eBook - ePub

Competition for Scarce Groundwater in the Sana'a Plain, Yemen. A study of the incentive systems for urban and agricultural water use.

Mohammed I. Al-Hamdi

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 216 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Competition for Scarce Groundwater in the Sana'a Plain, Yemen. A study of the incentive systems for urban and agricultural water use.

Mohammed I. Al-Hamdi

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The efficient management of water supply becomes even more important in arid areas where supply is at best erratic. This book looks at a range of issues connected to urban and agricultural water use in the Sana'a Plain area, including engineering and logisical problems, environmental and climatic influences on groundwater, legal and political wrangles, economic considerations and options for waste water re-use.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Competition for Scarce Groundwater in the Sana'a Plain, Yemen. A study of the incentive systems for urban and agricultural water use. è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Competition for Scarce Groundwater in the Sana'a Plain, Yemen. A study of the incentive systems for urban and agricultural water use. di Mohammed I. Al-Hamdi in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Technologie et ingénierie e Agriculture. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Chapter 1

Introduction: The Supply of and Demand for Water Resources in the Sana’a Basin

1.1 Water availability and use in Yemen

1.1.1 Socio-economic background

The Republic of Yemen (ROY) was established on May 22, 1992, when the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) were reunified. The ROY is located at the south-southwest part of the Arabian Peninsula between 12° and 19° north of the equator and between 42° and 55° east of Greenwich. The topography of the country varies widely between sea level in the western and southern coastal plains to elevations of more than 3;700 meters above sea level (masl) in the northwest mountains of the country. Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, is situated in a large plain in the central highlands at 2,200 m altitude. Yemen covers a total area of around 536,000 (km)2 and consists of 19 governorates. The latest national population census (December 1994) showed a total population of 15,831,757 inhabitants, of whom 23.24% live in urban areas, and 0.97 million in Sana’a. The annual national population growth rate was reported at 3.7%, with an elevated rate of 8.9% in the urban areas, which is mostly attributed to internal migration from the rural areas. The population of Yemen has been projected to reach 20.3 and 23.4 million by the year 2005 and 2010, respectively (Central Bureau of Statistics, 1995; Van der Gun and Ahmed, 1995).

In 1990 the per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was estimated at 760 US$. Governmental services and agriculture dominate the economy of the country, with 21.4% and 20.6% shares in the GDP in 1990, respectively. Although agriculture contributed less to the GDP than the service sector, it employed around 60% of the national labor force (Van der Gun and Ahmed, 1995). In 1998, according to the World Bank (1999), the share of agriculture, industry, and services in the GDP in 1998 was 16.2%, 44.9% and 38.9% respectively. The GDP was estimated at 5.4 US$ billion, lowering the per capita GDP to around 300 US$, which is very low compared to the average of 2,025 US$ in the Middle East and North Africa region.

Poor life expectancy in Yemen of 54 years is attributed to inadequate health service and poor water and sanitation coverage. It is low when compared with the average of 67 years in the Middle East and North Africa region. Poverty in Yemen is high, with 191-26.92% of the households living below the poverty line (Ministry of Planning and Development, 1998; World Bank, 1999).

1.1.2 Water supply and sanitation

Coverage of the public water supply in 1990 was estimated to be 61% of the population in the urban areas and 47% in the rural areas. With exception of Aden and Dhamar, all cities rely on intermittent supply of water, where for example water is supplied to connected consumers every 2–4 days in Sana’a and every 1–2 weeks in Taiz. The cause of intermittent supply can be capacity problems in the infrastructure (Sana’a) or lack of water resources (Taiz). Overall access to safe water has been estimated to be 39%. With regard to sanitation, 10.6% of the national population has been estimated to have access to adequate sanitation services covering 40% and 1.2% of the urban and rural population, respectively. The higher access to sanitation services in the urban areas is due to the construction and installation of partial sewerage systems in the cities of Sana’a, Aden, Mukalla, Taiz, Hodeidah, Ibb, and Dhamar, collecting around 33 Mm3/a of sewage in 1990 (HWC, 1992a; Ministry of Planning and Development, 1998). The rest of the urban population relies mostly on on-site facilities (cesspits) for wastewater disposal. Unregulated on-site disposal of wastewater is of a major health and environmental concern, especially in urban, densely populated areas, placing the general public at risk from direct exposure to sewage in areas where the soil has reached its absorption capacity and sewage leaks onto the streets, and threatening to contaminate the groundwater aquifers used for domestic supplies.

Wastewater treatment plants (oxidation pond systems) have been constructed in Aden, Taiz, Hodeidah, and Dhamar. In Ibb however, an activated sludge plant was constructed in the mid 1980s. In Sana’a, the collected sewage is diverted to temporary overloaded oxidation ponds, which are to be shortly replaced by the newly constructed activated sludge plant. Effluent from the treatment plants of the various cities is mostly evaporating and leaching to the soil, with the remainder used for agriculture to irrigate mostly cereals and fodder crops. Given the extreme scarcity of water in Yemen, wastewater should not be wasted, but rather assessed and utilized in the overall context of water resources management.

