![]()

Chapter 1

The USSR, World Revolution and the British Communist Party, 1917 – 1941

Our task is to generalize the revolutionary experience of the working class, to purge the movement of the corroding admixture of opportunism and social-patriotism, to unify the efforts of all genuinely revolutionary parties of the world proletariat and thereby facilitate and hasten the victory of the Communist revolution throughout the world.

Founding manifesto of the Communist International,

Moscow, March 1919

The 1917 Revolution

Few outside the closed circles of European monarchy mourned the toppling of the Tsar of Russia in February 1917. His unsophisticated absolutism had brutally oppressed his own people and resulted in disastrous military loss, even by the standards of those engaged in the seemingly endless carnage of the Great War that had begun three years earlier. The instability that followed was finally laid to rest when the Bolsheviks seized power in October of the same year on a programme of land, bread and peace that won the support of the masses. Their revolution only found favour abroad with socialists who shared the communist vision of a world freed from the destructive competition that had condemned millions to poverty, exploitation and war. The Bolshevik programme threatened the great powers, not just because of its immediate impact on the war, but through its message to ordinary people that another world was possible if they could wrest power from their rulers. Bolshevik leaders like Lenin and Trotsky made no secret of their belief that the success of their own revolution rested on similar developments in other countries, particularly the advanced nations of Western Europe and North America. Without such developments their revolution would be strangled. The actual reaction of their counterparts in Great Britain will be discussed in Chapter 2.

Prior to 1914 socialist parties had met across the globe as the Second International – an organization that included huge parties like the German Social Democrats. The Second International effectively collapsed as most of its members, including the Labour Party in the UK, fell prey to national chauvinism, supporting their respective sides as war broke out in 1914. A conference to bring together those who had stood out against militarism was held in Zimmerwald in Switzerland in 1915: thirty-eight delegates attended including Bolsheviks and members of other organizations from Russia. The three British delegates from the British Socialist Party (BSP) and Independent Labour Party (ILP) were refused passports and so could not attend. Despite disagreements reflecting different political positions, there was unity around a strident anti-war ‘Zimmerwald Manifesto’, although its impact at the time was minimal.

The supporters of the Bolsheviks internationally were those socialists who had opposed the war from its beginning in 1914. They were a minority – most of those who had previously described themselves as socialists, like those in the British Labour Party, dropped their internationalism overnight to support their governments and rulers as the battle lines were drawn up. In the United Kingdom, socialist opponents of the war were organized in small organizations like the BSP, ILP and Socialist Labour Party (SLP). Their numbers included the former suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. Anti-war agitation was a risky business and many political and shop floor trade union revolutionaries found themselves imprisoned when their activities were considered to have fomented unrest amongst workers and troops. Amongst these were the Glasgow school teacher and Scottish republican socialist John Maclean whose speech from the dock prior to his five-year prison sentence for sedition in May 1918, exhorted workers to tear down the capitalist system: ‘I am not here as the accused, I am here as the accuser of capitalism, dripping with blood from head to foot.’ By this time Maclean had been appointed Bolshevik consul in Glasgow (a position never recognized by the UK government).

British Bolsheviks

Socialists in Britain (most of whom would join the Communist Party) were quick to advocate support for the Bolsheviks after the 1917 October Revolution. Their influence was a factor in the opposition to government attempts to undermine the revolution that will be discussed in Chapter 2. At the war’s end Europe was in ferment as old empires crumbled – revolutionary change, fomented by adherents of the Communist International, was in the air. In the wake of the carnage of the Great War the Labour Party opposed, although not actively, interventions against the new Soviet state. In January 1919, 500 delegates from 350 organizations formed the Hands Off Russia campaign which determined action to force withdrawal of British forces from Russia. In May 1919 British left-wing socialists argued for support for a European-wide general strike against anti-Bolshevik interventions. This was watered down by Labour leaders, who opposed Bolshevism but supported the right of the Russian people to determine their own future. The climate for change was reaching a crescendo. That summer, strikes in Glasgow and Liverpool were met with military force due to their insurrectionary character.

