eBook - ePub

Persian Literature as World Literature

Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa, Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 272 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Persian Literature as World Literature

Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa, Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Confronting nationalistic and nativist interpreting practices in Persianate literary scholarship, Persian Literature as World Literature makes a case for reading these literatures as world literature-as transnational, worldly texts that expand beyond local and national penchants. Working through an idea of world literature that is both cosmopolitan and critical of any monologic view on globalization, the contributors to this volume revisit the early and contemporary circulation of Persianate literatures across neighboring and distant cultures, and seek innovative ways of developing a transnational Persian literary studies, engaging in constructive dialogues with the global forces surrounding, and shaping, Persianate societies and cultures.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Persian Literature as World Literature è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Persian Literature as World Literature di Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa, Mostafa Abedinifard, Omid Azadibougar, Amirhossein Vafa in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Literature e Middle Eastern Literary. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Part One

Literary Worldliness

1

The Birth of the German Ghazal out of the Spirit of World Literature

Die Schenke, die du dir gebaut,

Ist größer als jedes Haus.

Ist größer als jedes Haus.

Die Tränke, die du drin gebraut,

Die trinkt die Welt nicht aus.

Die trinkt die Welt nicht aus.

F. Nietzsche

In the fall of 1820, forty-two poems in the style of Persian mystical poet Rumi were published by Friedrich Rückert, the editor of a literary pocket almanac, Taschenbuch für Damen: auf das Jahr 1821. These would be the first German ghazals, heralding a two-year ghazal-publishing frenzy by Rückert and his younger friend and erstwhile collaborator, August von Platen, whose Neue Ghaselen two years later put an end to the literary duel with this epigram: “Der Orient ist abgetan, / Nun seht die Form als unser an” (The orient is done, / now behold the form as ours).1 While Rückert’s Rumi “replicas” were the first ghazals in German, it was Platen who was first to publish original German ghazals and who became “Gaselendichter κατ’ εξοχήν,” ghazal-poet, par excellence!2

Despite the intensity and relative prosodic success of Platen’s campaign to make ghazal German, save for some limited application by a few notable poets, the form was largely not used, even when Orientalizing was smart. For example, Friedrich von Bodenstedt’s 1851 Lieder des Mirza Schaffy saw at least one hundred forty editions and many translations, but it seldom uses the ghazal form.3 In fact, today there is little trace of the German ghazal. Judith Ryan’s The Cambridge Introduction to German Poetry (2012) only mentions Platen once, and then in relation to the sonnet, with no mention of Rückert or the ghazal at all. Reflecting on this transient phenomenon we may wonder why the ghazal form did not take root in German literary soil, and what primo loco spurred Platen to not just transfer the ghazals’ contents into German, but also their form.

The post-Napoleonic German national crisis, instead of being resolved by the Congress of Vienna (1815), was extenuated by it, leading to the nobility’s further fall from grace as an agent of brutal repression. The crisis mirrored a spiritual and sensual conflict in Platen’s own subjectivity, provoking his existential need to reflect on what is noble. As courtly love poetry, the Persian ghazal offered Platen something for which he had found no precedent in the Western literary tradition: an anagogic form that could subsume his homoerotic disposition while performatively reframing for the era what the nobility signified beyond rank and wealth.4 That the new transplant wilted on the alternate route taken through bourgeois sentimentality, proletarian class struggle, and aristocratic militarism toward German unification by the century’s end only casts Platen’s project in starker relief.

While comprehensive engagement of Platen’s ghazal oeuvre far exceeds this chapter’s latitude, to highlight the existential importance of this project to him, a line can be traced from Platen’s originary search for a tradition that weds sensuality and spirituality, through the labor of his Persian studies, his painful delivery of the ghazal for his fatherland, and his subsequent death in exile. This quest is nowhere more pronounced than in the infamous Heine–Platen affair, which while liable to be the only thing an average Germanist would know about Platen today, is seldom viewed with an appreciation of its prima causa: an unwitting attack on the ghazal as form. Equally important is to highlight the merit of revisiting these largely forgotten ghazals now as the academic zephyr promises more than ever the sort of polytropic, multidisciplinary research and collaboration that their reception warrants, to make them available to a Persian readership inscribed in them at their birth:

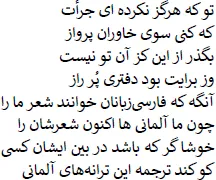

Du, der nie gewagt zu fliegen Nach dem Orient, wie wir, Laß dies Büchlein, Laß es liegen, Denn Geheimnis ist es dir. Wenn einst Perser deutsche Verse Lesen, wie wir ihre jetzt, Dann geschieht’s, daß ein Perser Diese Lieder übersetzt.5 |  |

You, who never dared to fly

To the Orient like we

Let this booklet, let it be

For secret it shall be to thee.

