![]()

PART I SIR ROBERT

![]()

Okay, BITCH! I got another one of your FUCKIN’ numbers! I’ve already got seven! No, this ain’t the number, call the other number! You call the other fuckin’ number and you gotta wait for another fuckin’ number! Then call fuckin’ Baltimore! Then find out what state you’re in. Then call THAT fuckin’ number! And then find out they didn’t take the fuckin’ Medicare!”

My mom was on the phone again.

“Now, cunt Mary motherfuckers of the planet, YOU do this shit! All this shit! Every fuckin’ time for TWENTY YEARS I have called these motherfuckers it’s like this! Don’t know what the fuck you’re talkin’ about!”

I was around fifteen years old, just getting into hip-hop and recording everything I could all the time, songs off the radio, stuff off the TV, my friends goofing around. So one day I decided to record one of her phone calls.

“Fuck it! I’m a psychopathic, cocksuckin’ fuckin’ sinner! Jesus, if you’re going to do something to me, then DO IT! I can’t fuckin’ take it!”

What you can’t hear on the page is that she’s screeching so loud the neighbors can hear it in the next apartment, and what you can’t see is that she’s frantically pacing back and forth, chain-smoking, slamming her fists on the kitchen counter, and throwing shit at the wall, like a child having a tantrum because she’s been put on hold for the millionth time.

“Yeah, you stupid cunt, it’s correct! Fuckin’ bastards! Fuckin’ swine! Fuckin’ motherfucker! Are you gonna fuck with me or help me?!”

It was like this every day, and this was mild.

“Fuckin’ bitch! Fuckin’ knows how to fuckin’ tell me how to fuckin’ CALM DOWN! She can’t even fuckin’ see the name of the fuckin’ benefits!”

She was calling some government agency about her medication, whichever pill she was taking that month to balance her brain. Zoloft, maybe. I can’t remember them all. One day it was her medication, the next day it was welfare or food stamps.

“All I want to know is if these GODDAMN people pay for this FUCKIN’ medicine! Because what am I supposed to fuckin’ do?! Go back to the fuckin’ doctor here? This medicine they don’t pay for. I don’t know… write me out another one! Okay, here, go to the pharmacy. Oh, they don’t pay for this. Okay, let me go back to the doctor again! Here, hmmm, let’s see… take this medicine!”

She was a sick person, and she was in pain, so she was lashing out at the people who were trying to help her. Which is pretty much the story of her life.

“Thanks! That’s all the FUCK I wanted to know! Why couldn’t I get somebody a fuckin’ half hour ago to say that! We’re dropping like flies ’cause we fuckin’ want to kill ourselves so they get a POPULATION CONTROL!”

Whenever I tell my story and I get to the stuff about my mom, part of me feels like a liar and a fraud, like I must be exaggerating this stuff to make myself sound tougher, because if I tell it this way, I’ve got one of the craziest American come-up stories in history. Then I go back and listen to this tape, and I remember: “Oh. Right. It was actually more fucked up than what I usually tell people.”

Still, as strange and fucked up as my life may have been because of her, her life was actually way worse than mine.

![]()

