![]()

CHAPTER ONE

There’s a strong argument for the two most influential punk bands of all time being the Sex Pistols and CRASS; the former encouraged bored teenagers everywhere to get off their arses and start their own bands, the latter encouraged them to think for themselves. Of the two bands, however, the shadow cast by Crass is certainly the one with the most substance; they gave the ephemeral rebellion hinted at by the Pistols specific shape and purpose, and a thousand anarcho-punk bands set sail in their wake. And these bands weren’t thrashing against any imaginary opponent conjured by the paranoia of youth… no, they set themselves very real targets and clearly defined – if a little ambitious – objectives. They weren’t interested in sensationalist, unworkable notions of anarchy and chaos, they wanted a gradual revolution from within; they wanted anarchy, peace and freedom. The shock tactics of punk had been usurped, given an articulate intellectual make-over, and were now being put to sound social use.

“Well, I don’t think that we were leaders of any movement,” says drummer Penny Rimbaud (real name Jerry Ratter) modestly, “although we may have helped inspire one. And we ourselves were inspired by some of the earliest punk bands, but what we aspired to do was what they only pretended to do. Commercial punk was a complete sham, part of the whole rock‘n’roll circus, operating in the same way as someone like Marc Bolan – which is not to denigrate it as such… after all, music is an industry; it produces product and people enjoy product. But to imagine that the first wave of punk related in any real way to what followed is quite inaccurate, and it was basically finished by late ’77.

“And that particular element of rock‘n’roll that was called ‘punk’ would have died a natural death, and the next phase, be it goth or whatever, would have been invented by the music business. It would’ve required its main characters, of course, but would have just continued along the same line that rock‘n’roll has always continued along for many, many years.

“We sort of tail-ended that first wave,” he adds, of Crass themselves. “We were playing through ’77, playing a lot with bands like the [UK] Subs, for example, and being talked about in the same breath. We didn’t see any great disconnection really, but we actually wanted to put into action what had never been the intention of those earliest punk bands. We picked up their pretensions and tried to make them real. We came in with their energy, but also a great deal of political sincerity, and it was the political sincerity that attracted and created a movement. You could never have created a ‘movement’ out of something as banal as punk rock.

“I mean, they were playing a Clash record on the radio earlier on today, and it struck me that you couldn’t really tell the difference between that now and the Rolling Stones. It was just rock‘n’roll at the end of the day, just music.

“It was our sincerity, and our authenticity, that made us different. Of course, it’s only now that I’m aware of the authenticity part, but I was certainly aware of the sincerity even then; we genuinely meant that anyone could get up and do it. Because we had gotten up ourselves and done it! Most of the bands before us had been pub bands, on some sort of circuit; they’d already tried some form of rock‘n’roll, just commercial players looking for a break… but we were saying, ‘Have a go!’ And we really meant it. And when we set up our own label, at least initially, anyone who said they wanted to get up and play could get up and play. And we ourselves were happy to play with anyone else; we couldn’t see that what we were doing was any different to what the Subs were doing, but it soon became clear that we did mean it. And we were quite prepared to put what little money we made – actually it was quite a large amount of money – back into promoting those ideas.

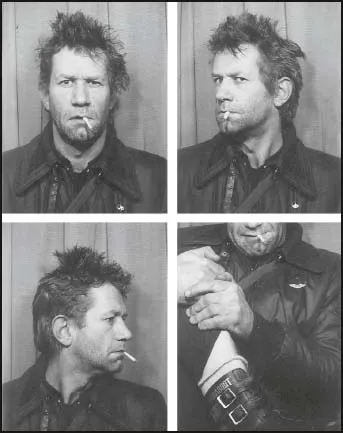

Penny Rimbaud (AKA Jeremy Ratter), drummer and co-founder of Crass.

“If what you’re saying is that we created the anarcho-punk movement, then we didn’t create it as leaders. We were just as hard-working as anyone else, scrubbing floors, knocking out leaflets, carrying our own gear – and everyone else’s too! We never separated ourselves; we were a part of it, at one with it. There were those that tried to force that sense of leadership onto us, but I think we were very successful in never, ever accepting that role.”

Crass were never your ‘typical band’ from the off. The truly unique chemistry that set up the claustrophobic tension so inherent in their sound was a result of many factors, including disparate musical tastes, but more importantly differences in age and class. Penny was a 35-year-old ex-art teacher, living a communal life at Dial House, on the edge of Epping Forest, whilst vocalist Steve (‘Ignorant’) Williams (who’s actually anything but) was a fifteen-year-old yobbo from Dagenham.

