eBook - ePub

The Changing Scottish Landscape

1500-1800

Ian Whyte, Kathleen Whyte

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 264 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

The Changing Scottish Landscape

1500-1800

Ian Whyte, Kathleen Whyte

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Originally published in 1991 and focussing on the countryside, this book examines patterns of settlement and agriculture in Scotland and considers how these were increasingly altered during the 17th and 18th Centuries by the first Improvers and then by the more widespread impact of the Agricultural Revolution. It considers the effect on the landscape of the changing role of the church, the development of improved communications and the rise of new industries. The book analyses in detail the ways in which the landscape changed in Scotland's transition from a medieval, impoverished country and an undeveloped economy to a modern society and one of the most highly urbanised countries in Europe.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

The Changing Scottish Landscape è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a The Changing Scottish Landscape di Ian Whyte, Kathleen Whyte in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Histoire e Histoire de l'Écosse. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1

Rural settlement before the improvers

The rural settlement pattern is a fundamental aspect of the pre-improvement Scottish landscape. The problem is that we still know very little about it in either the Highlands or the Lowlands before the mid-eighteenth century when detailed estate plans first become available in quantity. The lack of cartographic evidence for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the limitations of documentary sources, make it difficult to establish the character of settlement in 1500, and how this had evolved from medieval times.

Another difficulty is that few medieval and post-medieval settlement sites have been excavated in Scotland. In England excavations at a number of deserted villages, notably the long-continued dig at Wharram Percy, have added greatly to our understanding of the construction of late-medieval peasant houses and how the settlements they made up evolved. In Scotland excavation has focused on prehistoric and Roman sites rather than those from later times. A further problem is that excavated medieval and post-medieval sites have often provided few artefacts making accurate dating impossible in some cases. In addition there has been a lack of field surveys of the surface remains of deserted sites although the position has improved in recent years with detailed work in areas as far apart as Caithness and the Borders.

The settlement pattern immediately preceding the period of rapid improvement and change in the later eighteenth century is recoverable in the Lowlands from estate plans and in many parts of the Highlands from abundant remains on the ground. There has been a natural, but dangerous, tendency to look at settlement in this late period and project its features back into the more poorly documented medieval period. This has been particularly true of the Highlands whose wealth of deserted settlements from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries deserves more detailed study than it has received. The remains are as widespread, and far better preserved, than those of deserted medieval villages in England. However, as we will show, such settlements belong to a short-lived phase which was demonstrably uncharacteristic of earlier centuries.

Because most of the pre-improvement settlement pattern has been wiped out in the Lowlands due to subsequent intensive exploitation of the land, deserted settlement sites generally occur on the fringes of improved land, often in marginal semi-upland locations. Such sites may not have been representative of those in the Lowlands which have been obliterated.

Dispersed settlement: ferm toun and clachan

The rural settlement pattern of Scotland between the sixteenth and later eighteenth centuries was mainly a dispersed one of small hamlets and isolated dwellings. It had many similarities with other outlying areas of north-west Europe such as Ireland, Wales, south-west England and Brittany. It was well adapted to conditions where extensive areas of freely drained fertile soil, capable of supporting large communities, were infrequent and to an economy oriented towards livestock rearing. Nevertheless, the fact that the same basic settlement pattern occurs in districts like Strathmore, which have large areas of high-quality land, and are known to have concentrated on arable farming in the pre-improvement period, should make us wary of being too deterministic about the development of this dispersed settlement pattern. There must also have been powerful influences within Scottish rural society which prevented the development of larger villages in such areas.

The origins of this settlement pattern are hard to determine. In other areas of hamlets and farmsteads, like south-west England, prehistoric roots for it have been suggested. It is likely that the basic frameworks of the settlement pattern that existed in Scotland in 1500 go back to pre-medieval times. The standard settlement unit was the hamlet cluster or ‘ferm toun’ as it was known in the Lowlands. The equivalent term in Gaelic was ‘baile’. In a Highland context the name ‘clachan’ has also been applied to this type of settlement. Although clachans were, strictly speaking, places possessing a church or chapel the label has been used more generally by archaeologists and geographers to describe all Highland hamlets, similar to its usage in Ireland.

