![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Shōfujin (Little Women)

Re-creating Jo for the Female Audience in Meiji Japan

In 1868, after over 200 years of isolation, Japan ended the feudal system and opened its borders to other countries, ushering in a period of rapid westernization and industrialization. This same year saw the publication in America of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888),1 daughter of Amos Bronson Alcott, a leading figure of the American transcendentalist movement.2 The heartwarming story of the four March sisters’ growth into womanhood at the time of the absence of their father during the American Civil War is a semi-autobiographical work. It became a best seller and created a sensation on the American literary scene, proving to the public that a woman could be successful in the male-dominated world of the publishing industry.3 Little Women’s reputation traveled around the world, and the work was translated into various languages, including Japanese.

This section will examine Shōfujin, the first Japanese translation of Little Women, to see how its female translator strove for the best means to render the world of the novel without deviating from Meiji cultural female codes and to fulfill her directive to deliver the ryōsai kenbo educational ideology. The translation nevertheless conveyed the potential of adolescent girls through its introduction of the ambitious heroine, Jo March (translated as Shindō Takayo) to the young female Japanese audience.

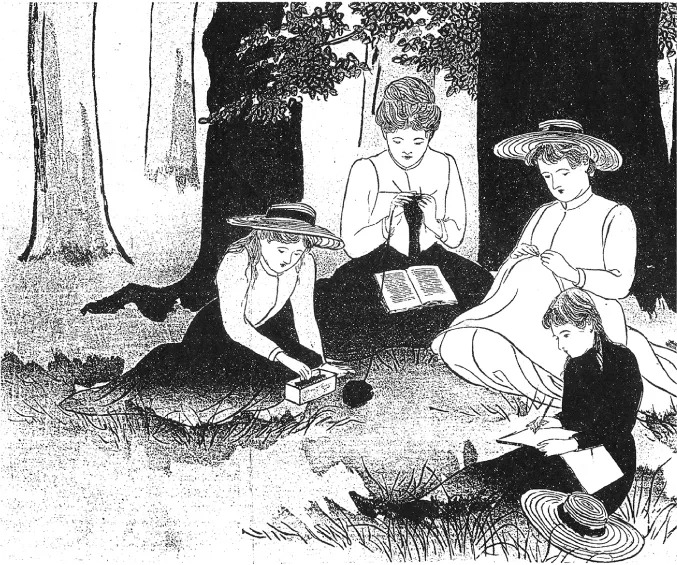

As early as 1897, Louisa May Alcott was introduced as the most celebrated American fiction writer in Jogaku zasshi in Japan.4 Shōfujin5 was adapted in 1906 by a novice female translator named Kitada Shūho.6 Kitada must have been a well-educated woman. She might have been an artist, judging from the fact that an illustration in this book is drawn by Kitada. Unfortunately, no information about Kitada is available today. Although hers was the first translation of the book, Little Women has been translated many times since then, usually under the title Wakakusa monogatari (Stories of Young Grass),7 and the fact that Kitada’s version exists is hardly known. Shōfujin is not a skillfully translated work. However, when viewed in the light of the Meiji era, this abbreviated translation can teach us much about girls’ education during that period.

Figure 1.1. Front cover of Shōfujin. The text on the upper right credits forewords by Tsubouchi Shōyo and Aeba Kōson. The publisher’s name, Saiunkaku, is written on the left. The stamp on the lower right indicates the date, December 28, 1906, when a copy of the book was provided to the Imperial Library by the Department of the Interior. Courtesy of Kokuritsu Kokkai Toshokan.

Good Wife, Wise Mother Ideology in Shōfujin

Shōfujin was published at a time when girls’ schools were proliferating. Most schools upheld the ryōsai kenbo ideology as their educational goal.8 Women’s ryōsai kenbo education substantially aided the government in the creation of an industrialized and militaristic nation, particularly during the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). Stronger family unity equated to stronger state unity,9 and the wars required women to encourage patriotic sentiment at home. Home life, therefore, was put in service of the state, at the cost of women’s independence. Sharon H. Nolte and Sally A. Hastings state that during these years, “[s]tate propaganda exhorted women to contribute to the nation through their hard work, their frugality, their efficient management, their care of the old, young, and ill, and their responsible upbringing of children. The significance of these functions did not entitle them to political rights, however.”10 They argue that “the Japanese cult of productivity … was significantly different from the American cult of domesticity”11 of Alcott’s era, which identified the home as a female sphere and expected women to be religious and virtuous.12 According to Fukaya Masashi’s research, the ryōsai kenbo ideology was a historical amalgam of Western ideals, Japanese Confucianism, and nationalism.13 Home was designated as part of the nation; the concept of “Familial Nationhood” (kazoku kokkakan) was created, which situated the Emperor as the “father” and the whole nation as one big family. Women were still forced to accept unequal hierarchical relationships in society and confinement to the sphere of domesticity. Not only that, but the ryōsai kenbo ideology taught women their new responsibilities as Japanese citizens. The goal of Shōfujin was not to show women’s domestic power or independence, but to emphasize that their place was in the home, implanting in readers’ minds the awareness that they were not only ie no musume (daughters of domesticity) but also kuni no musume (daughters of the nation).14

