![]()

CHAPTER X

MYTH OF THE HOUSE OF OEDIPUS

SOPHOCLES’ TRAGEDIES: OEDIPUS THE KING, OEDIPUS AT COLONUS, AND ANTIGONE

OEDIPUS THE KING

AMONG THE APPROXIMATELY 200 GREEK TRAGEDIES THAT HAVE SURVIVED UNTIL TODAY, ONLY ONE TRUE TRILOGY EXISTS — THE ORESTEIA BY AESCHYLUS.

It consists of three plays written in chronological order with a single narrative thread.

The Oedipus plays of Sophocles, sometimes called the Oedipus trilogy or the Theban trilogy, are not a trilogy. Sophocles’ three plays were not written or staged at the same time. Antigone was probably staged around 442 BC; Oedipus the King – 13 years later, about 429; and Oedipus at Colonus probably in 401, five years after Sophocles died and some 40 years after he wrote Antigone.

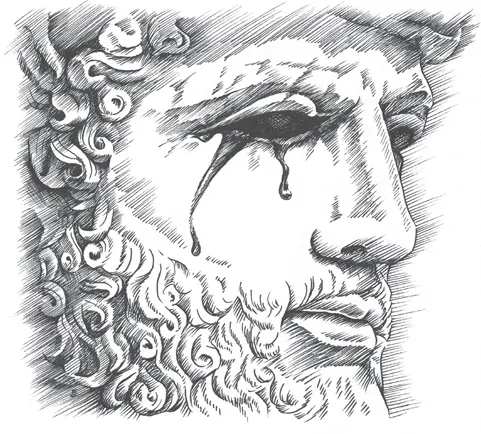

BLIND OEDIPUS wandered for many years in exile, banished from Thebes because of his sin. He was an abject beggar, a wreck of a man. Blind and frail, he walked with the help of his daughter Antigone.

We will not discuss these plays in the order in which they were written, but rather in the order of Sophocles’ overall storyline – Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone. We’ll also treat them as three distinct plays that happen to contain the same major characters. Since the three do not express a single narrative thread, the actions of the players are sometimes inconsistent from play to play.

PATTERN OF SOPHOCLEAN TRAGIC HERO

Sophocles’ plays are different in another way from the trilogy of Aeschylus. More so than Aeschylus, Sophocles concentrates his attention on an individual. The protagonist is isolated, apart, alone, and facing a terrible struggle or problem.

One critic, Bernard Knox, said that Sophocles invented the tragic hero, that is, the hero as main character of a tragedy, to describe the protagonists of his plays. Oedipus is the kind of tragic hero we see later in Hamlet and is of a different sort than the heroes found in Homeric epics.

These three plays, like most of Sophocles’ extant plays, take their names from their main characters – Oedipus and Antigone. Although the circumstances differ, they fit the same basic pattern.

The protagonist is faced with a crisis. He or she can only avert disaster by agreeing to a compromise that would betray something he or she holds to be supremely important. The protagonist refuses to compromise, despite persuasive speeches, threats, or violence – or all three. The protagonist remains steadfast in his or her refusal to compromise. The end result is his or her destruction.

Other characters, or the chorus, refer to the protagonists of these plays as being deinos. Deinos is an ambiguous Greek word meaning – all at once – wondrous and awe-inspiring, terrible and frightening, or just simply strange. A deinos protagonist is frequently set alongside another character who is more like a normal human being. That brings out their implacable nature and essential oddity by comparison. These characters are not cuddly, friendly, affectionate people. Rather, they are both repellent and admirable.

Another noteworthy characteristic, typical of Sophoclean tragedy, is that the gods do not appear in the Oedipus plays. Instead, the characters must determine the will of the gods by interpreting inherently ambiguous omens and prophecies. This lack of help from the gods underscores the isolation of the Sophoclean hero. He cannot turn to the gods for help.

Let’s turn now to Sophocles’ Oedipus the King.