The ferm toun has usually been portrayed as a cluster of between six and a dozen households, mainly tenants working a joint farm. Contemporary estate plans and surviving deserted settlements show that the buildings comprising most ferm touns were loosely scattered or strung out in an irregular line without any sign of planning. This was partly due to the fact that before the later eighteenth century most dwellings in such settlements were flimsily constructed. Rebuilding on adjacent sites was frequent. The positions of houses and outbuildings tended to move over time as a result. An English traveller in the Highlands in the early eighteenth century described the buildings in the settlements he visited as ‘all irregularly placed, some one way some another’, a description that would fit most hamlet clusters, Highland or Lowland. As well as being fluid in layout the actual locations of ferm touns and clachans could change too, as we shall see presently.

Some ferm touns had a semblance of regularity where their dwellings were built along a slope with the same general alignment. Certain deserted hamlets in the south-west Highlands, and the excavated example from Lix in Perthshire which will be described below, had a more planned linear layout. There is a close association between such sites and estates of landowners like the dukes of Argyll where agricultural improvement began relatively early in the mid-eighteenth century. These more regimented clusters probably represent a preliminary phase of rationalisation before the clachans were cleared and abandoned.

The social composition of the ferm toun could vary. In its ideal form it comprised a joint farm worked by several tenants holding equal shares. However, hamlets might also contain cottars. These were smallholders who sublet portions of the arable land from the principal tenants in return for providing labour. In deserted Highland clachans the cottars’ dwellings can sometimes be distinguished from those of the tenants. They were smaller, lacking attached byres and barns, and were often more poorly built. Some touns consisted of a large consolidated farm worked by a single prosperous tenant with the aid of several cottars. Others were exclusively inhabited by cottars. ‘Cottoun of X’ is a common type of place name and as most cottars also had a part-time trade such as weaving or shoemaking, these touns acted as minor service centres for the local population.

Pre-improvement ferm touns and clachans have not survived in the modern settlement pattern in any numbers. The amalgamation of holdings and farms from the seventeenth century has replaced them by the consolidated single farms which are prominent in the modern landscape throughout the Lowlands as well as in the southern and eastern Highlands. However, some impression of their character can be gained from two examples which have survived with relatively little change. Swanston stands on the outskirts of Edinburgh at the edge of the Pentland Hills. Its old cottages, thatched, whitewashed, and possibly dating back to the seventeenth century, are laid out around a small green with a later school and farmstead. Auchindrain, in mid-Argyll on the road from Inveraray to Lochgilphead, is a Highland clachan which, almost uniquely, has survived into modern times. Appropriately it now forms a museum of rural life. In 1800 it was a classic hamlet cluster with twelve tenants paying rent to the Duke of Argyll for shares in the farm. Unlike other joint farms in the area it escaped obliteration with the onset of improved agriculture and one house was inhabited until 1954. The site has twenty buildings including long houses with house and byre combined, barns and cottages. In between them are kailyards for vegetables, stackyards for the corn, enclosures and access ways. The interiors of some of the houses have been furnished to show what they were like in earlier times. Making allowances for the neatness of the site, it gives a good impression of how many Highland and the Lowland settlements must have appeared in earlier times.