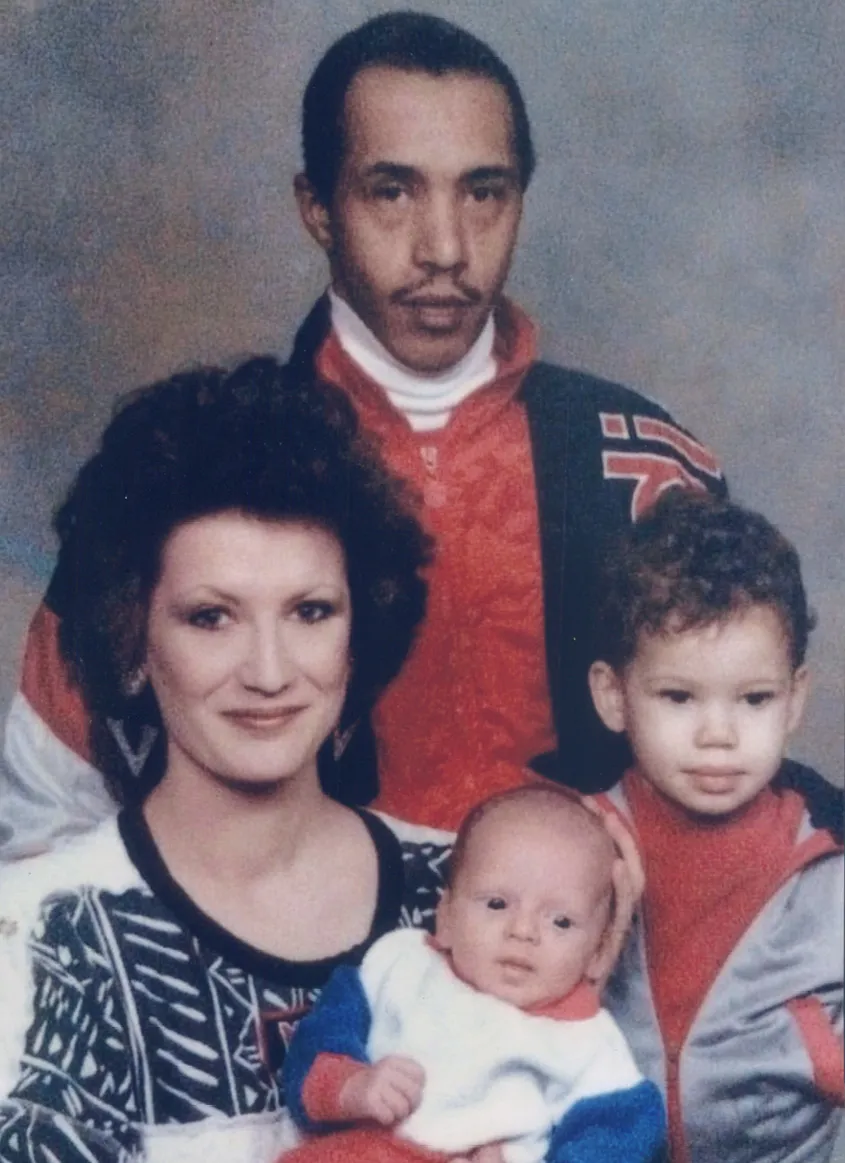

My mom was born in 1961 in Washington, D.C. Back then, before all the husbands, before she was Terry Lee Bell or Terry Lee Stone or Terry Lee Bransford, she was Terry Lee Miller. But all the rotating last names didn’t matter so much because my whole life everyone just called her Terry Lee.