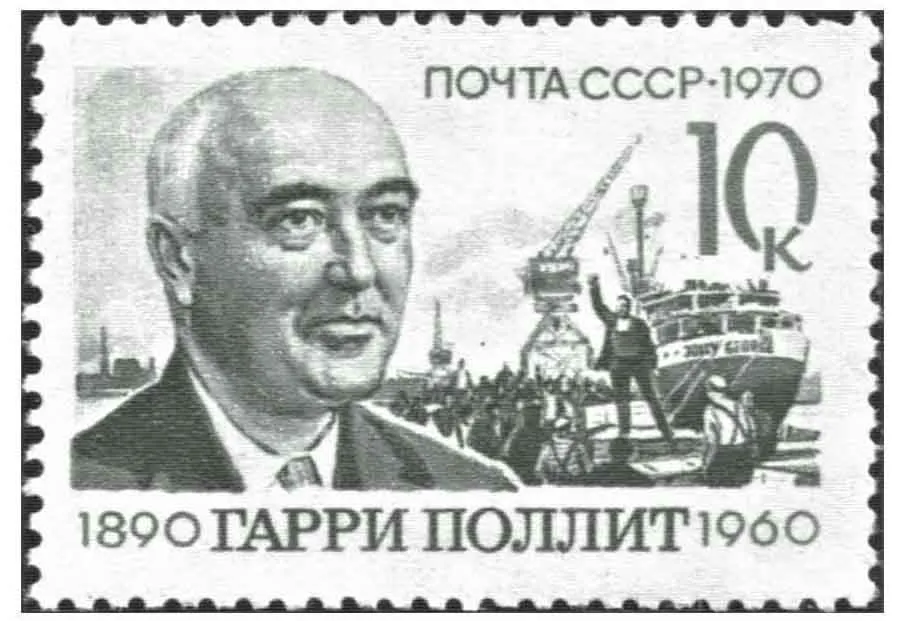

In May 1920, militants amongst the London dockers – notably Harry Pollitt who was to become a leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) – discovered that a cargo ship, the Jolly George, was being loaded with a consignment of weapons for the Polish Army who were at that time involved in an aggressive war against the young Soviet state. They successfully sought official support for this boycott and the Jolly George eventually sailed for Danzig without the offending arms. A National Council of Action was formed by the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to counter the threat of further military intervention against Russia. Over 300 local councils were created but these were far from pro-Bolshevik – some refused Communist Party affiliation after the formation of the Party in July (see below). Others were more left wing – sixty-six added the call for British military withdrawal from Ireland to their demand concerning Russia, but the call for a general strike was reduced by the national leadership to one of demonstrations on 22 August. By October 1920, the councils had all but disappeared as the threat of military action by the UK government receded.

Trial in Glasgow of left-wing leaders following the January 1919 strike. Willie Gallacher is second from left. (Wikimedia Commons)

1970 Soviet postage stamp celebrating Harry Pollitt and the Jolly George incident. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Comintern

In March 1919 the new Soviet government in Russia called together delegates from across the world in Moscow to declare a Third International. Although attended by fewer delegates than Zimmerwald, its influence based on the prestige and success of its hosts, was considerably more profound. In order to ensure that it represented truly revolutionary socialist aspirations rather than the reformist ones that dominated its predecessor, the Executive (influenced by Lenin) laid down twenty-one conditions for membership which were formally adopted at the second congress in 1920. The character of these can be judged by the third condition:

In almost every country in Europe and America the class struggle is entering the phase of civil war. Under such conditions the communists can place no trust in bourgeois legality. They have the obligation of setting up a parallel organizational apparatus which, at the decisive moment, can assist the party to do its duty to the revolution. In every country where a state of siege or emergency laws deprive the communists of the opportunity of carrying on all their work legally, it is absolutely necessary to combine legal and illegal activity.*

A number of mass socialist parties in Europe felt able to meet these and affiliate, bringing the organization real strength and purpose. Britain’s left socialists were not among the best-supported exponents of Bolshevik-style revolution: the BSP, SLP and other individuals united to form the Communist Party of Great Britain in July 1920. Membership amounted to only about 3,000 and this reduced in the first few years. The Third International advised the CPGB to seek affiliation to the Labour Party, a mass umbrella organization with growing representation and influence. The aim was to affiliate but remain organizationally independent so that revolutionary socialist principle could be adhered to and argued within the wider labour and trade union movement. Affiliation was rejected (repeatedly and with a hardening of attitude in ensuing years) but would remain an issue for the CPGB with recurring revivals throughout its history, including, particularly, in the closing years of the Second World War. However, at this early stage few doubted the wisdom of such a move and seven candidates were put forward for the 1922 general election, two of whom, Walter Newbold in Motherwell, and Shapurji Saklatvala, in Battersea North, were elected with Labour endorsement (the LP at this time was an umbrella organization rather than a self-contained political party). During their brief spell in parliament (under a Tory government) they worked together to raise issues about unemployment and housing, but only Saklatvala was accepted into the Labour Party parliamentary caucus. Both lost their seats in the general election in 1923 but Saklatvala was re-elected in the 1924 general election (without Labour support) and sat until 1929 as the only Communist MP.

