eBook - ePub

Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for Gifted Learners

Joyce VanTassel-Baska, Ariel Baska

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 312 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for Gifted Learners

Joyce VanTassel-Baska, Ariel Baska

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This updated third edition of Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for Gifted Learners:

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for Gifted Learners è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for Gifted Learners di Joyce VanTassel-Baska, Ariel Baska in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Bildung e Bildung Allgemein. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Part I

Gifted Education

Models, Standards, and Identification

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Curriculum Planning and Instructional Design for the Gifted Learner

Setting the Course

DOI: 10.4324/9781003234050-2

In Latin, the word curriculum literally means “racetrack.” Every good Roman charioteer knows that a good curriculum means a solid and propitious racetrack. At the end of the school year, many teachers may feel that they have just run a race, one with laps indicated by marking periods, interims, and grade reports. And the quality of the racetrack may not have been to their liking, nor satisfied the needs of their chariot riders. The end of a year marks the beginning of planning for the next, whether in racing or schooling. Thus, a strong curriculum is the key to improvement in teacher-student learning performance.

The act of planning involves complex mental and behavioral operations to reach goals. People plan in order to solve problems, correct mistakes, and anticipate the future. For educators tasked with designing curricula for the gifted, this book will guide them through the process of curriculum design and instructional planning based on current standards and elements of differentiation.

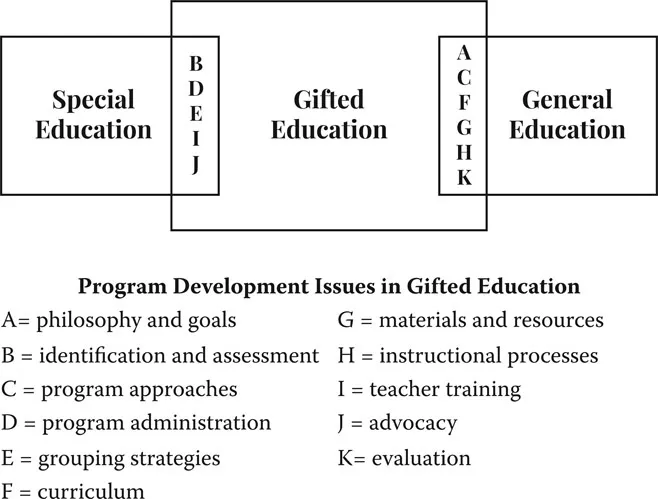

Gifted educators must be aware of the field’s history and the context into which gifted programs and curriculum are being designed. Schools are organized to address the needs of all learners with some considerations for accommodations for students with special needs and adaptations in the curriculum for gifted learners through differentiation. In this book, general education refers to the educational curriculum practices used for the majority of students, including all basic and core curriculum requirements. Special education refers to the field of education that specializes in exceptionalities related to disabilities, including learning disabilities, emotional and behavioral disorders, physical disabilities, and developmental disabilities. Gifted education refers to the programs and services provided to advanced and gifted learners in specific domains of learning.

From the Perspective of History

Gifted education is at a crossroads with respect to its next stage of development. Since the mid-1970s, growth of the field at the grassroots and state levels has been phenomenal. Even with a lack of federal visibility and support during Ronald Reagan’s administration, the field grew, offering more direct services to gifted learners and more opportunities for teacher training and professional development for other school personnel. In the later years of the 20th century and into the 21st, new challenges awaited the field, as gifted education was often left out of both the rhetoric and the educational plans in the era of No Child Left Behind (2001). Gifted students’ needs did not fare well in this period of time. Looking ahead, however, the viability of gifted education depends on forging strong links with existing structures in education, forming partnerships in key areas, and taking advantage of the best that general, special, and gifted education research and best practice paradigms can offer.

Historically, the field of gifted education has used the special education model as the basis for nascent efforts for program development. Identification and assessment practices, teacher training, and administrative program models have all been derived from special education. Gifted education has also attempted to incorporate much of the special education rhetoric in its advocacy for gifted children, speaking of the special needs of the population, appropriate placements, and categorical considerations. Use of the special education model has led to growth and development of the gifted education field over the past 50 years at the grassroots level, yet the special education model may be limited in the very areas in which gifted education is in greatest need of development—curriculum, instructional materials, and assessment of learning.

Special education lacks applicability to a new paradigm grounded in talent development in domain-specific areas of the curriculum (Olszewski-Kubilius, Subotnik, & Worrell, 2018). This paradigm, based on theories of advanced development and expertise, has begun to reshape work in curriculum to ensure that curriculum is content-based and recursive, leading gifted students to new levels of challenge as soon as they are ready.

The Reality of Today

Today gifted education must still relate to two educational worlds: (a) the special education world, representing the language and deeds of responding to special needs learners and providing a continuum of services necessary for such learners, and (b) the general education world, representing the curriculum and organizational support structures that underlie schooling for all learners. Gifted educators must find ways to appropriately negotiate these worlds so that program development efforts for the gifted can move to a higher level of operation.