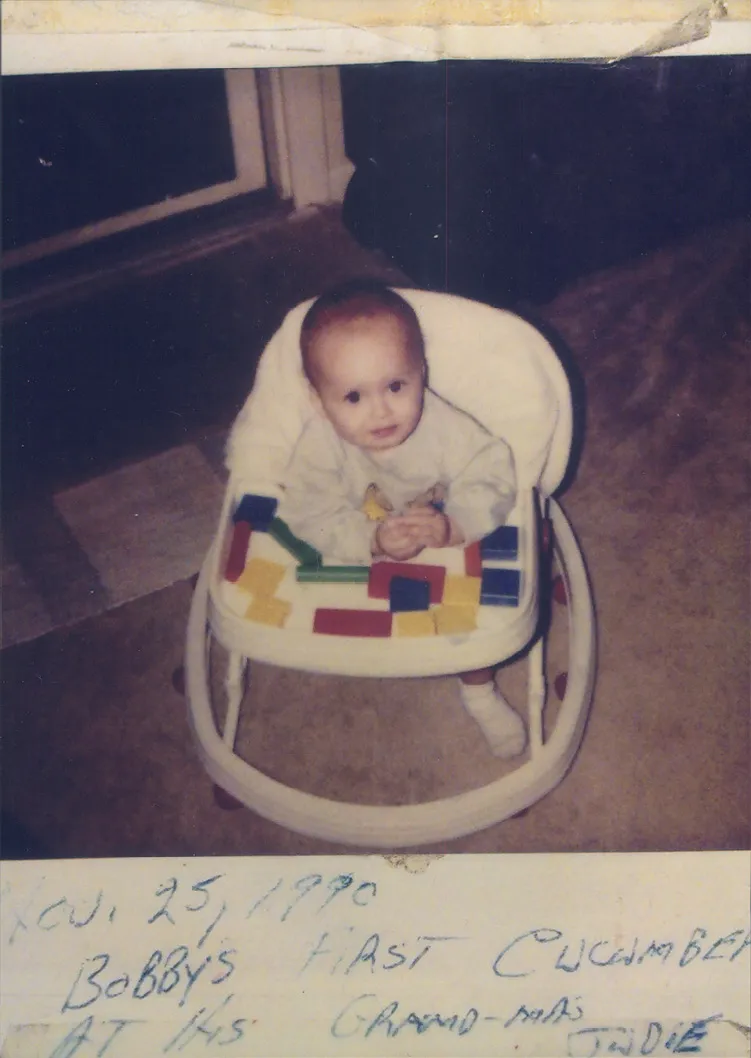

By the time I was born, my mother was estranged from her family, so I don’t know a whole lot about them. From what I understand, they were well-off. Not super-wealthy or anything, but they owned a house and a car and things like that. My grandfather, I don’t have any memories of him at all, not even what his name was. I know my grandmother’s name, but only because I found it once on the back of an old photograph. I don’t have many pictures of me as a child, a dozen maybe, but there’s this one Polaroid of me as a ten-month-old baby, and on the bottom it says, “Nov. 27, 1990 Bobby’s first cucumber at his Grand-mas Judie.”

So that was her name: Judie.

My mom told me her heritage was German and English, which to look at her was true, I guess. She had green eyes and pale skin with freckles and brown hair that she always wore short, never past her shoulders. I never saw my mom as ugly, but I wouldn’t say she was particularly attractive. Her teeth were all crooked and filled with gaps and she was insecure about them. We’d be watching Seinfeld in the apartment, and whenever she laughed she’d cover her mouth, even with nobody else there.

I only know two stories about my mom growing up. The first one she always used to tell was how when she was five she got this brand-new Schwinn bicycle, the one with the banana seat. She loved it so much and she used to ride around her neighborhood and it was on one of those rides that she was sexually assaulted for the first time. A man in the neighborhood exposed himself to her and made her touch his penis. She went and told her mom, but her mom reacted like too many people do when it comes to sexual abuse. She tried to minimize it, bury it. She told my mom that the man was just playing a game and not to worry and let’s all get back to pretending everything is normal and perfect. Which fucked my mom up, obviously, as it would.

The other story my mom told me was how when she was fourteen she brought home a boy she wanted to date. His name was Duncan, and he was black. “Duncan was so beautiful and sweet and kind,” she used to say, but then her parents completely flipped out on her. “We don’t mix with those people,” they said, and they made her break up with him. Something about that incident had a huge impact on her, though I’m not entirely sure why. For the rest of her life, she was attracted to black men. She had all of her children with black men, and I only ever saw her with one man who wasn’t black, her second husband, Kenny. At the same time, deep down, because of her upbringing, part of her was every bit as racist as her parents.

The Duncan story and the bicycle penis-touching story are the only ones I know. She never told me anything else; it was like she didn’t have a childhood. Everything else I know about her starts when she was seventeen, when she ran away from home and fell into drugs and prostitution. I don’t know if she ran away because her parents were abusive or if that’s when her issues with mental illness started to come up. All I know is that my mom never fit in, with her family, or with anyone, anywhere.

The impression I have is that when she ran away she was a stoner pothead, hanging out with the white guys listening to AC/DC and the brothers listening to Run-DMC. I imagine her life being like that movie Detroit Rock City, a bunch of burnouts having a good time trying to scam their way into a KISS concert. But things turned dark pretty fast.

She never talked much about her prostitution years. The subject would only come up every now and then, typically out of anger, as a weapon she could wield against me. I’d be watching cartoons and bouncing off the walls, being a typical kid, and she’d flip the fuck out and start screaming at me, and I’d be like, “But Mom. I’m just having fun.”

