eBook - ePub

A Pocket Guide to Christian History

Kevin O'Donnell

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 224 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

A Pocket Guide to Christian History

Kevin O'Donnell

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

An accessible, down-to-earth introduction to the central aspects of Christian history, this Pocket Guide includes the stories of its key events and characters, bringing a wide range of chronological, geographical and doctrinal history vividly to life. From the early church to the twenty-first century, this concise and fascinating book is a lively survey of the world's most widespread religion. Covering topics as diverse as the Apostles and Constantine, the Celtic Church and the division between East and West, the Reformation and the Enlightenment to the modern age, this is an indispensable resource for understanding a truly global phenomenon: Christianity.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

A Pocket Guide to Christian History è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a A Pocket Guide to Christian History di Kevin O'Donnell in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Theologie & Religion e Kirchengeschichte. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1. After the Apostles – The First Century AD

The Acts of the Apostles, the New Testament account of the rise of the early church, ends with Paul awaiting trial after his appeal to the Roman emperor, a right to which he was entitled as a Roman citizen. All that the text tells us is that ‘For two whole years Paul stayed there in his own rented house and welcomed all who came to see him. Boldly and without hindrance he preached the kingdom of God and taught about the Lord Jesus Christ’ (Acts 28:30–31). We hear no more of him in the pages of the New Testament, but history reveals that events were to take a turn for the worse in Rome. The earliest ‘Christians’ were Jews and thus they were under the protection of the empire, as Judaism was tolerated, and exempted from the laws about sacrificing to Caesar or the pagan deities. However the situation altered as the number of Gentile converts increased.

When Rome suffered a tremendous fire in AD 64, the emperor Nero used the Christians as scapegoats. Many were horribly persecuted, being crucified or thrown to the wild beasts. The apostles Peter and Paul were probably martyred during this time. The Jewish revolt of AD 66–70 ended with the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans in AD 70; Christian operations moved to mainland Europe and toleration wore thin.

Apostles and martyrs

Jesus called twelve men to be his followers (as described in Mark 3:13–19). At first they are referred to as the twelve disciples, from the Latin version of the Greek word mathētēs meaning ‘learner’ or ‘student’. Latterly, after the establishment of belief in the resurrection of Jesus, they are known as the apostles.

An apostle was one sent out with authority, an ambassador bearing the seal of the king or emperor. The transition from one to the other is a remarkable detail of Christian history. To some, Jesus seemed to have failed as he was executed on a cross. Most of his disciples fled and deserted him, losing their faith. But something galvanized them, turning them around and renewing their belief. The gospels relate that this event was the resurrection of Jesus, a mysterious, elusive event that is attested in various narratives and is affirmed in the rest of the New Testament as the pivotal event that birthed the church.

The biblical apostles were leaders of the early church, standing in for Jesus, seeing themselves as his delegates. Some of the apostles and early believers were martyrs (from the Greek word martyrion meaning ‘witness’). One who gave his or her life for the faith was a ‘martyr’ par excellence, and according to church tradition many of the apostles were martyred, although the only martyrs mentioned in the New Testament were Stephen the deacon (Acts 6–8) and James, the brother of John (Acts 12:2). Nothing is known about the fate of some, but there is a cluster of traditions about other apostles. There is little hard evidence and much that we do not know, as only certain things were written down. After the New Testament there are scattered references in later writings of the church fathers such as Eusebius (c. AD 260–340) who wrote his Ecclesiastical History after the emperor Constantine’s conversion. However, there are many legends and oral traditions, which probably contain at least some truth. Sometimes these are varied and contradictory, but the list below is a summary of the main traditions about a number of the apostles.

Some wonder what would have happened if the church had gone east rather than west. It did, in part. Besides following the trade routes of the Roman empire across North Africa, into Europe and Rome itself, missionaries found their way into the Persian empire (modern-day Iran and Iraq) and further afield at least as far as India. (Later Christians followed the old silk route into the Far East and China.) However the power of Rome and its widespread empire with an excellent system of communication meant that the church in the West was to have more widespread and lasting influence in history.

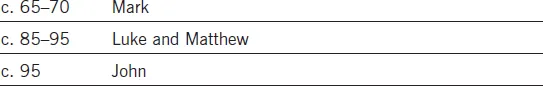

The four Gospels – sources of the Christian story

The exact date of the composition of the four Gospels is unknown and is a matter of conjecture by scholars. Certain parameters help us, such as the end of the first century when Clement of Rome quoted from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew (c. AD 95) and saw these verses as scripture. A fragment of John was found in the sands of Egypt which is dated between AD 110 and 130; allowing time for this to be copied and circulated and to gain authority, it must have been written no later than the end of the first century. Scholars usually suggest the following chart of dates:

Some have suggested earlier dates, such as Bishop J. A. T. Robinson, who argued that all the Gospels predate AD 70 as none explicitly mention the fall of the Temple in Jerusalem. His views, however, have not been widely accepted. Belief in the testimony of the apostles behind the sayings and narratives in the Gospels has ancient pedigree. Early Christian writers such as the early second-century bishop Papias of Hierapolis argued that Matthew wrote the logia (sayings) in the Hebrew tongue rather than in Greek, and that Mark was the interpreter of Peter. Papias also testifies to a living oral tradition that told and retold the stories and the teachings alongside the written books, ‘I supposed that things out of books did not profit me so much as the utterances of a voice which lives and abides.’2 We would do well to remember that the ancients were more adept at oral transmission in a pre-literate culture. One Jewish rabbi said, ‘A well-trained pupil is like a well-plastered cistern that loses not a drop.’

The Jews, Rome and the Christians

Persecution was recurrent in the first few centuries of Christianity, and it came firstly from some of the Jewish leaders, who saw the early Christians as troublemakers and heretics. The first Christians were Jews who had no idea of forming a new religion but rather were seeking to fulfil and renew their own. At the time, they would have been seen as one of various messianic groups that came and went. Tensions in Judea meant that the Sanhedrin were afraid of the Romans intervening to put down any revolts as they could be ruthless. The Sanhedrin was suspicious of the new Jesus movement; after all, its founder had been crucified by the Romans as a criminal.

The Jewish revolt of AD 66–70 saw the fall of Jerusalem and the end of the Sanhedrin’s power. This might have eased relationships between Jewish followers of Jesus and their co-religionists, but, in fact, some Jewish attitudes to the Christians hardened as the Pharisees survived the fall of Jerusalem and codified traditions and oral laws, defining Judaism for years to come and excluding Christian ideas and versions of Judaism. Also, the flight of Christians from Jerusalem before its fall, when Symeon, the cousin of Jesus, had led them out to the hill town of Pella, had caused mistrust. By the time of the Jewish Council of Jamnia in AD 85, Christians (also called ‘Nazarenes’) were declared heretics, though some did still attend the synagogues but could take no official role. To make matters worse, Christians saw the destruction of the Holy City as divine judgment.

The Roman persecution of the Christians began with Nero’s bloodthirsty attack after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64 but it was not in evidence again until the end of the first century. Some argue that their apocalyptic preaching about the end of the world and the fire of God’s wrath made them suitable scapegoats for the fire of Rome. The early second-century writers Pliny the Younger and Cornelius Tacitus shed some light on how the believers were seen. Cornelius Tacitus wrote:

Christus, from...