![]()

ONE

From Notches to Tablets

A history of writing should be predicated on an understanding of what constitutes ‘writing’. The proposition is not so simple. Most readers familiar with only one consonant-and-vowel alphabetic writing system – conveying spacially separated ink-printed letters in divided words from left to right in descending horizontal lines – will perhaps be only faintly aware that the world of writing embraces so much more.

Communication of human thought, in general, can be achieved in many different ways, speech being only one of them. And writing, among other uses, is only one form of conveying human speech. Nevertheless, modern society, it appears, has exalted this distinctive form of communication. Perhaps this is partly because, as a representation of external realities, communication through graphic art seems more objective, more substantial, than linguistic communication.1 Even abstract notions can be transcribed graphically through this ‘solidifying symbolic system’. The roots of this system are to be found in human beings’ fundamental need to store information in order to communicate, whether to themselves or to others, at a distance in time or space.

Since one knows writing only for what it is now, it is difficult – perhaps even pointless – to provide a definition of it that presumes to include all past, present and future meanings. Whether it is of utilitarian advantage to see in ‘full’ writing a ‘system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought’2 is a moot point. Just as valid would be the equally unspecific definition of writing as ‘the graphic counterpart of speech, the fixing of spoken language in a permanent or semi-permanent form’.3 Yet this, too, seems to miss so much of what writing is about. One might accept that it is indeed the sequencing of standardized symbols (characters, signs or sign components) in order to graphically reproduce human speech, thought and other things in part or whole. This might, in fact, be the most general definition of writing possible at present. How well each system then accomplished this in the past was determined by the relative need of each society as it grew more complex. But this definition, too, remains just this: a limiting definition of something rather special that appears to resist limitation.

It may be best to avoid the ‘pitfall’ of a formal definition altogether, as writing has been, is and will be so many different things to so many different peoples in so many different ages. Instead, for the immediate purpose of this history of writing, one should perhaps address the more relevant question of ‘complete writing’, here defined as the fulfilment of three criteria:4

Complete writing must have as its purpose communication;

Complete writing must consist of artificial graphic marks on a durable or electronic surface;

Complete writing must use marks that relate conventionally to articulate speech (the systematic arrangement of significant vocal sounds) or electronic programing in such a way that communication is achieved.

Every graphic expression that constitutes early writing – early writing fulfils at least one, but never all, of these three criteria – can be regarded as ‘writing’ in its largest sense, though it remains ‘incomplete writing’. Some sort of communication is taking place, albeit of a limited, localized and/or ambiguous nature.

Writing did not emerge from nowhere. Divine provenance has been many peoples’ preferred cliché. In fact, this fiction survived in Europe well into the 1800s, and is still embraced by certain communities in the US and in Islamic countries. Others have asserted that complete writing – writing fulfilling the three criteria – was ‘invented’ around the middle of the fourth millennium BC by a Sumerian in Uruk consciously searching for a better method to deal with complex accounting. Others see complete writing as the result of group effort or accidental discovery. Still others believe complete writing to have had multiple origins, for various reasons. Then there are those who assert that complete writing is the product of a long evolution of early writing over a wide region of trade.

There is certainly no ‘evolution’ in the history of writing, not in the sense the word generally conveys. Writing systems do not change of their own accord in a natural process; they are deliberately elaborated or changed by human agents – drawing from a wide variety of existing resources – in order to achieve any number of specific goals.5 Perhaps the most common goal is the best graphic reproduction of the writer’s speech. Constant small changes to a writing system’s script over many centuries, even millennia, will result in enormous differences in that script’s later appearance and use.

Before complete writing – that is, before the fulfilment of the three criteria – many processes akin to writing obtained. However, to call these processes ‘proto-writing’6 would perhaps be to award them a status and/or role they do not deserve and never fulfilled. On the other hand, pictography (‘picture-writing’) and logography (‘word-writing’, whereby the depicted object is to be spoken aloud) might justifiably be called ‘pre-writing’. Elaborating on nineteenth-century German speculations, American linguist Leonhard Bloomfield distinguished in the 1930s between ‘picture writing’ and ‘real writing’, with the latter also fulfilling certain essential criteria (signs had to represent linguistic elements of some kind, and be limited in number).7 A distinction has also been drawn between primitive ‘semasiography’ (whereby graphic marks convey meaning without recourse to language) and ‘full writing’, with only the latter to be regarded as writing in the ‘true’ sense.8

Whatever one’s formal position regarding early writing attempts, graphic expression appears to be a very ‘recent’ phenomenon among hominids: the earliest ‘engravings’ appear to date from about 100,000 years ago (some say much earlier). However, our ancestors’ regular series of incised dots, lines or hatch marks (allegedly tallies or lunar calendars) in no way suggest a link to articulate speech – though these ‘proto-scribes’ certainly spoke as fluently as we do today.

