![]()

SECTION II

Killing and Combat Trauma: The Role of Killing in Psychiatric Casualties

Nations customarily measure the “costs of war” in dollars, lost production, or the number of soldiers killed or wounded. Rarely do military establishments attempt to measure the costs of war in terms of individual human suffering. Psychiatric breakdown remains one of the most costly items of war when expressed in human terms.

—Richard Gabriel

No More Heroes

![]()

Chapter One

The Nature of Psychiatric Casualties: The Psychological Price of War

Richard Gabriel tells us that “in every war in which American soldiers have fought in [the twentieth century], the chances of becoming a psychiatric casualty—of being debilitated for some period of time as a consequence of the stresses of military life—were greater than the chances of being killed by enemy fire.”

During World War II more than 800,000 men were classified 4-F (unfit for military service) due to psychiatric reasons. Despite this effort to weed out those mentally and emotionally unfit for combat, America’s armed forces lost an additional 504,000 men from the fighting effort because of psychiatric collapse—enough to man fifty divisions! At one point in World War II, psychiatric casualties were being discharged from the U.S. Army faster than new recruits were being drafted in.

In the brief 1973 Arab-Israeli War, almost a third of all Israeli casualties were due to psychiatric causes, and the same seems to have been true among the opposing Egyptian forces. In the 1982 incursion into Lebanon, Israeli psychiatric casualties were twice as high as the number of dead.

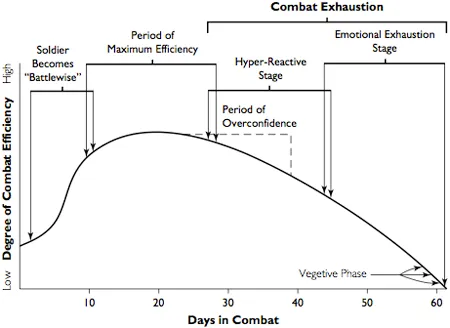

Swank and Marchand’s much-cited World War II study determined that after sixty days of continuous combat, 98 percent of all surviving soldiers will have become psychiatric casualties of one kind or another. Swank and Marchand also found a common trait among the 2 percent who are able to endure sustained combat: a predisposition toward “aggressive psychopathic personalities.”

The Relation of Stress and the Development of Combat Exhaustion to the Combat Efficiency of the Average Soldier

Source: Swank and Marchand, 1946

The British in World War I believed that their soldiers were good for several hundred days before inevitably becoming a psychiatric casualty. But this was made possible only by the British policy of rotating men out of combat for four days of rest after approximately twelve days of combat, as opposed to America’s World War II policy of leaving soldiers in combat for up to eighty days at a stretch.

It is interesting to note that spending months of continuous exposure to the stresses of combat is a phenomenon found only on the battlefields of the twentieth century. Even the years’ long sieges of previous centuries provided ample respites from combat, largely due to limitations of artillery and tactics. The actual times of personal risk were seldom more than a few hours in duration. Some psychiatric casualties have always been associated with war, but it was only in the twentieth century that our physical and logistical capability to sustain combat outstripped our psychological capacity to endure it.

The Manifestations of Psychiatric Casualties

In his book No More Heroes Richard Gabriel examines the many historical symptoms and manifestations of psychiatric casualties.[1] Among these are fatigue cases, confusional states, conversion hysteria, anxiety states, obsessional and compulsive states, and character disorders.

Fatigue Cases

This state of physical and mental exhaustion is one of the earliest symptoms. Increasingly unsociable and overly irritable, the soldier loses interest in all activities with comrades and seeks to avoid any responsibility or activity involving physical or mental effort. He becomes prone to crying fits or fits of extreme anxiety or terror. There will also be such somatic symptoms as hypersensitivity to sound, increased sweating, and palpitations. Such fatigue cases set the stage for further and more complete collapse. If the soldier is forced to remain in combat, such collapse becomes inevitable; the only real cure is evacuation and rest.

Confusional States

Fatigue can quickly shift into the psychotic dissociation from reality that marks confusional states. Usually, the soldier no longer knows who he is or where he is. Unable to deal with his environment, he has mentally removed himself from it. Symptoms include delirium, psychotic dissociation, and manic-depressive mood swings. One often noted response is Ganzer syndrome, in which the soldier will begin to make jokes, act silly, and otherwise try to ward off the horror with humor and the ridiculous.

The degree of affliction in confusional states can range from the merely neurotic to the overtly psychotic. The sense of humor exhibited in the movie and television series M*A*S*H is an excellent example of individuals mildly afflicted with Ganzer syndrome. And this personal narrative provides a look at a man severely afflicted with Ganzer syndrome:

“Get that thing out of my face, Hunter, or I’ll feed it to you with hot sauce.”

“C’mon, Sarge, don’t you want to shake hands with ‘Herbert’?”

“Hunter, you’re f’ed up. Anybody who’d bring back a gook arm is sick. Anybody who’d bring one in the tent is begging for extra guard. You don’t know where that thing’s been. QUIT PICKING YOUR NOSE WITH IT! OUT, HUNTER! OUT!”

“Aw, Sarge, ‘Herbert’ just wants to make friends. He’s lonely without his old friends, ‘Mr. Foot’ and ‘Mr. Ballbag.’ ”

“Double guard tonight, Hunter, and all week. Goodbye, sicko. Enjoy your guard.”

“Say good night to ‘Herbert,’ everyone.”

“OUT! OUT!”