MYTH OF OEDIPUS THE KING

In the basic myth, Oedipus is the baby son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of Thebes. An oracle has told them that Jocasta’s forthcoming son will grow up to kill his father and marry his mother. To prevent that terrible fate, Laius and Jocasta leave the baby out in the countryside to die shortly after he is born (this was an acceptable practice in that time and place). However, the infant is rescued and brought up by someone else. He doesn’t know who his true parents are and thus grows up unaware of his true identity.

In the next part of the myth, the now grown infant, who has been named Oedipus by his adoptive parents, returns to his native town of Thebes. These days, a part-human, part-animal monster named the Sphinx has been terrorizing the citizens of Thebes. She requires each person to answer a riddle. If they cannot answer the riddle, she kills them. Oedipus overcomes the Sphinx by answering her riddle.

The people of Thebes are grateful to Oedipus for freeing them from the Sphinx, and so they make him their king. He replaces their old king, Laius, who has recently been killed. In addition to awarding the kingship of Thebes to Oedipus, the Thebans also offer him the hand of the queen of Thebes in marriage. The queen of Thebes, of course, is none other than Jocasta, his real mother, although nobody knows it, least of all Oedipus.

In the last part of the myth, Oedipus rules Thebes for several years. He is ignorant of what he has done. He and Jocasta have four children. The whole truth is not discovered until after these children are born. The old king, Laius, died because Oedipus killed him without knowing who he was. And now Oedipus is married to, and has had children with, his own mother. When the truth finally comes out, Jocasta kills herself. Oedipus immediately blinds himself and goes into exile from Thebes.

SOPHOCLES ADDS DETAILS TO THE MYTHS

That is the basic myth of Oedipus. However, Sophocles added a few telling details of his own. First, in the Sophoclean version, Jocasta gives the infant Oedipus to a trusted slave, a shepherd, and asks the slave to abandon the baby in the wilderness.

But, instead of leaving the baby on the ground to die, the shepherd hands the baby over to a Corinthian shepherd who pastures his flocks on the same mountain. The Corinthian shepherd knows that the king and queen of Corinth, Polybus and Merope, are childless, and so he takes the baby to them. Oedipus is thus raised as a prince of Corinth, and believes that Polybus and Merope are his true parents.

Here’s another detail added by Sophocles. When Oedipus becomes a young man, a guest at a banquet taunts him by saying, “You are not really Polybus’ son; nobody knows who you are.”

This greatly disturbs Oedipus. So he travels to Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi and asks, “Am I the son of Polybus and Merope?”

But the Oracle does not answer the question. The Oracle says only, “You will kill your father and marry your mother.” Oedipus promptly leaves Corinth, never to return, in order to avoid killing his parents. Oedipus heads toward Thebes.

On the road to Thebes, Oedipus meets, quarrels with, and kills an old man at a crossroads. The old man happens to be Laius, his true father, although Oedipus does not learn this until much later.

When Oedipus arrives in Thebes, he discovers that the Theban King Laius has been recently killed. However, the one eyewitness to Laius’ murder swears that Laius was killed by a band of robbers. And so no one, neither Oedipus nor anyone else, immediately connects the old man Oedipus has killed and King Laius, who has been killed by a band of robbers. Because Laius is dead, and because Oedipus has solved the riddle of the Sphinx, he is given the kingship of Thebes and Jocasta’s hand in marriage.

In the play, the truth of what actually has happened, and who Oedipus actually is, emerges in fragmented, non-chronological order. Oedipus violates two of the most formidable taboos of almost every human society. But Sophocles does not focus specifically on those actions – neither the murder of Oedipus’ father Laius, nor the incest with his mother Jocasta.

Instead, Sophocles focuses on the moment Oedipus discovers the truth. This discovery occurs neither by divine intervention nor by chance. Rather, Oedipus’ determination to know his own origins combines with his own persistent, courageous actions to lead to his discovery of the truth. The hero of the play is thus his own destroyer. He is the detective who tracks down and identifies the criminal – who turns out to be himself.

