![]()

1

From the Simon to the BlackBerry

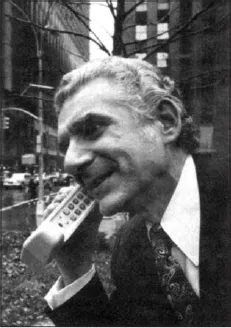

Martin Cooper with Motorola’s DynaTac prototype in 1973 (Martin Cooper)

On April 3, 1973, Martin Cooper dialed his way into history. As the general manager of Motorola’s systems division, he had flown to New York City to unveil a prototype of the world’s first handheld cellphone. The 28-ounce phone, which had a long antenna, a thin body, and a protruding bottom “lip,” making it resemble a boot, isn’t sleek by current standards, but it was revolutionary. Until 1973 a mobile phone required so much power it had to be tethered to a car’s electrical system or an attaché case containing a huge battery. The phone that Cooper and his team had developed—the DynaTAC—fit right in the palm of his hand.

Reporters had gathered at the Hilton hotel in Midtown Manhattan to see the new phone. Cooper was nervous. “There were thousands of parts in the thing; it was hard to keep it running,” he recalls. “We had people at the hotel still working at midnight [the night before] to make sure the phone would be able to make calls.”1 Cooper got lucky. The phone functioned flawlessly that day, both before the press conference when he placed a call from the bustling street in front of a reporter, and later at the event, where he made a number of calls, even letting one young journalist dial her mother in Australia. “At that time, not everyone in the world thought people needed cellphones,” he said, “but the reporters were quite enthusiastic.” Today Cooper is universally acknowledged as the creator of the cellphone and the first person to make a cellphone call in public. His story gave the world a straightforward starting point for understanding cellphone history.

In contrast, there is no consensus on the smartphone’s origins. A number of people think it was born in 2007, when Apple cofounder Steve Jobs proudly showed off the first iPhone at the Macworld conference in San Francisco. But what many people either forget or do not know is that phones with smartphone features had already been on sale for more than a decade.

Some experts believe smartphones emerged from cellphones when manufacturers began squeezing sophisticated programs and Web-browsing features into their handsets. Others say personal digital assistants (PDA), with their touchscreens and open operating systems, were the real progenitors of the smartphone. A third camp thinks pagers and messaging devices, including early BlackBerrys, paved the way by introducing mobile data and e-mail to a broad audience.

The question hangs on how you define a smartphone. Generally speaking, a smartphone distinguishes itself from a cellphone by running on an open operating system that can host applications (apps) written by outside developers. The apps expand the phone’s functionality, giving it computerlike capabilities, and can be downloaded and installed by users, not just pre-installed by smartphone companies. Smartphones also have a number of built-in features that basic phones typically do not, including touchscreens that can sense multiple-finger swipes, high-definition displays, fully Internet-capable browsers, advanced software that automatically grabs new e-mails, and high-quality cameras, music, and video players.

It took more than a decade to cram all these features into one handheld device. The earliest smartphones came from IBM, Nokia, Ericsson, Palm, and Research In Motion/BlackBerry. Though these phones pushed boundaries in the 1990s and early 2000s, they were all limited in some way, especially in their Internet and app access. Most of these early smartphones were not sales hits. Some were famous flops. But all contributed to the smartphones we now carry in our pockets, whether they are iPhones, Android phones, Windows Phones, or BlackBerrys.

IBM AND THE SIMON

IBM’s Simon phone was born of twin desires: a talented engineer’s to tackle the challenge of creating a portable, wirelessly connected computing device and IBM’s to burnish its image by unveiling never before seen, futuristic gadgets. Though the Simon was commercially available for less than a year, many regard it as the world’s first smartphone.

Frank J. Canova Jr. was the gutsy engineer behind the Simon. Gary Wisgo, who was Canova’s engineering manager at IBM, says Canova had two rare abilities. In an industry known for its narrow specializations, Canova was skilled at both hardware and software. He also had a knack for seeing the future. “A lot of engineers just sit and design circuits; a lot of programmers just sit and design programs,” says Wisgo. “Frank would look out at the industry, see what other companies were doing, and say, ‘We should do this.’”

The early 1990s were a fertile time for dreaming up portable, wireless gizmos. Advances in microprocessor chips and other components made it possible to shrink computers into mobile devices. PCMCIA cards—credit card–sized “personal computer memory cards” that could expand a computer’s storage or functionality—were sparking new ideas about computing capabilities. Cellular service was expanding across the country. And carriers were planning network upgrades that would make it easier to send and receive data on mobile devices.

Anticipating a lucrative new market, technology companies started concocting next-generation computing products. Apple was stealthily developing its Newton PDA and had publicly confessed an interest in wireless devices. AT&T was funding a start-up to create the EO, a PDA-tablet hybrid with a built-in cellular modem. IBM, which had produced PCs for a decade, was also investigating computer miniaturization and wireless connectivity, in its research lab in Boca Raton, Florida.

Canova worked in that lab as a senior technical staff member on IBM’s advanced technology team. In mid-1992, the 35-year-old was experimenting with touch-sensitive glass panels that snapped onto the front of computer monitors. He decided to try making a touchscreen version of a phone keypad, using a computer monitor, a glass touchscreen overlay, and Microsoft’s Visual Basic computer programming language. Within a few days Canova had a touch-responsive mock-up of the keypad—and a plan. He started talking to IBM management about creating a touchscreen handheld device that would combine calling and computing features.