“Fun?” she’d scream. “You want to have fun?! You should just be grateful that you have a fuckin’ place to sleep and live and eat, because I sure fuckin’ didn’t. You don’t even fuckin’ know. When I was a kid, I didn’t have anywhere to go. I had to walk the fuckin’ streets at three a.m. getting picked up by truckers who raped me and threw me out and left me for dead on the highway!”

In another story she told me, she was in an apartment with these two guys and one of them put a butcher knife on the stove until it was red-hot and then he held her down and sodomized her and said if she made a noise he’d stab her with it.

“He sodomized me,” she said, red-faced and screaming, as usual. “That means he stuck his dick in my ass.”

She told me that when I was maybe about ten.

Then there was the one she told me about why she was mostly deaf in her left ear. It was permanently damaged from when some man had been beating on her.

Once she started in with these stories, she’d get so wrapped up in her own pain that she’d start lashing out, like she did with the people on the phone. Since I was the only person there, she’d be lashing out at me. “You don’t know what this world is,” and “You’re gonna feel real pain one day,” and “I hope you feel pain!” and “You deserve to feel pain!” She’d be screaming this shit at me, and I’d be thinking to myself, “Bitch, I’m just trying to watch SpongeBob.”

At some point in those years my mom married her first husband, Eugene Bell, a guy she met at a party. Eugene played guitar and buckets on the street. Black guy. Dark skin. They had three kids together before getting divorced. There’s Amber, who’s the oldest, seven years older than me; then Geanie, who’s five years older; and then my brother Jesse, who’s only two years older than me. When Jesse was five, Eugene took him and climbed up a tree with him so he could videotape a woman undressing in her apartment. He did this with his kid—that’s the kind of guy Eugene was.

Even though he got caught doing that shit, he still had primary custody. Which is crazy, but it probably says a lot about my mom. So my siblings sort of lived with us sometimes, but mostly they didn’t. I have no memories of us sharing a home and being a family. The only real memory I have is them throwing me a birthday party when I turned four. It was weird because I didn’t know what a birthday was, since no one had never celebrated my birthday before. I woke up and walked out to the living room and in this beautiful morning light there were balloons everywhere and cut-up pieces of construction paper all over the floor like confetti. I went and woke up my brother and sisters and said, “I don’t know what’s going on. I think a clown broke into the house or something.”

“Dude,” they said, “it’s your birthday!”

“My what?”

“Your birthday!”

And that was the last time I saw them. Not too long after that Eugene threw them on a Greyhound bus and took them to California and by my fifth birthday they were gone, which I know for a fact because now that I knew what a birthday was I woke up and ran out of my bedroom yelling, “It’s my birthday, Mom!” But I didn’t get shit. No balloons, no cake. Nothing.

From then on, it was like I was an only child. We never had any family besides me and my mom. What’s crazy is that I felt that way even though my mom’s parents still lived a few miles away. I’ve got the picture of me eating cucumbers at Judie’s house, so I have to assume my mom and her parents tried to reestablish their relationship, but it didn’t work out. The only real memory I have of my grandmother is calling her and asking if I could come spend the weekend, and her giving me a bunch of excuses why I couldn’t.

“Can I come and stay with you?”

“I don’t think we can right now.”

“What about the guest room?”

“Well, it’s being worked on.”

“What about the couch?”

“Oh, you don’t want to sleep on the couch.”

“What about the floor? I’ll sleep on the floor.”

I kept trying, and she kept saying no. Part of me, thinking back to the story about Duncan and why my mom ran away, wants to believe that the rift between my mom and her family was because I was black, because they were racist. And that had to have been part of it; racism never makes anything any easier. But ultimately I think the reason my mother’s family wasn’t in our life was because of my mother. Some people are so toxic you have no choice but to cut them off, and my mom was that person. Because of the cucumber photo, I have to believe that my grandparents at least tried to help me and eventually gave up because they were like, “We can’t fuck with this bitch. She’s crazy.” Which is why it was always just me and Terry Lee, and everything I know about her family and her life is from her screaming at me during SpongeBob.

