages could not keep up with inflation, enclosures in some parts of the country deprived them of land, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries took away a vital source of charity. Poverty grew and vagrancy was a constant source of problems for polite society, especially in London.

One of the after effects of the Black Death was the breakdown of the rigid feudal system, with landowners finding it difficult to keep labourers tied to one location when there were too few people to do the work. Although this situation varied from area to area it gave some lower down the social ladder the opportunity to escape poverty and acquire land. By the 16th century there were families whose growing wealth enabled their sons to gain an education and, as a result, a position at court or in law, and the classification of ‘gentry’.

Wealth and trade

The majority of the population were involved in agriculture and although many lost out in villages where there was a restructuring of the land, the larger, more securely tenanted farmer could prosper, especially as food prices increased steadily through the century. Many of these changes came about due to the high price of wool, which more than tripled in price by mid century, and landowners converted arable areas to pasture, which required less labour, only for some to convert it back later when the price fell!

FIG 1.3: NEWSTEAD ABBEY, NOTTINGHAMSHIRE: The break with Rome initiated by Henry VIII’s demand for a divorce from his first wife gave the Crown the opportunity to dissolve the monasteries and acquire their land and wealth. The religious houses were in part initiators of their own downfall as many orders had abused their position in the public’s eyes and Henry exploited their unpopularity. He first had the smaller establishments closed in 1535–6 and then the larger abbeys in 1538–40. The priory in this picture had the cloisters converted into a country house, while the church was stripped of its assets and just the shell remains today.

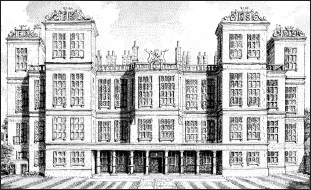

FIG 1.4: HARDWICK HALL, DERBYSHIRE: There was now greater fluidity in society than there had been in the medieval period, though for women riches could only be gained through marriage. One of the most notorious 16th-century ladies was Elizabeth of Shrewsbury, whose family were bankrupt squires two generations before; through calculated marriages she amassed a fortune and became the richest woman in England after the queen. Her final glory was Hardwick Hall, designed by Robert Smythson, the leading mason of the time, and built overlooking her earlier project, the Old Hall, which was barely finished before she started this one! Its mass of glass was characteristic of the spectacular country houses built in the last decades of the 16th century, the towers at each corner acting partly as buttresses to support the walls weakened by all the windows.

Industry began to prosper under the Tudors. Textiles were the most profitable but mining, quarrying, smelting iron and shipbuilding became important in certain areas, increasing the consumption of wood and charcoal, which began to deprive the house builder of the best timber and the householder of fuel for fires. In response coal, which had been limited to areas where it was freely available, was in growing demand in the major towns and cities that could be reached by coastal vessels, principally coming from the Newcastle area (this was known as sea coal).

Town and country

Most people lived in villages and hamlets. These were not the neat and trim chocolate box image that we might imagine today but a working community with poor roads and a scattered appearance, albeit surrounded by well managed fields and woodland. The more established farmers had enough land to provide much of what they needed; however, those with small plots or no land were vulnerable when times were hard. No one was completely self sufficient, all relying to some degree on the markets, fairs and local towns where they could buy goods.

With the exception of London, which had a population of around a quarter of a million by 1600, most urban areas were small by today’s standards. Bristol, Norwich and York had between 10,000 and 20,000 residents but all the other towns had less – some were barely more than a large village. While many grew relatively rapidly in this period, especially ports and centres connected with successful trades like wool, a few fared less well with business lost after the end of pilgrimages, the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the silting up of rivers. Where there was expansion, little of it was planned; roads were usually unpaved, drains rare and running water available to only an exceptional few. As a result, outbreaks of disease and fire were severe, both spreading rapidly through the congested timber framed communities.

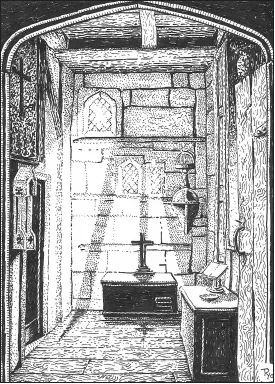

FIG 1.5: The Reformation of the 1530s and the more intense actions taken in Edward’s reign resulted in the removal of images and ended pilgrimages to holy sites, depriving a number of towns and cities of the trade which they had formerly relied upon from pilgrims. It also made those who wished to hear Catholic mass from then on worship in secret and hide their allegiance through ingenious plans of houses and decorative symbols. Travelling priests had to be hidden out of view of the authorities when they came knocking, so priest holes in which they could hide were built by Catholic families. In this example, it was under the altar in the middle of the picture. The priests may have been less appreciative though if they had known it used to be a garderobe (toilet)!

HOUSING

The general improvement in the standard of living and increased wealth of those in a fortunate position was reflected by a rise in the number of houses erected in the Tudor period. This was especially notable in the second half of the century, with the stability of the Elizabethan Age encouraging many to spend their income on the latest timber framed, stone or brick structure, displaying their success and ambitions in its decoration. This Great Rebuilding (a term coined by the 20th century historian W.G. Hoskins) affected areas at different times. It was already underway in counties like Sussex and Kent when Henry VII took the throne; in the south, east and the Midlands it peaked in the late 16th and early 17th century, while highland areas to the north and west were in some cases as late as the 18th and 19th centuries.

FIG 1.6: NANTWICH, CHESHIRE: Most towns suffered some degree of devastation from fire during this period, a problem intensified by the lack of planning and tightly packed timber framed houses. Nantwich had such a fate in 1583 and many of its timber framed buildings in the town centre date from the rebuilding afterwards, including the impressive Crown Hotel built in 1585 with a fashionable mass of windows.

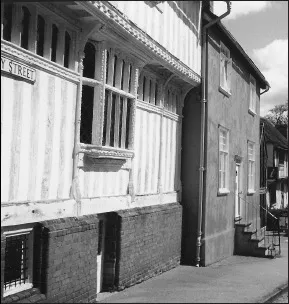

FIG 1.7: LAVENHAM, SUFFOLK: Although a village in size today, this was an important town in the 15th and 16th centuries and is still blessed with timber framed houses built with wealth from the wool trade.

Most new houses were built on the site of older ones, and sometimes even included parts of its former structure. They were generally individual properties built for or by the householder for their own use; there was little speculative building and planned developments or rows of cottages were rare. In some towns regulations put a thin stone wall between properties to reduce the risk of fire spreading, while others preferred a gap between properties to avoid boundary disputes. Architects were unknown in this period, instead local masons and carpenters of varying skill would often plan and build houses, with the builder (landowner) having the responsibility for supplying materials and sometimes labour.

Large houses

The grand houses of the nobility and gentry were still designed with defence in mind in the early Tudor period, even if this was rather more for display than actual conflict. A common arrangement was to have a battlemented wall surro...