1.1.3 Water resources

The total renewable water in Yemen is estimated at 2.1 Gm3/a, which translates into a share of only 130 m3/cap./a (World Bank, 1997). This is rather low when compared with the Middle East and North Africa average of 1,250 m3/cap./a and a world average of 7,500 m3/cap./a (Berkoff, 1994). With the relatively high population growth, the per capita share of renewable water in Yemen is expected to further decline to 90 and 72 m3/cap./a by the year 2010 and 2025, respectively. These figures reflect a very high level of water scarcity in Yemen, especially when compared with the stress level of 1,700 m3/cap./a considered as the minimum requirement for human needs (food production and domestic use) (Postel, 1992). As of 1994, the total water use in Yemen was estimated to have been around 2.8 Gm3/a, leading to a deficit of 0.7 Gm3/a. This deficit is mostly being overcome through the use of around 45,000 private wells withdrawing fossil groundwater, leading to groundwater mining and resulting in a decline of water levels in most aquifers. Agriculture is by far the largest water-using sector in Yemen, followed by the municipal and industrial sectors with shares of 93.1%, 4.6% and 2.3%, respectively. It is further estimated that 34%) of the total agricultural land (1,052,000 hectare) is being irrigated with groundwater (World Bank, 1997). Prior to the 1970s, Yemen was very secluded from the rest of the world, and nearly all agriculture was rain-fed. This, combined with low population pressure, in effect meant that the country’s water use was sustainable.

Within the northern, mountainous governorates, groundwater abstraction in 1990 was estimated at 1.5 Gm3/a, while the recharge to the same aquifers was estimated at around 1.0 Gm3/a, indicating that abstraction had exceeded recharge by around 50% (HWC, 1992b). Given the estimated usable storage of those aquifers (to a depth of 150 m) to be around 35 Gm3, and assuming a constant level of abstraction (which is an optimistic view), the total usable storage would be depleted within less than 70 years. Although groundwater mining is a common feature for the entire country, heavy mining is posing a serious problem in the northern high plain region, and particularly the Sana’a basin with an annual decline of 2–6 m in groundwater levels. Groundwater use has been accelerated during the last two decades due to the absence of any administrative or traditional control over drilling.

According to the classification proposed by UNESCO, the climate of Yemen varies from hyper-arid (in the deserts, most of the plateau, and parts of the coastal plains) to sub-humid (scattered wetter zones in the western and southern slopes) with a few humid spots on a very small scale. Despite shortages in extensive and reliable data, precipitation in general is considered to vary between 50 mm/a in the coastal plains to a range of 300–700 mm/a in the central and northern high plains. Average rainfall values higher than 250 mm/a are only observed in the western and southern parts of the mountain massive. Low rainfall is found particularly in Almaharah governorate and the northern part of Hadramawt governorate. Most regions of the country have two distinct rainfall patterns, with a first rainy season in spring (March-May) and a second during the summer (July-September) (Van der Gun and Ahmed, 1995). Rainfall usually comes in short intensive events or squalls. This often leads to temporary flooding that is evacuated via wadis. With the exception of small permanent springs in the few water-rich regions, e.g., Ibb, the country does not have perennial rivers.

The introduction of drilling rigs and powerful pumps in the late 1960s has enabled the abstraction of large quantities of groundwater from deep boreholes. Farmers have been active in groundwater development during the last two decades. Water allocation generally follows the traditional principles of the Islamic system. Traditional spate irrigation is governed by the principle of Ala’ala-fa-ala’ala, giving upstream land senior irrigation rights over downstream land. With regard to groundwater, the Islamic principles treat it as a communal property with a possibility of private ownership under special circumstances (Chapter 4) (Caponera, 1973; Al-Eryani, 1995). This system addresses the issues of equitable and productive access to groundwater, but fails to provide a regulatory framework to ensure sustainability. Hence, regulating heavy competition for and abstraction of groundwater has become a burning issue.

Before the establishment of the National Water Resources Authority (NWRA) in 1995, no governmental agency was responsible for overall water resources management. Other than NWRA, currently two ministries are involved in water services, namely the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MAI) and the Ministry of Electricity and Water (MEW). The latter incorporates two general authorities, namely the National Water and Sanitation Authority (NWSA) and the General Authority for Rural Electricity and Water (GAREW). While the responsibility of MAI is clearly directed to irrigation projects, NWSA is responsible for both domestic water supply and sewerage services in the urban communities, while the GAREW is mainly responsible for water supply in the rural areas.