IBM was game. It had recently kicked off a corporate initiative called Vision 95, which aimed to predict what computers, electronics, and computing services would look like in 1995. As part of the initiative, Jerry Merckel, an IBM manager who specialized in strategic planning, commissioned sleek wood-and-plastic models of Canova’s phone concept and a set of matching PCMCIA cards. Dubbing it “tomorrow’s computer,” he explained how the cards would transform the phone into a camera, or a music player or game player. Intrigued, Paul Mugge, who was an IBM vice president and the general manager of the Boca Raton office, approved funding.

Model PCMCIA cards used in internal IBM presentations to obtain funding for the Simon project. Inserting the cards would expand the phone’s functionality by adding GPS, camera, TV, and radio capabilities. (Jerry Merckel)

Canova set about designing a device that would be a phone first and a computer second. “We wanted using it to be natural, like a [landline] phone, where you just lift the handset and dial numbers,” he explains. “Unlike a computer, you wouldn’t have to boot it or configure it.” The phone’s touchscreen design supported that ethos. Because touchscreens are thinner than built-in keyboards, users would be able to operate the device with one hand, like a regular phone. While tinkering with the touchscreen, Canova came to another realization: the phone’s menu should be arranged like a computer’s, with small icons for launching applications.

When IBM management saw Canova’s touchscreen demos, they decided to include the phone in the company’s technology showcase at the upcoming 1992 Computer Dealers’ Exhibition (COMDEX)—then the computer industry’s largest trade show, which was held in Las Vegas each November. IBM’s mainframe business was collapsing, because its corporate clients were shifting their computing to lower-cost personal computers, and the company wanted to portray at least a portion of the company as still vibrant.

The phone project became a five-person effort. Wisgo says he was the manager, but Canova was the visionary. Wisgo’s team had just 14 weeks to transform Canova’s lab work into a prototype for COMDEX. The phone could make calls using a radio module IBM had sourced from Motorola, but the team still had to design the circuit board and find manufacturers for the touchscreen and battery. “Half of the device was in my mind; the other half was in pieces, splayed on a bench,” Canova remembers. Writing software to support the phone’s various functions was the most demanding task. Besides making calls, the phone needed to be able to send and receive e-mails, store the user’s calendar and address book, and host a calculator. Users also needed to be able to move fluidly between the different features by switching screens—an early version of mobile multitasking. The team worked 80-hour weeks to meet the deadline. “We lived at the lab day and night,” says Wisgo. “It was one of the most trying periods in my life.” Canova, who was a new father, brought his infant son to the lab on weekends so he could squeeze in time with him.

Glitches with the phone’s code continued right up to COMDEX. “People would ask, ‘Should we pull it?’ and I’d say, ‘Keep going,’” Mugge remembers. “We didn’t have a backup plan.” The team pressed on. On the first day of the trade show, after successfully demonstrating the phone’s calling and e-mail features, attendees mobbed the IBM booth to get a closer look at the device. That week, USA Today published two articles highlighting the phone. The first marveled at the speed with which IBM developed the device. The second featured a photo of Canova holding it and described IBM’s COMDEX demo as “seemingly flawless.”2

Encouraged by the media attention, IBM agreed to fund the creation of a real product, and soon after, the Atlanta-based carrier BellSouth expressed interest in carrying it. IBM had been calling it a “personal communicator,” but BellSouth named the phone Simon, after the children’s game Simon Says and the electronic memory game that was popular in the late 1970s and 1980s. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, BellSouth’s marketing managers thought the name “evoked simplicity” and would be easy for consumers to remember.3

IBM Simon (Wikimedia)

Targeting an April 1994 release, IBM’s Simon team swelled from 5 people to more than 30. Taking the phone from a prototype to a real product was challenging. Motorola refused to supply the phone’s radios, explaining it would be “counterstrategic” for them to help IBM build a commercial smartphone, according to Wisgo. IBM got a replacement part from Mitsubishi, the Japanese electronics manufacturer, but the swap delayed the entire project.

The Simon team also wrestled with the phone’s size and battery. The brick-shaped device ended up measuring 8 inches by 2.5 inches by 1.5 inches and weighing 18 ounces. “It was clunky, and we knew it, but we couldn’t get it any smaller at the time,” says Canova. Battery life was the single toughest issue. It topped out at an hour of talk time or eight hours of standby time, so IBM provided BellSouth with a thicker, double-capacity battery to sell separately. “We could have put a huge battery on [the Simon], but no one would have bought it,” explains Wisgo. “It was too big already.”

The Simon launched four months later than planned, at a price of $899. It boasted an advanced set of features. It supported multiple forms of communication: calls, e-mail, faxes, and pager messages. It had a “graphical user interface,” meaning it was image- and icon-based. To navigate between phone, fax, and calendar functions, users simply touched the appropriate icons on the touchscreen, and they could customize their phones’ features and functions by inserting different PCMCIA cards, similar to the way apps expand smartphone functionality today. The phone even included password protection, a note pad feature that saved typed memos, a world clock, and a puzzle-piece game called Scrabble®.

These features have since become commonplace in smartphones, but in the early 1990s they were unusual and, to some people, intimidating. BellSouth tried to counteract confusion by advertising the Simon as “Mobile Communications Made Simple,”4 but news articles described the phone as everything from a portable computer to a “processor-based telephone”5 to an “enhanced telephone and messaging unit.”6 Reviews tended to commend the phone’s advanced features without advising people to buy it. PC Magazine said the Simon was “an impressive feat of integration” but cautioned that “while Simon is definitely much more than...