Figure 1.2. Illustration for Shōfujin by Kitada Shūho. Courtesy of Kokuritsu Kokkai Toshokan.

Women’s education was strictly for the purpose of domestic reform, a national priority that was explicitly entrusted to women. Gender roles in domesticity came to be defined and demarcated. Child rearing in Japan was not originally defined as a woman’s role.15 Kathleen S. Uno elaborates: “[f]rom the Tokugawa period into the mid-twentieth century, both productive work, which sustained the ie (stem-family household) by producing essential goods and income, and reproductive work (childrearing, cooking, and housekeeping), which maintained ie members, took place at home. The proximity of production and reproduction allowed men, women, and children alike to participate in tasks crucial to the household’s survival.”16

However, in the Meiji era, a division of labor based on gender—husbands working outside the home and wives staying home, in charge of domestic chores and child nurturing—was introduced, defining women as domestic beings. After the Meiji period, domestic work came to be the responsibility of women. Women were to utilize what they had learned at school to manage the chores and home economy as good wives, and, as wise mothers, deliver home education, called katei kyōiku, in order to raise children who would shoulder responsibility for the country’s future. We can assume Little Women was utilized for the development of qualities of ideal womanhood in Japanese schoolgirls.

This educational aspect is emphasized in the two prefaces written by respected fiction writers and translators Tsubouchi Shōyō17 and Aeba Kōson.18 They endorsed Shōfujin as a good home novel (katei no yomimono) worthy of recommendation to its female audience. It is interesting to see that Shōfujin was supported by these significant literary figures.19 Aeba describes this “pure and beautiful” book as suitable for “fujoshi” (young women and children), continuing that “although the translation is careless and still immature, it is unique in the sense that it truthfully portrays innocent little ladies.”20 As literacy increased around the turn of the twentieth century, the target audiences of home novels were women and children, newly emerging readers at that time. Aeba demarcates women’s literature from men’s, “authentic” literature, corralling women and children within the confines of domesticity and segregating them from the mainstream literary world. Despite their favorable views of Shōfujin, an attitude of male patronization by both Aeba and Tsubouchi toward female writers, translators, and readers is evident. Kitada Shūho translated Little Women without deviating from literary conventions or social norms, perhaps doing her best to loyally play her role as a “female translator” for a “female audience.”

Kitada’s statement of the goal of Shōfujin in her preface conforms closely to the principles of ryōsai kenbo.

This book is an abridged translation of Little Women, written by Miss Alcott, who is very famous in the American literary world. The original work is full of great writing. … This beautifully written book should be taken as a home primer which teaches shūshin (morals) and seika (wise governance of family affairs).21

Shōfujin introduced the Japanese female audience to Western lifestyle and the image of a Western home. It also taught female virtues and modern women’s expected roles and enhanced responsibilities at home.

Introduction of the Idea of Western Home and Women’s Roles

The novel contains descriptions of an ideal Western culture from which Japanese people at that time were trying to learn. The parts of the original that touched on educational issues such as women’s virtues and morals were translated faithfully, so that readers could learn and internalize them as they read the story.

The idea of “home” was a focus among intellectuals in nineteenth-century America. The role of the white middle-class American woman prior to 1860 had been encapsulated in the concept of the “cult of domesticity.” While accepting the notion that their position was in the home, women later maneuvered this role into one of power. Daniel Scott Smith states,

[I]nstead of postulating women as an atom in competitive society, domestic feminism viewed woman as a person in the context of relationships with others. By defining the family as a community, this ideology allowed women to engage in something of a critique of male, materialistic, market society and simultaneously proceed to seize power within the family.22

Little Women was written amid this social change. Alcott put forward a new image of young women and illustrated how their powerful and attractive qualities were cultivated at home.23

These ideas of “home” and women’s domestic leadership were new for Japanese in the early Meiji period. The Japanese ie system, based on Confucian principles, originated in the samurai class in the Edo period and came to be institutionalized in a patriarchal sphere controlled by the hierarchized relationships of family members.

The ie is not simply a contemporary household as its English count...