But as fucked up as my mom’s stories are, I absolutely believe that they’re true. You’d think that someone like her wouldn’t be the most reliable narrator of her own life, that her stories must be delusional or detached from reality. But whenever she talked, she talked like someone who’d been scarred, who’d relived those stories a million times in her head. The details were always the same, too, like they were burned into her memory. That shit’s real, for sure.

Then there’s my dad.

![]()

The hard thing about my dad’s story is that it’s impossible to know what’s true and what’s not because he’s a fuckin’ liar. All I can do is piece together the half-true stories he’s already told me because he isn’t in my life right now. Maybe he will be again someday, but recently I had to stop talking to him because he asked me for eight hundred grand so he could buy a house and turn it into a studio for his band.

We’re working on boundaries.

Robert Bryson Hall was born somewhere in Pennsylvania. That much I know is true. I also know he had two brothers. His brother Michael was a cool dude; I got to meet him and know him a bit. There was another brother, too, but I forget his name. He died. It might have been drugs. I have an aunt on that side, too. She sent me a letter a couple of years ago, but I’ve never spoken to her. I think her name is Robin or Roberta or something like that.

Both of my dad’s parents were alcoholics. I never met them because they both died long before I was born. My grandfather, as the story goes, went out on Christmas Eve and got shitfaced drunk and as he was coming up the front steps he slipped on the ice, fell back, hit his head on a rock, knocked himself out, and froze to death in the snow. They found him on Christmas morning. Crazy.

My grandmother had a serious drinking problem, too. What my dad told me about her was that she drank herself into some insane state and had to go to the hospital and practically went into a coma. When she came to the doctors told her, “If you drink again, you’ll die.” Not long after that, she was at a Christmas party—which is weird, because of how her husband went—and she got drunk and fell asleep in a chair and never woke up.

My dad has told me those stories a few times and the details always add up and there’s no reason why my dad would lie about how his parents died, but I still can’t be sure since he’s told me so many stories where the details don’t add up at all. For most of my life, pretty much everything that came out of my dad’s mouth was bullshit. He’s a slick motherfucker, for sure, the definition of a hustler—a smooth, silver-tongued dude who can talk his way into or out of just about anything. With the exception of fatherhood. He denied that I was his when I was born, but then he got a paternity test, which I had no idea about until a couple of years ago when my dad, who’s now a recovering crack addict in his sixties, found out that he’d knocked up a twenty-three-year-old heroin addict even though he got a vasectomy after he’d had me.

“Can you believe this shit?” he said. “I got a vasectomy and I’m still having another kid.”

“What the fuck?” I said. “When did you get a vasectomy?”

“After I had your ass.”

“Damn. Well, how do you know it’s yours?”

“Because I got a paternity test.”

That gave me this feeling I couldn’t shake, so a couple of months later I called my dad and said, “So, wait… did you get a paternity test with me?”

“Fuck yeah!” he said. “You know I did!”

So that was special. I don’t know if the test was something my parents did together, but the safer bet is that the motherfucker snuck me off somewhere and got a paternity test on his own—you know, just to be sure—and it came back positive. But he didn’t need a test to tell him that. He’s 100 percent my dad. We’re both skinny and lanky, both with the same hunched-over posture that we need to work on. The only difference is that while I look mixed, he’s definitely a black guy.

At some point my dad moved to D.C. with huge ambitions as a musician. He played congas and percussion and sang all over the Chocolate City Go-Go scene. He played with Chuck Brown. He played in E.U. What he wanted more than anything was to be Smokey Robinson. He’d introduce himself that way, too. “Hi, my name’s Smokey.” So everyone called him Smokey, which I find hilarious ’cause he’s a crackhead who named himself Smokey. And when it wasn’t Smokey Robinson, it was Prince. I think I heard my dad cover “Purple Rain” about a million times.

My dad was a legit musician, though. He had real talent. But he was also an addict. My whole life I’ve met people who did gigs with him, and they’ve all got stories. After the show, he’d go to the promoter and get the money and then run out on his bandmates. Like, he’d do that to his own people. Did he think he was never going to see them again? But that’s an addict’s mentality. He cou...