![]()

1

Integral Theory and the Principles of Integral Psychotherapy

Integral Theory is primarily the creation of philosopher and theoretician Ken Wilber, who is one of the world's most widely read and translated living philosophers. Integral Theory is essentially a synthetic philosophy, and Wilber's greatest ability and contribution has been to weave together a wide array of seemingly disparate schools of thought (S. McIntosh, 2007). He has accomplished this in the realm of psychotherapy, offering a synthesis between different schools of psychotherapy, as well as between the therapeutic field as a whole and the esoteric, meditative traditions (see Wilber, 1973, 2000; Wilber, Engler, & Brown, 1986). However, the “how to” of putting Wilber's ideas about psychotherapy into practice has not always been clear to therapists, despite a great deal of appreciation for his insights. Because Wilber himself is not a clinician, it seems natural that the task of describing how these ideas apply to real clients in real therapeutic situations falls upon those of us who are. This chapter begins that process.

This discussion begins with some framing comments about the Integral system and its basic intent. We will then move to describe the five basic features of the model—quadrants, stages, lines, states, and types—staying close to practical considerations and leaving aside unnecessary theoretical complexities.1 These five facets of the theory, which are addressed in greater depth in later chapters, will inform the five basic principles of Integral Psychotherapy. The chapter concludes by defining the major approaches to psychotherapy that the Integral approach attempts to synthesize. It should be said that this chapter, by necessity, is the most general of the text; the chapters that follow contain more nuances, suggestions, and ideas directly relevant to psychotherapy. The encouragement is for readers to stick with this chapter—even those who might be already familiar with Integral Theory—as the ideas set forth here create a foundation for the rest of the text.

The Overall Purpose of the Integral Approach

The major purpose of the Integral model—if one is trying to be concise—is to learn to use the insights of the various fields of human knowledge in a complementary way. Integral Theory attempts to bring together the most possible numbers of points of view on an issue, with the intention of creating more multifaceted and effective solutions to individual and social problems.

Why don't people already do this? Why does one even need an integrative approach? One way to answer this question is to point out the modern problem of overspecialization, or the tendency of different theorists and research traditions to stay confined within a very narrow niche or perspective, while tending to ignore what others are doing. Overspecialization manifests itself in many ways in our field and beyond. In psychotherapy, one negative consequence has been the proliferation in the number of available therapeutic modalities—some estimates are as high as 400 different systems (Garfield & Bergin, 1994; Karasu, 1986). Often, people who create new approaches try very hard to distinguish what they are doing from pre-existing approaches without attempting to incorporate or account for the value of what has come before.

The Integral approach would suggest that these problems of hyperdifferentiation and theoretical discord can be seen as the symptoms of a larger philosophical problem, whether they arise in psychotherapy or in other practical or academic disciplines. And that problem comes down to how we have tended to answer some very basic questions, including “What is real?” and “What can we really understand about ourselves and the universe, and how can we acquire this knowledge?”

People throughout history have answered these questions in a number of fundamentally different ways. Furthermore, they often hold unquestioned assumptions about their particular answers that can be used to deny or negate other views. If, for example, a biologist sees human biology as the “real” thing and human thought and emotion simply an extension of that, he or she has less incentive to see psychology as being equal in value to the facts of biology or neurology. Similarly, a psychologist may ignore or downplay issues of politics and economics because they are secondary (depending on his or her specific orientation), to the impact of childhood experience with the primary caregiver. There are many possible ways in which a person's main orientation and professional affiliation may contribute to the devaluation of other points of view.

Although specialization itself is not always bad news—great strides are made when people focus intently on one thing—problems do arise when there isn't a mode by which to bring insights and understandings from different points of view into a useful relationship with one another. The inability of professionals and intellectuals to think from multiple perspectives, and to grant validity to competing perspectives, can indeed have a negative impact when working with complex individual problems and when conflicting ideas of the “real” contend with one another in the larger arena of human history (Wilber, 1995).

The Integral model represents a constructive response to overspecialization and positions itself as a kind of “next step” in intellectual dialogue and practical application. It looks to step back and identify general principles that can help reintegrate or draw meaningful connections between different disciplines. More specifically, it argues that there are many connections to be made between different schools of psychotherapy, different approaches to spirituality, as well as between the hard sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry), soft sciences (e.g., political science, economics), art, and morality. To make this somewhat clearer, and without getting too far ahead of ourselves, the basic gist of Integral philosophy is as follows:

-

What is real and important depends on one's perspective.

-

Everyone is at least partially right about what they argue is real and important.

-

By bringing together these partial perspectives, we can construct a more complete and useful set of truths.

-

A person's perspective depends on five central things:

-

The way the person gains knowledge (the person's primary perspective, tools, or discipline);

-

The person's level of identity development;

-

The person's level of development in other key domains or “lines”;

-

The person's particular state at any given time; and,

-

The person's personality style or “type” (including cultural and gender style).

The shorthand for these aspects of the Integral viewpoint is often called AQAL, which stands for all quadrants, all levels, all lines, all states, and all types.

To illustrate this further, let's consider a therapeutic situation with a depressed, single, working mother who reports having discipline and behavior issues with her strong-willed, 4-year-old son. Imagine the mother consults four different therapists. The first therapist meets with the mother individually to dialogue about her feelings about parenting and her history with her own parents. This therapist recommends a longer course of therapy for the mother in order for her to work through her own family-of-origin issues. The second therapist takes a more behavioral approach, viewing the mother–child interaction through an observation window. Therapist 2 offers the mother basic communication skills and advice on how to set boundaries and structure their playtime together. A third therapist, a psychiatrist, looks primarily at familial genetic and temperamental dispositions, suggesting that the mother might benefit from medication and exercise because of her depression. Therapist 4, perhaps a social worker, notes how financial issues are placing strain on the mother and hopes to empower her economically and educationally through connecting her with resources in the community.