“It all came about through my older brother, who would turn up at people’s places, ask to stay the night and then end up staying three weeks,” laughs Steve, by way of explanation of how he and Penny hooked up. “He’d stayed at Dial House for two nights or something, through some hippy types that he knew down in Ongar, and he came over to see me where I lived in Dagenham – this is pre-Crass, by the way, when I was only about thirteen – and he told me about this amazing place where you could go and draw if you wanted to, go and play piano if you wanted to, whatever… and he took me over there. I was totally intrigued by it; I was an ex-skinhead, and I turned up in all this gear, really loud ‘Rupert The Bear trousers’, checked jacket… and there’s all these people walking around bare-foot, with no fucking television! Talking in these accents I couldn’t understand, using all these words I couldn’t comprehend, and sounding like they had fifteen plums in their mouths!

“But also, for the first time in my life, I was actually being included in the conversation… even though I didn’t understand what they were going on about; they treated me like an equal, y’know? If I said something, they would consider it… it was the first time that I thought, ‘Well, yeah, I have got something to say.’

“So, I kept playing truant, and going back there to stay, but then I left school and moved to Bristol for about a year, and then punk came along. I went to see The Clash at the Colston Hall, which totally did it for me, and Joe Strummer said, ‘If you think you can do better, start your own band…’, which became my battle cry. I came back to Dagenham – the week of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, I think it was – with the idea of finding my old drinking buddies and starting a punk rock band of my own. But of course, none of them were having any of it, ’cos they all had wives and jobs and all that bollocks, so I came out to Dial House, to find that Pen was living there on his own, writing ‘Christ, Reality Asylum’. Gee [Vaucher, who would become the band’s graphic designer] had gone to America, doing illustration work, and so he said, ‘What you up to?’ And I said, ‘I’m gonna start a band…’ to which he replied, ‘I’ll play drums for ya!’ And that’s how it all started really. His previous band, Exit, had stopped performing properly in ’74, but people would still come over at weekends and jam… and what a fucking racket that was!

“Anyway, I turned up wanting to be Johnny Rotten or Paul Simonon… ’cos he was a good looking bloke, always looked a bit tasty… and with my David Bowie background, sort of thing, a part of me always wanted to be famous. And then you had Pen’s background, which was much more intellectual, and it just came together. I couldn’t even understand what ‘Christ, Reality Asylum’ was all about, but I knew I liked it because it was having a pop at religion, and it had ‘fuck’ in it, which was well punk rock, wasn’t it? I dunno, we just got on really.

“Dial House was this place where everyone could go; there was this idea that if you were a poet and you turned up, you could earn your night’s board by reciting your poetry, for example, and there was going to be all these Dial Houses all around the country. So you had all these people turning up who weren’t working class – they tended to be middle class and into photography or film-making – and Pen used to like them turning up and being confronted by me, this spiky-haired, spotty little oik, ’cos punk rockers were still ‘frightening’ back then. And I used to enjoy seeing that happen as well, my so-called ‘elders and betters’ being a bit scared of me, so that worked for us as well; it was a little bit of a stage act, a performance. The funny thing was, as soon as Crass started, a lot of the people who used to visit Dial House stopped coming anyway – ’cos the whole place would be full of Italian punks or whatever!

“So yeah, there was a class difference – I remember I always felt really nervous in front of Pen’s mum and dad – but it worked for us; it was a good mixture, and I don’t really know of any other bands that had that…”

That early poem of Penny’s, ‘Christ, Reality Asylum’, remains a tenet of the Crass canon, an outrageously focused cornerstone from whence the band developed and refined its gleefully confrontational style and approach. With its condemnation of Christ’s martyrdom as a ‘churlish suicide’, exclaiming that Jesus hung ‘in crucified delight, nailed to the extent of his vision’, it was deliciously, shockingly blasphemous, and was always destined to land the band in trouble with those kind-hearted censors that safeguard our precious morality. When the band’s first 12” came out, the song was left off by the outraged pressing plant that manufactured it, forcing the band to name the silence left in its place ‘The Sound Of Free Speech’.

“But there were no ‘tactics’ as such,” claims Penny. “I had this friend staying with me, the guy who actually designed the Crass symbol, a bloke called Dave King who now lives in San Francisco [and was later a part of the Sleeping Dogs, who released their 1982 ‘Beware…’ single through Crass]. And we were both from upper-middle-class backgrounds, and we were talking about religion, and I went off on this rant, and I ended up rolling around on the floor, doing all these theatrics. And he said, ‘Fuckin’ hell, you ought to write that down!’

“I was so in the moment, tearing up all this stupid religious tradition, and I realized that I was 35 years old but still bound up with this superstitious rubbish, and it all started falling away when I started getting into the rant. So I got up off the floor and wrote it down, carried on ranting but onto paper, and that became the ‘Reality Asylum’ book, and the ‘Crass logo’ was actually a symbol that Dave designed for the frontispiece of the book. But no, there was no intent there; it was just what I was feeling at the time…”

With Penny on drums and Steve providing vocals, the duo began writing their own material, Steve’s searingly blunt approach providing the perfect foil for Penny’s more considered, cerebral musings. The contrast between their very differing approaches can best be gauged when comparing ‘Reality Asylum’ to Steve’s first composition, ‘So What’.