Before complete writing, humankind made use of a wealth of graphic symbols and mnemonics (memory tools) of various kinds in order to store information. Rock art has always possessed a repertoire of universal symbols: anthropomorphs (human-like figures), flora, fauna, the Sun, stars, comets and many more, including untold geometric designs. For the most part, these were graphic reproductions of the commonest phenomena of the physical world. At the same time, mnemonics were used in linguistic contexts, too, with knot records, pictographs, notched bones or staffs, message sticks or boards, string games for chanting, coloured pebbles and so forth linking physical objects with speech. Over many thousands of years, graphic art and such mnemonics grew ever closer in specific social contexts.

Eventually, they merged, to become graphic mnemonics.

KNOT RECORDS

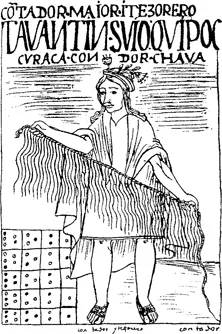

One of the ancient world’s commonest mnemonics was the knot record, which dates back at least to the Early Neolithic (the last period of the Stone Age).9 Such records could be simple knots in a single strand or complicated series of colour-coded knots on strings attached to higher-order strings. Knot records reached their peak of development, it appears, with the Inca’s quipus (illus. 1). These comprised an elaborate means of counting: different knots in various positions depicted numerical quantities, the knots’ colours representing, it has been alleged, individual commodities.

The Inca of ancient Peru used mnemonics almost exclusively to achieve what writing achieved in the same or similar contexts in other societies. The Inca had several different types of knots to record their empire’s daily and long-term mercantile transactions and payment of tribute. Each knot held a specific decimal value (no knot in a certain place meant ‘zero’). For example, one overhand knot above two overhand knots above a group of seven knots recorded the number ‘127’. Thus, there were specific cord places for the concepts ‘hundreds’, ‘tens’ and ‘ones’. Bunches of strings of knots could be tied off with summation cords. A special class of quipu-reading clerks oversaw and managed this highly complicated and efficient system. Even after the Spanish conquest of the 1500s, the quipu was retained for daily record-keeping.

1 The quipu of an Inca imperial accountant. From Félipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, Nueva crónica y buen gobierno, c. 1613.

Though not as elaborate as those of the Inca, similar prehistoric quipu can be found from Alaska to Chile; indeed, they are the Pacific Rim’s indigenous record-keeping system. The South-East Marquesan tuhuna ‘o’ono bards, for example, used bundles of woven coconut fibre from which hung small strings of knots called ta ‘o mata that could also be used to enumerate generations. On ancient Ra’ivavae in the Austral Islands, south of Tahiti, genealogical records were kept by means of knotted hibiscus-bark cords. Similar phenomena can be found throughout the world. In his Scythian campaign, the Persian king Darius left Greek allies guarding a rear bridge with instructions to untie one knot in a 60-knot thong each day: if they finished untying all 60 before his return, they were to sail home to Greece. Knot records are a much more versatile mnemonic than simple tally sticks or notched staffs. Permitting greater categorical variety and complexity, they can easily be ‘erased’ or ‘rewritten’ by mere retying.

Some scholars claim that these knotted strings or cords were the only primitive form of ‘writing’ developed in the Andes.10 But phonetic writing did apparently exist there (see Chapter 6). And knotted strings do not comprise writing. They are memory prompts. Though the knots’ purpose is communication, they are not artificial graphic marks conveyed on a durable surface, and their use has no conventional relation to articulate speech.

NOTCHES

Slashes in the bark of a tree – like rocks placed on a grave, branches rearranged over a path or an ochre handprint on a rock face – represent ‘idea transmission’. That is, they communicate something to others beyond immediate hearing. Here, marking and mnemonics were often combined to produce marking as mnemonics. The idea is extremely old, possibly older than the earliest known cave art.

Perhaps even Homo erectus used notches as mnemonics. Artefacts unearthed at Bilzingsleben in...