Communist International newssheet, 1919. (Wikimedia Commons)

Lenin and other world Communist movement leaders at the 2nd Comintern Congress, 1920. (красная панорама April 1924/ Wikimedia Commons)

Early CPGB leaflet against intervention in Russia, 1920. (Wikimedia Commons)

Communists in the Period of the General Strike

The period between the two world wars saw capitalism lurch from crisis to crisis and politics polarized as a consequence: fascism emerged in a number of countries, notably Germany and Italy, whilst Soviet Russia remained the only survivor of the socialist revolutions that took place at the close of the Great War. Industrial unrest in the UK formed a good breeding ground for communist ideas and the CPGB grew in influence, if not in size, within working-class areas – particularly those dominated by heavy industry and coal mining where there were strong traditions of trade union militancy. Communist influence in the trade unions was centred on the Minority Movement, an organization formed in 1924 to challenge the right-wing leaderships, and within a year or two it represented almost a million workers. Labour’s rejection of Communist affiliation was based on fear of left-wing takeover, but that did not prevent them from expressing admiration for the achievements of the Bolsheviks in Russia. This caused establishment fears when Labour won a general election for the first time in late 1923. A further general election was required after the collapse of the Labour government in October 1924: a few days before the election the Daily Mail published a letter from the Comintern leader Zinoviev advising the CPGB of the opportunities for sedition that a Labour victory would bring (see Chapter 2). Labour consequently lost the election, the letter itself being eventually revealed as a forgery. However, the lesson was clear: Labour needed to maintain a distance from Communism and its British representatives.

The CPGB’s big chance came with the General Strike of 1926: in support of Britain’s 1.2 million miners who had been locked out by their united employers, the TUC called all workers out on strike in May. The response was massive and the country ground to a halt for nine days. However, fearful of the repercussions of such a challenge to the state, the TUC General Council called off the strike and the miners were left to fight on alone until eventually starved back to work. The CPGB, with only 5,000 or so members, and despite valiant efforts (with other left activists) to fight on to the finish, was simply too small to countermand the capitulation of the movement’s leaders in which it had placed great and misplaced faith. Many CPGB leaders, such as Pollitt, Willie Gallacher from Glasgow, and J.T. Murphy from Sheffield, were already out of circulation having been imprisoned the previous year for seditious libel under the Incitement to Mutiny Act of 1797 (see Chapter 2). The defeat of the General Strike was a major setback for British Communism, and one from which it never entirely recovered due to the deliberate ongoing effort of the mainstream labour movement to keep it on the side-lines.

CPGB banner at a Hyde Park rally during the 1926 General Strike. (Wikimedia Commons)

The USSR After the Death of Lenin

Meanwhile great changes were taking place in Russia. Lenin, whose leadership and tactical skills were quite unrivalled, suffered a massive stroke in 1922 and was largely incapacitated from then until his eventual death in 1924. Leadership, by means of cunning and bureaucratic manoeuvre, was gradually assumed by Joseph Stalin, until his position as Secretary of the Communist Party, with all powers, became quite impregnable. Opposition was dealt with mercilessly (and as time went on by means of trial and execution) until by the early 1940s, he alone was still alive out of all the principal Bolshevik leaders of 1917. Stalin’s main quality was a recognition that the USSR would only survive if it developed its industrial capacity and economic growth within its own borders – ‘Socialism in one country’ – and that it had to do this quickly and at whatever cost to its population. This was achieved, we now know beyond any doubt, by forcing large numbers of people into slavery through unfounded criminalization, and by policies that seemed to be the very opposite of the Bolshevik ideals of Lenin and his comrades. The Soviet Constitution, redrawn in 1936, looked a model of rights and equalities, but offered nothing except hardship and even death to those who were deemed to have become enemies of the state – an easily gained status in the 1930s. At the time much of this was hidden from view and the USSR, with industrial growth and no unemployment whilst the rest of the developed world suffered depression and despair, seemed a beacon of hope to many, and offered continued attraction for the world’s Commu...