AS OEDIPUS THE KING OPENS...

With that as mythic background, let’s turn to the play itself. As it opens, Oedipus is in his full regal role as head of state, dedicated to the interests and needs of Thebes. He enforces the law. He investigates, prosecutes, and judges criminals. In all these respects, Oedipus personifies triumphant human progress — from primitive barbarism to the highest civilization of the city-state – the notion first introduced in the Oresteia of Aeschylus.

The play begins with the words of a priest, who is accompanied by the chorus of Theban citizens. They beg Oedipus to find a cure for a terrible plague that ravages the city. Oedipus has already sent his brother-in-law Creon to learn the cause of the plague from the Delphic Oracle. Creon returns and reports that pollution is on the land because the murderer of Laius is still living, unknown, in Thebes. Oedipus responds by invoking a solemn, formal curse against the murderer of Laius. He says:

I order you, every citizen of the state

where I hold throne and power: banish this man –

whoever he may be – never shelter him, never

speak a word to him, never make him partner

to your prayers, your victims burned to the gods….

He is the plague, the heart of our corruption….

And then he finishes:

I curse myself as well… if by any chance

he proves to be an intimate of our house,

here at my hearth, with my full knowledge,

may the curse I just called down on him strike me!

— Oedipus the King, Lines 269-287. Robert Fagles translation.

This is the first of many highly ironic speeches by Oedipus. He just cursed himself without knowing that he cursed himself. He also clearly and accurately states his own position – he is the plague and corruptor of his own land.

“YOU ARE THE LAND’S POLLUTION” — TIRESIAS

He then summons the seer Tiresias to identify the murderer. Tiresias is obviously reluctant to do so. This arouses Oedipus’ anger and suspicion. He thinks the seer is being unhelpful because he cares nothing about Thebes. Or maybe, he thinks, Tiresias helped plot the murder of Laius.

Oedipus’ anger enrages Tiresias in turn. The prophet tells Oedipus, “You are the land’s pollution.”

Oedipus now thinks Tiresias is simply trying to taunt and slander him, because he knows that he cannot be Laius’ murderer. Laius was murdered by many men, not by one.

Oedipus next directly accuses Creon of treachery. Then Jocasta steps forward to help calm Oedipus and ease the quarrel. Jocasta says, in part, that oracles can safely be disregarded, and that we don’t need to pay attention to this one. As she speaks, she mentions a crucial piece of information that no one had disclosed or heard before. She says:

An oracle came to Laius one fine day …and it declared that doom would strike him down at the hands of a son, our son, to be born of our own flesh and blood. But Laius, so the report goes at least, was killed by strangers, thieves, at a place where three roads meet… my son – he wasn’t three days old and the boy’s father fastened his ankles, had a henchman fling him away on a barren, trackless mountain….

Apollo brought neither thing to pass…

That’s how the seers and all their revelations mapped out the future. Brush them from your mind.

— Oedipus the King, Lines 784-800. Robert Fagles translation.

The one crucial bit of information that Jocasta let slip, the one thing no one has ever said to Oedipus before, is that Laius was killed at a place where three roads meet. Oedipus knows that he killed an old man right before he came to Thebes, at a place where three roads meet.

To Jocasta’s story, Oedipus reacts with absolute horror. Speaking of the man he killed he says:

Oh, but if there is any blood-tie between Laius and this stranger... what man alive more miserable than I? More hated by the gods? I am the man... And all these curses I – no one but I brought down these piling curses on myself!... Wasn’t I born for torment? Look me in the eyes!

I am abomination – heart and soul!

— Oedipus the King, Lines 899-911. Robert Fagles translation.

At this point, Oedipus suspects only that the old man he killed might have been Laius. He has no inkling yet of the full horror that awaits him, and so he persists in learning the truth, whatever it may be.

OEDIPUS QUESTIONS EYEWITNESSES

Oedipus sends for the witness to Laius’ death, to question him. While we wait for him to arrive, a messenger comes from Corinth to tell Oedipus t...