When once Persians German verses

Read, like we do theirs of late,

Then it shall be that a Persian,

These German songs will translate.

In his polysystem theory, Itamar Even-Zohar argues that literary translations introduce into the home literature features that include not just “a new (poetic) language, or compositional patterns and techniques” but also possibly “new models of reality.”6 As we will see, the notion of acquiring a new model of reality is essential to Platen’s project. The degree of such translations’ impact, Even-Zohar argues, is inversely related to the maturity, strength, centrality, or stability of the home literary polysystem. Translations have the greatest impact, he says, when the home literary polysystem is experiencing a turning point, crisis, or a vacuum; and the younger, weaker, and more peripheral it is within the larger literary polysystem wherein it lies.7

Starting in the early eighteenth century, translations from the classical and the more established Romance languages had strengthened the German literary polysystem such that by Rückert and Platen’s time, its position within the European polysystem had already become more central. By 1819, when Goethe published his Divan, the German literary polysystem, while still not as strong as the French, was not anymore young, weak, or peripheral. And yet, the German system experienced a pivotal and existential crisis both on the political and the literary level.

The French Revolution, then the Napoleonic Wars, and the subsequent “German wars of liberation” (1813–14) stirred a sense of unity, fraternity, and hope, only to be crushed at the Conference of Vienna (1814–15) which restored the pre-Napoleonic order and formed a loose German confederation, Deutscher Bund. The Burschenschaften (university fraternities), formed at this time, became centers of political agitation by Platen’s first semester at university when the Bund ratified the Carlsbad Decrees (1819) to limit political activity. There was a ubiquitous murmur: whither Germany?

Spiritually, for a century, the Enlightenment had impelled a gradual secularization that many in Platen’s time experienced as spiritual dearth. By the end of Weimar Classicism in 1805, the humanist wells of inspiration seemed sapped; and the initially theoretical and later literary German Romantic movement had similarly bled their medieval resources dry in a quest for homespun organic spirituality. Now, by the late 1820s, all had coalesced into a lethargic world of ennui and melancholic Weltschmerz. This is where Rückert and Platen found themselves when they started writing ghazals. It is ironic that the prodigious Goethe, a culprit in this exhaustion, would also show a way forward by his practical engagements with extra-European literature, and in time, his concept of Weltliteratur.8

The two sides of the German national crisis, the fading aristocracy and the rising bourgeoisie are remarkably well personified by the two erstwhile collaborating ghazal-smiths. The future Professor Rückert who would translate from some forty-four languages, was a patriot and a family man with a strong sense of community and fraternity.9 But his famous motto, Weltpoesie allein ist Weltversöhnung (world-poetry alone is world-reconciliation), distinguishes him from Platen, for whom reconciliation with the world was not quite as easy.10

Platen: Poros and Penia

It would be misleading to say that Karl August Georg Maximilian Count of Platen-Hallermünde’s lineage reached three major European royal houses, since both he and his father were products of second marriages, and thus doubly removed from principal inheritance.11 His mother had moreover raised him on the proto-Romantic and republican precepts of Rousseau’s Émile, and introduced him early to the French and other Romance-language literary traditions. Platen’s diary, which he kept in some twelve languages, was modeled after Rousseau’s Les Confessions.

Prussia had just ceded Platen’s hometown of Ansbach, to Bavaria, when the insolvent aristocrat youth, with no prospect but to enter the service of a prince, was enrolled at the Bavarian Military Academy. The estrangement and displacement felt by the north-German-accented Prussian-Lutheran boy in the ghastly barracks in Catholic Munich would only multiply soon thereafter when he would come to recognize in himself what we today call homosexuality and try to reconcile it with the prevalent conventional Christian mores of his age, which reduced his feelings to their crassest expression. Inspired by Rousseau, he always favored over rationality the truth of subjective feelings, the expression of whose reconciliation with faith, through his poetic temperament, would ever override public prudence.12

Early on, fellow cadets were the Erato for Platen’s poetic finger practices. In time, alongside his change in stations, cadet-muses turned to courtiers, officers, and later students. But a type united all of them: physical vigor and splendor checked with some want of literary learning and the need of a peer’s loving mentorship. Most importantly, these boys and later men seldom recognized the heart-wrenching poetry they stirred in their casual acquaintance who sometimes held forth on the sacred beauty of the loving friendship among men. In conforming to a neo-Platonic convention as the most prevalent form of such expression, this early framing unwittingly flouts actual physical sensuality, and later primes a search within the Western tradition for any precedent aesthetic poesis to express Platen’s inextricably tangled spiritual and sensual homoerotic sentiment. The resulting existential research soon fostered a prosodic virtuosity that traversed the German language’s limits and productively engaged ever greater n...