![]()

SECTION I

The Events of May 1–4, 1970

An Overview

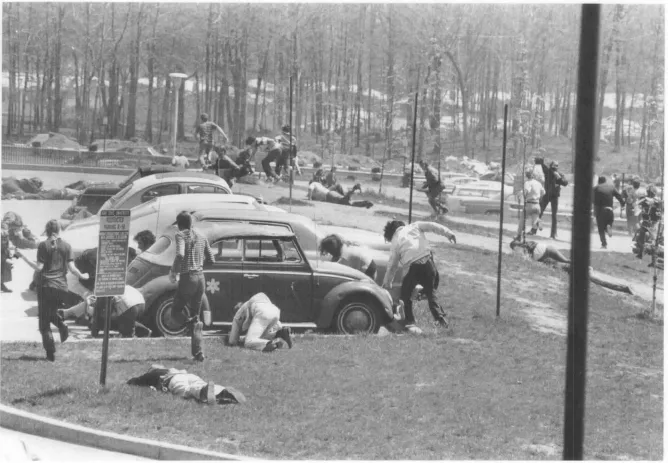

Students taking cover as the Ohio National Guard fires into the Prentice Hall parking lot on May 4, 1970. Photo by Doug Moore.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The five essays in this section provide an overview of the events associated with May 4, 1970, when four students—Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer, and William Schroeder—were killed and nine others—Alan Canfora, John Cleary, Thomas Grace, Dean Kahler, Joseph Lewis, Donald MacKenzie, James Russell, Robert Stamps, and Douglas Wrentmore—were wounded by the Ohio National Guard.

James Best, an emeritus member of Kent State University’s political science department, describes the events through a secondary analysis of a large number of resources. Written in late 2008, his essay provides the reader with a factual background for looking at the events on the days prior to the shootings, as well as the events of May 4.

Jerry M. Lewis, an emeritus member of Kent State’s sociology department, reviews, in two essays, books that have been published about May 4, including legal controversies, memorials, children’s books, and novels. This is followed by an essay on television documentaries that focused on May 4.

Lewis and Thomas R. Hensley, a member of Kent State’s political science department, conclude this section with an essay using many of the sources discussed in the Best and Lewis essays to attempt to identify the historical inaccuracies associated with May 4. Their approach is to raise and provide answers to twelve of the most frequently asked questions about May 4.

![]()

The Tragic Weekend of May 1–4, 1970

James J. Best Kent State University

In this chapter we present a historical narrative of the events of May 1–4, 1970, and an analysis of the context in which those events took place, a narrative that serves a number of purposes. For those unfamiliar with what happened in Kent, Ohio, during the period of May 1–4, the narrative provides a time-ordered description of the major actors and activities, making use of all the major published as well as many unpublished descriptions and analyses of the events, as well as testimony given by the participants during the 1975 civil suit trial. From these sources we reconstruct in sufficient detail the fateful events of those four days.

Because no action occurs in a vacuum, it is important for us to present and analyze the social, historical, and political context in which the shootings took place. We concentrate our efforts on several factors that we consider important: the social context provided by the city of Kent, the historical context of demonstrations on the campus of Kent State University, and the political context provided by the statements and actions of President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew, as well as the Republican primary campaign of Governor James Rhodes.

The Kent State Incident

We have asked a number of questions during this narrative: What factors led to the fatal confrontation between National Guardsmen and demonstrators on Monday, May 4? Why did Kent Mayor Leroy Satrom call for the Ohio National Guard after only one night’s disturbances? Why did city and university officials think that the National Guard had complete control of the campus on May 4? Why did Governor James Rhodes make a speech on Sunday morning, May 3, which served to inflame the emotions of many who heard or read about it? Were radicals involved in the events of May 1–4? How did townspeople and students react to the shootings? What impact did the shootings have on the larger society in which they occurred?

In reconstructing these events we have had to choose which sources to use and, when sources conflicted, which sources to believe. Extensive use has been made of two major works—James Michener’s Kent State: What Happened and Why1 and The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest2 (the Scranton Commission Report)—although each work has its defects. Michener’s book suffers from his research methods and his political and educational biases; he selectively interviewed participants in the weekend’s events and uncritically accepted what he was told. Politically, Michener believes in the democratic process and, while he understood the frustrations students felt when they learned of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, he could not condone the damage to downtown businesses on May 1 or the burning of the ROTC building on May 2. After researching his book, Michener developed a great affection for Kent State University and its administration, particularly President Robert White, which colored his evaluation of White’s role in the weekend’s events. These criticisms notwithstanding, Michener has the uncanny ability to recreate the ambience of a situation, particularly Blanket Hill on the morning of May 4: you can almost smell the tear gas and see the masked Guardsmen striding up the hill.

The Scranton Commission Report is concerned with establishing for the public record what “really” happened. The quest to describe what happened is both the strength and weakness of this book; it stands as the most authoritative statement of what happened, but it rarely explores inconsistencies between various participants’ testimony, leaves unanswered a number of questions regarding the motivation of many participants, and is relatively unconcerned with the impact of the shootings on subsequent events.

A number of other reports were useful as well. The Knight newspaper report, published less than three weeks after the shootings, is important because the reporters interviewed many of the participants, particularly Guardsmen, shortly after the shootings. The decision to focus on the events of May 4, however, leaves unanswered a number of questions regarding events earlier in the weekend. Nonetheless, “The fact that the Journal got this report out so rapidly and with relatively few serious errors set the tone for facts that govern the remainder of the studies.”4 The report subsequently won a Pulitzer Prize.