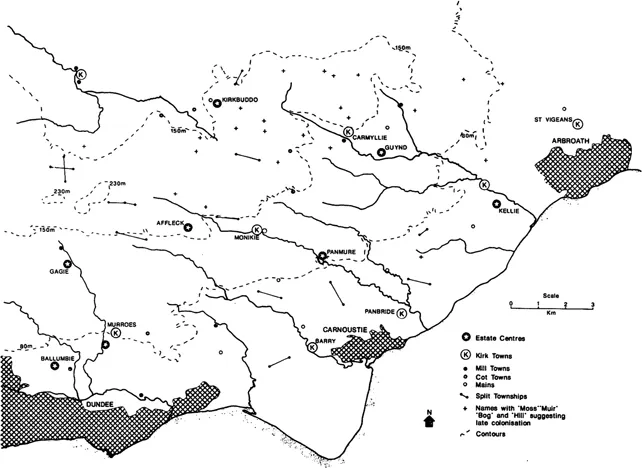

Many hamlets were merely ferm touns, purely agricultural in function, but larger settlement clusters also developed under the influence of various nucleating forces. In the Lowlands the parish church generally provided the focus for a larger hamlet, the kirk toun. In the Highlands such nucleations were rarer and it was more common for churches and chapels to stand in isolation. However, some kirk touns did exist and have retained their original character, like Kilmory in Kintyre (NR 702751). In the modern landscape many kirk touns have lost their original form. Some developed into small burghs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, others into planned villages in the eighteenth and nineteenth. Elsewhere kirk touns have been split up as a result of agricultural improvements or have declined because of the development of planned villages within their parish.

Nevertheless, kirk touns surviving as small, scattered hamlets can still be found in some areas. They have proved more durable than ordinary ferm touns and are probably the principal surviving element of the pre-improvement settlement pattern in the modern landscape. Their buildings, with the exception of the parish church, rarely predate the later eighteenth century but their size and layout have probably not changed very much. Some parish centres are still named ‘Kirkton of X’ and a glance at the Ordnance Survey map of areas like Aberdeenshire, Angus or Ayrshire will show that a substantial proportion of parish centres are still small hamlets loosely grouped around the church. There is a whole line of them along the well-drained slopes above the Carse of Gowrie on the northern side of the Firth of Tay. Today, as well as the kirk, you may find a post office and a hotel but rarely much more in the way of service facilities. Insufficient research has been carried out to see to what extent the layout of such kirk touns has changed from the eighteenth century, when many of them are recorded on estate plans, to the present day.

Other nucleating elements are emphasised by place names which recur again and again on the modern map; ‘bridgeton’ ‘castleton’, ‘chapelton’ and ‘milton’ are self-explanatory. Along the coast fisher touns reflected a distinctive way of life quite separate from that of neighbouring agricultural communities. They are particularly numerous in the north east from the coast of Angus to the Moray Firth. Most of them were developed between the sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth by landowners who wanted to increase their revenue and ensure local supplies of fish. They should not be confused with the planned fishing villages of the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which served the same purpose on a grander scale. These earlier fisher touns are usually laid out in one or more rows close to the shore, the houses built with their gables to the sea for protection from wind and weather. Pennan in Aberdeenshire (NJ 8465), or Crovie (NJ 8065) and Whitehills (NJ 6565) in Banffshire, are good examples.

‘Mains’ is another common place-name element in Lowland Scotland. The mains was the home farm of an estate, the descendant of the medieval demesne lands which were worked under the direct management of a feudal lord. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the mains was usually a large farm close to the landowner’s residence. It was sometimes leased to tenants but even in the early eighteenth century many proprietors still supervised the cultivation of the mains in person and retained traditional labour services to help work it. Tenants might be required, as a condition of their leases, to undertake a certain number of days’ work each year on the mains, ploughing, harrowing, sowing, harvesting and spreading manure. The castle or mansion with the mains and often an attached cottar toun frequently formed a substantial settlement in its own right.

Nucleated settlement: village and burgh

Most villages in the modern Scottish landscape did not exist in 1500. They are either small burghs of barony dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries or planned estate villages from the eighteenth and early nineteenth. However, one part of Scotland, the Lothians and the Merse, has many nucleated villages whose origins appear to go back to medieval times. In West Lothian industrial development has obscured much of this pattern of village settlement. Around Edinburgh former villages like Corstorphine and Duddingston have been absorbed by suburban expansion though they still preserve some of their original identity. The pattern of ancient villages is best seen in East Lothian and the Merse. There you can find villages laid out in rows or focusing on greens with the parish church, the market cross and sometimes the gates of the local ‘big house’ nearby in a style strongly reminiscent of north-east England.

The origins of this settlement pattern and the reasons for its distinctiveness are unclear. The names of many of the villages have Anglo-Saxon origins and this has prompted some historians to look to the Anglian occupation of the area between the seventh and ninth centuries as a period in which they might have been established. However, the idea of large numbers of Anglian migrants establishing villages and field systems on a class...