Now let's also consider that these therapists may be different in other ways besides orientation and the types of interventions they recommend. One might be more psychologically mature than the others. One might have been depressed lately. One might have been born and raised in Japan, whereas the others were born and raised in the United States. The Integral approach suggests, in short, that each of these therapeutic orientations and interventions, as well as each of these individuals, has something very important to contribute to the view of this one client. Indeed, we can bring their insights and interventions together in an organized and complementary way.

Four-Quadrant Basics

So what would it be like if we took for granted that each one of these therapists had important truths and important recommendations to offer? And how would we organize those truths and the accompanying interventions without getting overwhelmed? The best way to begin to understand how Integral Theory conceptualizes this multiperspectival approach is to start with the four-quadrant model. This model serves as something of a meta-narrative for Integral Theory—it is the backdrop on which everything else sits. It also informs our first principle of Integral Psychotherapy.

Principle 1: Integral Psychotherapy accepts that the client's life can be seen legitimately from four major, overarching perspectives: subjective–individual, objective–individual, subjective–collective, and objective–collective. Case conceptualizations and interventions rooted in any of these four perspectives are legitimate and potentially useful in psychotherapy.

The four-quadrant model suggests that there are four basic perspectives humans take on reality. When humans ask the question, “What is real, important, and true?” they tend to answer most often from one of these four major perspectives. Although each of these perspectives is considered legitimate in the Integral view, they also are different in important ways. Depending on the perspective one takes, one will describe phenomena differently and use different methods to gather and evaluate evidence.

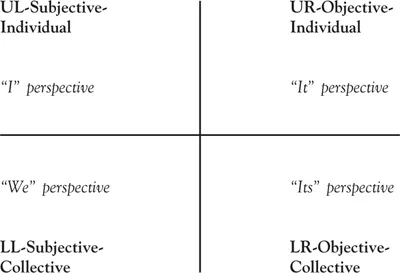

The first major distinction made in the four-quadrant model is between viewpoints that look at things subjectively, or from the interior, and objectively, from the exterior. The left side of the model represents the subjective, whereas the right side represents the objective. The second major distinction is made between the individual and collective perspectives. The individual perspective is represented in the upper half, and the collective in the lower.

For example, in psychotherapy some people look primarily at the client's subjective (or intrapsychic) thoughts, feelings, and memories as being the cause of a particular issue. This is a subjective-individual perspective, or upper-left (UL)-quadrant perspective. Others argue the importance of understanding people by looking at intersubjective relationships, most notably familial, intimate, and community (cultural) relationships. This is a subjective-collective perspective, or lower-left (LL) quadrant perspective.

In contrast, some therapists tend to look to the person's biology and genetics when trying to understand issues of mental health. This is an objective-individual perspective or upper-right (UR)-quadrant perspective. Behavioral approaches, for reasons we will touch on later, also fall into this category. Finally, there are other therapists who emphasize the sociopolitical situation of the client and his or her access to systems such as political representation, health care, education, and housing. This is an objective-collective perspective or the lower-right (LR)-quadrant perspective. For a visual overview of the four-quadrant model, see Fig. 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Basic Overview of the Four-quadrant Model

To review and add a bit to each, the four quadrants can be broken down in the following way:

The UL quadrant represents the subjective-individual. This is the first-person perspective or the perspective of “I.” The most important mode of knowing from this perspective is direct phenomenological experience—what the person experiences in thought and emotion that only he or she can access directly. As we will discuss further, this quadrant addresses the client's stage of identity development, state of consciousness, mood, affect, cognitive schemas, fantasies, and memories.

The LL quadrant represents the subjective-collective. This relates to the second-person perspective or the perspectives of “we”—those shared values and meanings that can only be accessed through dialogue and empathy between people. In terms of psychotherapy, this quadrant addresses the client's intimate relationships, family experience, and cultural background and values.

The UR quadrant represents the objective-individual, or the third-person perspective of “it.” Knowledge from this perspective is gained through various empirical measures such as biology, chemistry, neurology, and so forth. These methods are sometimes called monological (Wilber, 1995), meaning that they don't require dialogue—information is gathered through impersonal observation. Behavioral interactions are included in this quadrant because behavior can be observed from the outside without reference to thoughts, feelings, or empathy (i.e., one can observe that a school-aged child disrupts class with inappropriate behavior without having a conversation about it). Overall, this quadrant addresses the client's genetic predisposition, neurological or health conditions, substance usage, and behaviors (general, exercise, sleep, etc.), among other things.

The LR quadrant represents the objective-collective, or the third-person perspective of “its.” This includes the functioning of ecological and social systems, which also can be understood through impersonal observation. More specific to our topic, the issues addressed here focus on the external structures and systems of society. The socioeconomic status of the client, work and school life, and the impact of legal, political, or health-care systems are included. The natural environment would also be considered an important factor in the life of the client from this point of view (i.e., the client's access to nature and to clean water, air, etc.).

Additional Aspects of the Four-Quadrant Model

Now that we have laid out the basics of the model, we need to emphasize two other aspects of four-quadrant theory that will help guide the rest of the text.

The first additional point is that the four quadrants can be seen to be four c...