The Joe Eszterhas and Michael Roberts’ book on Kent State, a journalistic quickie, was published after the Knight newspaper report but before the Scranton Commission Report and the Michener book. It is replete with inaccuracies, and the authors rarely cite the sources of their information.5

Peter Davies’s The Truth About Kent State argues, primarily through an analysis of photographs of the shootings and testimony before the Scranton Commission, that the shootings were the result of a conspiracy on the part of certain Guardsmen.6 Readers of this work should remember that it was written in an attempt to convince the Justice Department to convene a federal grand jury to investigate the shootings.

Another conspiracy theory is advanced by Charles Thomas in “The Kent State Massacre: Blood on Whose Hands?”7 For Thomas, the Guardsmen and students were merely pawns in a larger game being played by the Nixon administration; Kent State was a demonstration of President Nixon’s get-tough policy toward student dissent, and after the shootings President Nixon and Attorney General John Mitchell consciously attempted to cover up the administration’s role in the fateful events. Thomas’s allegations are at variance with other research on the subject, and many are unsubstantiated: he reconstructs conspiratorial conversations by Guardsmen on May 4, conversations that have never been verified by anyone else. His research is based, however, on materials to which he had access as an archivist working in the National Archives, material generally not available to other researchers. As a result his analysis and conclusions may be correct but are impossible to corroborate independently.

The Phillip Tompkins and Elaine Anderson8 and Stuart Taylor et al.9 books are based on research conducted by Kent State faculty and students shortly after the shootings. The former focuses on communication failures within the administration and between administrators and students as they contributed to the events of May 1 to 4. Taylor and his colleagues focus on KSU student perceptions of the events, and their survey research data represent our best knowledge of the phenomenon.

Only two written works present the perspective of the Guardsmen. Ed Grant and Mike Hill’s book, although factually incorrect on occasion and leaving time gaps, does provide some insight about what Guardsmen were thinking on Saturday and Sunday night.10 William Furlong’s piece in the New York Times Magazine also provides some insight as to why Guardsmen turned and fired on the demonstrators.11

Three unpublished sources have been useful as well. The Justice Department Summary of the FBI Report was entered by Congressman John Seiberling in the Congressional Record.12 Volume IV of the Report of the Commission on KSU Violence (the Minority Report) represents an attempt by a group of KSU faculty and students to write a history of the events; division within the committee is reflected in the fact that the volume is called the Minority Report, although a “majority” report has never been published.13 The Minority Report’s principal weakness stems from its attempt to prove that radicals and outside agitators were responsible for the shootings. The report is valuable because it includes a great deal of information from people who did not testify before the Scranton Commission or talk to Michener and his researchers. The third source has been the transcript of the 1975 civil suit trial, in which the major participants testified.14 Unfortunately, the plaintiffs’ case was poorly handled, and potentially illuminating questions were rarely asked.

These materials constitute the primary data sources for our description of the events of the period. They have been supplemented by a body of research by social scientists at Kent State who have focused on one or more aspects of the events; their research is included in this book.

Our primary job in this chapter is to compare and contrast these sources so that we might construct as accurately as possible a historical narrative of events. From this narrative we have sought answers to a number of important questions. We have not asked all the questions possible; nor have we answered all the questions we have asked. But we have taken great pains to address issues that we deem most important.

The Social, Political, and Historical Context

Kent, Ohio, is a small city located approximately thirty miles south of Cleveland and ten miles east of Akron, an intrinsic part of the industrial heartland of northeastern Ohio, which has been heavily dependent on the steel of Youngstown, the rubber of Akron, and the manufacturing and commerce of Cleveland. Kent was first settled in 1805, and the waterpower of the Cuyahoga River made industrial development attractive and inevitable. Later, the construction of the railroad through Kent insured that local manufacturers would have access to markets and that freight trains would daily tie up traffic in the center of the town. In 1910, after substantial lobbying, the state legislature agreed to create a state normal school in Kent on fifty-four acres of land donated by William S. Kent, a local businessman; the purpose of the school was to train elementary school teachers, but its early leaders had greater ambitions. The first students were admitted in 1913, and the school achieved the status of a four-year college in 1929 and university status in 1938.15

As the university grew, so did the town. In 1913 the normal school enrolled forty-seven students, while the town had a population of approximately 5,000; by 1970 the university had grown in enrollment to over 21,000 while the town (now a city) had a population of 28,000. Much of the growth for both the city and university had occurred in the twenty-five years between the end of World War II and 1970. By 1970 the city had developed into the largest population center in Portage County, and the university had become the second largest in the state and one of the twenty-five largest in the United States. The size of the university insured that it would be the dominant industry in the city as well as the county. In the early 1970s KSU employed over 2,500 people and had an annual payroll in excess of $20 million and a budget of over $50 million.

There were three Kents—the downtown areas, the residential areas, and the university. Downtown Kent, centered around the intersection of state routes 43 and 59, is unlike the center of most college towns. Aside from the two banks, two drugstores, two movie theaters, the post office, and a grocery store that you expect in a college town in 1970, there were no art galleries, boutiques, men’s specialty shops, or good restaurants. Michener describes downtown Kent in these terms: “Route 59, which runs east and west, is a tacky...