Gifted education program models for elementary school students have used almost exclusively the special education paradigm for development. Programs at the elementary level have begun with the identification of the target group for services, development of placement services for this group, and allocation of trained teachers to work with these students within schools, but often outside the classroom in a pull-out or special class setting. The nature of curriculum and instructional intervention has frequently been the lowest priority on the list until the last decade. Additionally, gifted education has adopted the special education resource teacher model at the elementary level, which leaves the programs understaffed, based on differences between the fields in per pupil allocations. Typically, special education teachers, for example, have no more than 70 students assigned to them. Elementary resource teachers of the gifted, however, may have 300 or more students. Special education operates on an individual child model through either Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or 504 plans that designate target areas of need for instruction. Gifted education, based on limited resources, tends to work with cluster groups or classes of learners on an advanced curriculum course of study. These differences also make it difficult for the two fields to share a common delivery method, even as schools are addressing the Response to Intervention (RtI) approach with both types of learners (Coleman & Johnsen, 2013). Without the provision of additional resources for serving gifted students, the parity of the model is not in place, leaving gifted learners without appropriate services.

At the secondary level, however, mild content acceleration in math and enrichment in all other subjects has been the point of departure in curriculum development, using the standards as a baseline in program design. Most gifted secondary programs are hybrid models of traditional honors classes in middle school and early high school in arbitrary subjects that are determined by principals or superintendents. In some districts, only math has separate advanced classes. At the senior secondary level, Advanced Placement (AP) coursework is typically offered, with some states requiring at least three different subject area courses be offered (National Association for Gifted Children [NAGC] & the Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted [CSDPG], 2015). Some districts also offer International Baccalaureate (IB), a program designed to advance 11th- and 12th-grade students to the level of college sophomores through an integrated course of study.

The elementary-secondary split in how gifted programs have developed illustrates how gifted education has had to conform to models developed in other areas of education, as well as the difficult choice of using an administrative delivery model developed for special education in a program that lacks the resources to emulate it.

If gifted education is to advance, gifted educators need to embrace the world of general education, its models, and its curriculum standards, while not forsaking the exceptionality concept that defines the nature of the gifted population. Sound curriculum practices for gifted learners must be built on a research base of the latest developments in teaching and learning, motivation, and child development, as well as on gifted education’s own history of effective curriculum models. Figure 1 demonstrates the interrelationship of these three spheres.

An Ideal Planning Model

Friedman and Scholnick (2014) suggested that planning involves essential psychological components, such as representation, sequencing, attention, and self-regulation, which are moderated by expertise in a knowledge base and motivational variables, such as values and coping skills. Also affecting planning, according to this model, are key aspects of the task itself, such as its complexity, coherence, and familiarity, and whether it can be undertaken individually or in groups. These aspects of planning are moderated by the environmental context, which determines the provision of resources, reassurance, and support, and the existing norms affecting coordination of the plan. For several reasons, this planning model provides a useful backdrop for educators planning curriculum experiences for gifted learners.

First, Friedman and Scholnick’s (2014) model acknowledges the important role of curriculum planners and the knowledge, skills, and attitudes they must possess. Educators who engage in curriculum planning for the gifted must demonstrate the following characteristics, among others:

- knowledge of gifted children, their nature, and their needs;

- knowledge of the planning models to be employed—in this case the Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM; VanTassel-Baska, 1986) for differentiation and the curriculum planning model for organizing the products;

- expertise in written lesson plan and unit development tasks;

- ability to represent concepts and ideas in teaching and learning models;

- strength in sequencing ideas and content for presentation; and

- capability to independently develop, test, and revise curricula.

Not all educators can be effective curriculum developers for gifted learners. Strong curriculum development and planning requires the attention of individuals with the knowledge and skills outlined here.

Second, Friedman and Scholnick’s (2014) model highlights the importance of task analysis as an early step in any planning effort (Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2015). Assessing how complex, broad in scope, and familiar the task is and determining the organizational frameworks required to complete the task are essential elements in curriculum planning for gifted learners.

The scope and complexity of the curriculum planning task may be determined by the levels of planning that will be involved. For example, building a K–12 curriculum framework, which involves negotiating the levels of goals, outcomes, and assessment, is fairly complex in that it cuts across grade levels and subject areas and requires a strong team approach. Developing a unit of study on genetics for sixth graders may be conceived as narrower in scope and less complex with respect to target audience and subject matter. In the latter example, coherence in the unit of study may be better achieved by one curriculum developer rather than several, although review and revision of any curriculum product is desirable.

Third, a strong planning model recognizes the effect of the environment or climate of an educational institution on the curriculum planning effort. If the norms of an institution are for every teacher to develop his or her own curriculum, efforts to bring coherence to curriculum offerings will meet with resistance. And although the provision of monetary resources may show support for curriculum work, resources alone are insufficient for successful curriculum implementation (Henderson & Gornik, 2007). Administrative support also must be present, and a critical mass of the faculty, judged to be at least one third of the staff, must be willing and capable to support the effort.

Roles Performed in Instructional Planning

Four essential roles must be performed during instructional planning for the gifted (Morrison, Ross, Morrison, & Kalman, 2019). The roles do not overlap; each role calls for a different type of expertise.

- Instructional designer: This person carries out and coordinates the planning work. He or she must be competent in managing all aspects of the instructional design process. In school districts, this individual could be a gifted curriculum specialist or a curriculum generalist with skills to cut across levels and subjects in the curriculum.

- Instructor: This person (or member of a team) helps to prepare and carries out the instruction being planned. He or she must be well informed about the learners to be taught, the teaching procedures, and the requirements of the instructional program. With guidance from the designer, the instructor carries out details of many planning elements. Following the planning phase, he or she tries out and then implements the instructional plan. In school districts, this individual would be an experienced teacher of the gifted.

- Subject-m...