1.2 The Sana’a Basin

1.2.1 General overview

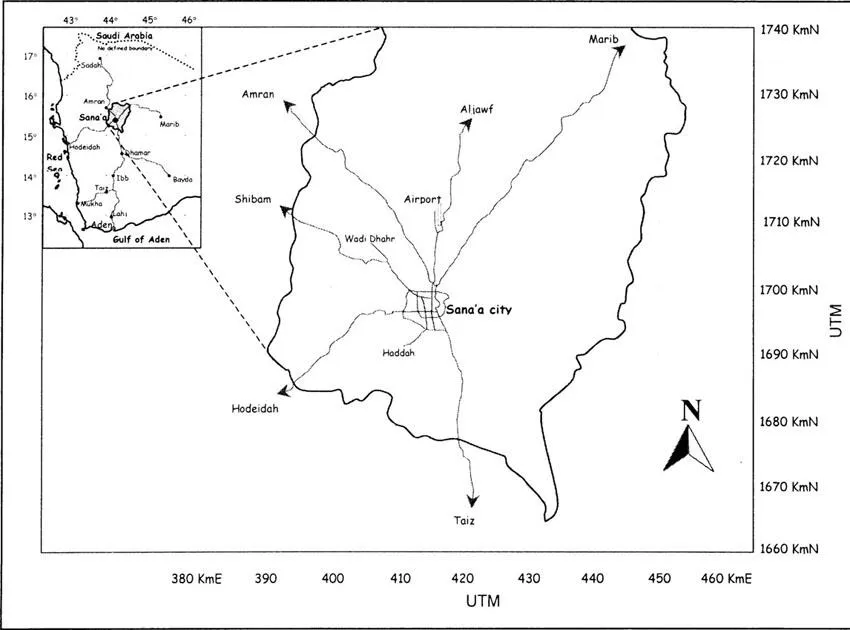

The Sana’a basin is located in the central highland of Yemen covering an area of around 3,200 km2 (Figure 1.1). The basin area varies in elevation between 2,200 meter above sea level (masl) in the Sana’a plain to more than 3,000 masl in the surrounding western, eastern and southern mountains. The basin is sloping mildly downward in a south-north direction. The climate of the basin is classified as semi-arid with an annual average rainfall of 230 mm at Sana’a city. The basin area contains parts or all of eleven administrative districts of the Sana’a governorate, in addition to the capital city of Sana’a (the main urban area within the basin). The population of the basin area in 1995 was estimated to be 2.0 million, of which 972,000 (48%) live in the city and the remaining 1.03 million (52%) live in rural areas. It is projected that the population of the basin will increase to 3.4 million and 6.06 million by the year 2010 and 2025, respectively (HWC, 1992c; Foppen, 1996; World Bank, 1997).

Land use within the basin falls into four categories: (1) agricultural land (33.2%), (2) urban and built-up land (3.8%), (3) range land (27.2%), and (4) unusable land (rock outcrops) (35.8%). Agricultural land is further subdivided into rain-fed areas covering around 67%, and groundwater irrigated areas covering the remaining 33%. Under groundwater irrigated land, qat3 is estimated to cover around one third of the total area, followed by grapes and vegetables with 25% each (Bamatraf, 1995).

The heavy reliance on groundwater has resulted in groundwater mining leading to a substantial drop in water levels (2–6 m/a)4. Estimates of the natural recharge to the basin vary between 28–60 Mm3/a, with 42 Mm3/a as the latest estimate. Much of the recharge is derived from the intermittent runoff along the wadi courses discharging to the Sana’a plain. Direct recharge from rainfall is limited due to: (1) low rainfall, (2) high soil moisture deficit, and (3) thick unsaturated zone (Italconsult, 1973; Howard Humphreys, 1977; Charalambous, 1982; Mosgiprovodkhoz, 1986; Foppen, 1996). In addition to the natural recharge, there are two other recharge mechanisms currently taking place within the basin area, namely infiltration of domestic sewage (13–15 Mm3/a) (Chapter 2) in Sana’a city and return flows from irrigation (roughly estimated to be 20–25% of total irrigation water application) in the rural areas. The commendable groundwater storage of the basin to a depth of 250 meters below ground level (mbgl) is estimated at 6,050 Mm3, of which around 50% (3,220 Mm3) is considered usable storage (HWC, 1992c).

Although the Sana’a basin is not confined to a single distinctive administrative setup, it is entirely confined to the Sana’a governorate. Furthermore, the basin area comprises entirely or partially eleven administrative districts5 of the Sana’a governorate (Foppen, 1996). Like in all parts of the country, the tribal structure divides the rural areas of the basin into small tribal regions (villages or settlements) grouped at the highest level into the two major tribes of Yemen (Bakeil and Hashed). It is quite normal to find two neighboring villages belonging to the different tribes. It is usually found that a village (in its entirety) belongs to only one tribe; however, field observations in the village of Sarif shows that due to a long and bloody conflict between its members, this particular village was finally divided into two parts, with each part belonging to a different tribe.

1.2.2 Water availability and demand

1.2.2.1 General

Within the Sana’a basin area all water needs are being satisfied from groundwater...