Black humor of course. Hard laughs for the hard guys. After a time, nothing was sacred. If Mom could only see what her little boy was playing with now.

Or what they were paying him to do.

—W. Norris

“Rhodesia Fireforce Commandos”

Conversion Hysteria

Conversion hysteria can occur traumatically during combat or post-traumatically, years later. Conversion hysteria can manifest itself as an inability to know where one is or to function at all, often accompanied by aimless wandering around the battlefield with complete disregard for evident dangers. Upon occasion the soldier becomes amnesiatic, blocking out large parts of his memory. Often, hysteria degenerates into convulsive attacks in which the soldier rolls into the fetal position and begins to shake violently.

Gabriel notes that during both world wars cases of contractive paralysis of the arm were quite common, and usually the arm used to pull the trigger was the one that became paralyzed. A soldier may become hysterical after being knocked out by a concussion, after receiving a minor nondebilitating wound, or after experiencing a near miss. Hysteria can also show up after a wounded soldier has been evacuated to a hospital or rear area. Once he is there, hysteria can begin to emerge, most often as a defense against returning to fight. Whatever the physical manifestation, it is always the mind that produces the symptoms, in order to escape or avoid the horror of combat.

Anxiety States

These states are characterized by feelings of total weariness and tenseness that cannot be relieved by sleep or rest, degenerating into an inability to concentrate. When he can sleep, the soldier is often awakened by terrible nightmares. Ultimately the soldier becomes obsessed with death and the fear that he will fail or that the men in his unit will discover that he is a coward. Generalized anxiety can easily slip into complete hysteria. Frequently anxiety is accompanied by shortness of breath, weakness, pain, blurred vision, giddiness, vasomotor abnormalities, and fainting.

Another reaction, which is commonly seen in Vietnam veterans suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), years after combat, is emotional hypertension, in which the soldier’s blood pressure rises dramatically with all the accompanying symptoms of sweating, nervousness, and so on.[2]

Obsessional and Compulsive States

These states are similar to conversion hysteria, except that here the soldier realizes the morbid nature of his symptoms and that his fears are at their root. Even so, his tremors, palpitations, stammers, tics, and so on cannot be controlled. Eventually the soldier is likely to take refuge in some type of hysterical reaction that allows him to escape psychic responsibility for his physical symptoms.

Character Disorders

Character disorders include obsessional traits in which the soldier becomes fixated on certain actions or things; paranoid trends accompanied by irascibility, depression, and anxiety, often taking on the tone of threats to his safety; schizoid trends leading to hypersensitivity and isolation; epileptoid character reactions accompanied by periodic rages; the development of extreme dramatic religiosity; and finally degeneration into a psychotic personality. What has happened to the soldier is an altering of his fundamental personality.

These are only some of the possible symptoms of psychiatric casualties in war. Gabriel notes that “The mind has shown itself infinitely capable of bringing about any number of combinations of symptoms and then, to make matters worse, burying them deep in the soldier’s psyche so that even the overt manifestations become symptoms of deeper symptoms of even deeper underlying causes.” The key understanding to take away from this litany of mental illness is that within a few months of sustained combat some symptoms of stress will develop in almost all participating soldiers.

Treating the Mentally Maimed

Treatment for these many manifestations of combat stress involves simply removing the soldier from the combat environment. Until the post-Vietnam era, when hundreds of thousands of PTSD cases appeared, this was the only treatment believed necessary to permit the soldier to return to a normal life. But the problem is that the military does not want to simply return the psychiatric casualty to normal life, it wants to return him to combat! And he is understandably reluctant to go.

The evacuation syndrome is the paradox of combat psychiatry. A nation must care for its psychiatric casualties, since they are of no value on the battlefield—indeed, their presence in combat can have a negative impact on the morale of other soldiers—and they can still be used again as valuable seasoned replacements once they’ve recovered from combat stress. But if soldiers begin to realize that insane soldiers are being evacuated, the number of psychiatric casualties will increase dramatically. An obvious solution to this problem is to rotate troops out of battle for periodic rest and recuperation—this is standard policy in most Western armies—but this is not always possible in combat.

Proximity—or forward treatment—and expectancy are the principles developed to overcome the paradox of evacuation syndrome. These concepts, which have proved themselves quite effective since World War I, involve (1) treatment of the psychiatric casualty as far forward on the battlefield as possible—that is, in the closest possible proximity to the battlefield, often still inside enemy artillery range—and (2) constant communication to the casualty by leadership and medical personnel of their expectancy that he will be rejoining his comrades in the front line as soon as possible. These two factors permit the psychiatric casualty to get treatment and much-needed rest, while not giving a message to still-healthy comrades that psychiatric casualty is a ticket off the battlefield.

![]()

Chapter Two

The Reign of Fear

If I had time and anything like your ability to study war, I think I should concentrate almost entirely on the “actualities of war”—the effects of tiredness, hunger, fear, lack of sleep, weather…. The principles of strategy and tactics, and the logistics of war are really absurdly simple: it is the actualities that make war so complicated and so difficult, and are usually so neglected by historians.

—Field Marshal Lord Wavell, in a letter to Liddell Hart

What goes on in the mind of a soldier in combat? What are the emotional reactions and underlying processes that cause the vast majority of those who survive sustained combat to ultimately slip into insanity?

Let us use a model as a framework for the understanding and study of psychiatric casualty causation, a metaphorical model representing and integrating the factors of fear, exhaustion, guilt and horror, hate, fortitude, and killing. Each of these factors will be examined and then integra...