“Well, actually, the first song I ever wrote was probably something like ‘Song For Tony Blackburn’, which only ever appeared on a tape or whatever,” corrects Steve, “And the first proper song I wrote was ‘Do They Owe Us A Living?’ The second one was ‘So What’, I think, and by then I’d sat down and read ‘Reality Asylum’. To be honest, it really annoyed me in a way; it was all ‘I’, ‘I’, ‘I’, ‘you’, ‘you’, ‘you’, ‘me’, ‘me’, ‘me’…

“Then again, when I look at how we laid the lyrics out on [that first 12”] ‘The Feeding Of The 5000’, with all the obliques and no punctuation, I find that annoying as well, but at the time, I agreed with the others that if we made it difficult for people to read, they’d have to concentrate a lot harder.

“Anyway, little did I know that the first song I ever wrote, ‘Owe Us A Living’, which I sang under my breath, marching back from the shops going, you know, ‘Fuck the politically minded…’, would be the main song that I’m remembered for. And all the other songs I’ve written that I consider far better than that – ’cos I’ve written some great songs since Crass – no one knows, or cares, what they fucking are! And if I formed another band tomorrow, you know full well that there’d still be people shouting for ‘Owe Us A Living’ even now…

“To be honest with you, we never thought it would get any further than the music room at Dial anyway; it would just be our little hobby… we never dreamt we’d ever get a gig. We didn’t take ourselves that seriously, to start with. Then this guy turned up called Steve Herman – he was a bald, beardy bloke with glasses and sandals… didn’t look anything like a punk, but he could play guitar, and we thought, ‘Fuck it, it’s punk, anything goes!’

“And then Andy Palmer turned up; he couldn’t play and he didn’t have a guitar, but he nicked one from somewhere and tuned it so he could play a chord by putting his finger straight across. And then [bassist] Pete Wright became involved… but even then, it was like a weekend thing – it was only once we’d done a couple of gigs, that we thought we were maybe onto something. And we were still going on blind drunk at that point, just having a laugh really.”

“Yes, it was Steve and myself at first,” clarifies Penny, “And Eve [Libertine, real name Bronwen Jones, one of their vocalists] used to live just up the road, a mile or so away. She used to come down, and although she didn’t join in with the band for the first year, she was quite instrumental in the nature of how we grew – especially the feminist aspect of it all. It was Eve that disallowed our use of the word ‘cunt’ in the lyrics.

“And because we’ve always been this cultural centre [at Dial House], we’ve always had people coming and going; there’s always been an itinerant body of people moving in and out – some of them stuck and some of them didn’t. We never ever thought to ourselves, ‘Oh, we need to get a bassist’, or anything. People just turned up.

“I remember Andy turning up; he was at a local art school, and he’d never played an instrument in his life, but he nicked one from the International Times offices, and came round and said he wanted to be in the band, so he was. That’s how it worked; we were just mucking about. Me and Steve originally called ourselves ‘Stormtrooper’… Eve thoroughly objected to that, and thankfully persuaded us otherwise!

“But really it all just happened, it wasn’t by design. Although there did come a point after the first year, when we realised that we were basically fucking ourselves up, drinking quite a lot and using other substances. We couldn’t have kept going like that, so we had to say, ‘Are we going to take this seriously, or are we just going to carry on pointlessly like this?’ So we had this big conference for a whole day, which was very self-conscious, and we made these decisions about what we were going to do, and those things stuck. And by then, all the different people who were going to be in the band were already in the band, and from then on we only incorporated extra people if they could actually add something to it. So we had filmmakers and poets turn up and get involved, and I suppose if a saxophonist had turned up, we might have got them in as well, but they didn’t!”

Prior to them sobering up though, the very first Crass gig was during the summer of 1977, somewhere on the Tottenham Court Road… although the band didn’t actually get to perform their full set.

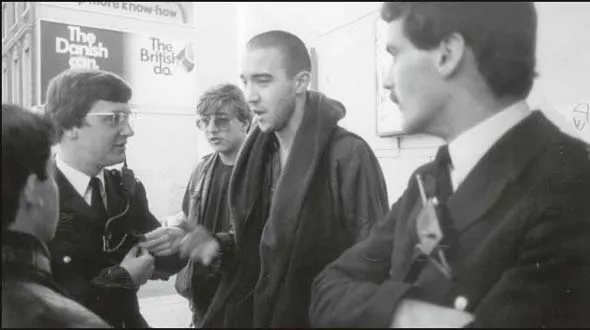

Andy of Crass debating with police outside the Zig Zag, picture by Tony Mottram.

“There was a big squat there back then, with a big yard out back,” recalls Penny, “and we did three-and-a-half songs, before we got switched off by this retired colonel, who thoroughly objected to what we were saying! It was a very nice squat, very regula...