eBook - ePub

Another Country, Another Life

Calumny, Love, and the Secrets of Isaac Jelfs

J. Patrick Boyer

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 328 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Another Country, Another Life

Calumny, Love, and the Secrets of Isaac Jelfs

J. Patrick Boyer

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

A young law clerk from England falls in love in 19th-century New York and reinvents himself in Canada.

Quiet Isaac Jelfs led many lives: a scapegoated law clerk in England; a soldier in the mad Crimean War; a lawyer on swirling Broadway Avenue in New York. His escape from each was wrapped in deep secrecy. He eventually reached Canada, in 1869, with a new wife and a changed name. In his new home — the remote wilderness of Muskoka — he crafted yet another persona for himself. In Another Country, Another Life, his great-grandson traces that long-hidden journey, exposing Isaac Jelfs' covered tracks and the reasons for his double life.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Another Country, Another Life è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Another Country, Another Life di J. Patrick Boyer in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Law e Law Biographies. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

LawCategoria

Law Biographies1

Escape from New York

Was there no other way?

An anxious thirty-five-year-old lawyer from one of Broadway Avenue’s biggest firms gazed at the scene around him.

Not even the cooler air of early autumn had been able to refresh New York’s acrid skies or dilute the stench rising from the city’s filthy streets, open sewers, and spewing smokestacks. The whole jammed-up place reeked like a fetid cauldron.

Even so, he still felt the city’s tug. It was here he’d found chances to get ahead. He was enthralled by the exotic mixture of peoples, the pulsating rhythms of the place as ships arrived, buildings rose, and crowds jammed through streets chasing trade and entertainment. New York was a civilized jungle. Here he’d been able to turn dreams into realities.

He let out a slow heavy sigh, then turned and entered the station. He knew there was no other choice.

Boarding the train with him early that September morning in 1869 was a pregnant woman, their little girl, a curly-haired youth, and another woman in her early twenties. Other passengers would never have guessed that this family, dressed almost in Sunday best, was heading for Canada’s wilderness to hack out a home from dense forest. Yet, such was their intent. Nor were they alone in this quixotic quest.

If New York had become a magnet drawing hopeful souls and ragged

refugees from all corners of the world, Muskoka District was the newest, best refuge for anyone needing a further escape or yet another fresh start. In the United States, the Republican Party had come to office in 1860 under President Abraham Lincoln with a pledge of free land for homesteaders willing to open the west, and Ontario’s new government had implemented just the year before, in 1868, an identical policy. Some of those now flocking north were refugees from war, flood, fire, or famine. Others sought sanctuary from family tragedy, a crisis of love, a debt of money, or to escape the arm of the law.

refugees from all corners of the world, Muskoka District was the newest, best refuge for anyone needing a further escape or yet another fresh start. In the United States, the Republican Party had come to office in 1860 under President Abraham Lincoln with a pledge of free land for homesteaders willing to open the west, and Ontario’s new government had implemented just the year before, in 1868, an identical policy. Some of those now flocking north were refugees from war, flood, fire, or famine. Others sought sanctuary from family tragedy, a crisis of love, a debt of money, or to escape the arm of the law.

Even as this New York family’s early morning train steamed north toward Canada, “Captain” Pokorny, a furtive Polish immigrant whose rank was said to derive from prior service in the army of his homeland, was another of those unlikely pioneers seeking refuge in the remote northland. A trusted treasurer of Toronto’s opera company, he’d fetched the Saturday night receipts from the theatre to count the haul, keep it safe through Sunday, then deposit the money Monday at the bank. Instead, he vanished, escaping to Muskoka’s deepest bush in Franklin Township, an all but inaccessible section not yet surveyed, not even open for settlement. The edgy Pole found unpromising rocky land at the furthest end of Peninsula Lake for his out-of-the-way “farm,” a place not to grow crops but escape the law. Pokorny would survive, as a squatter, aided by his wits and a suitcase crammed with cash.

Other desperate individuals heading to Muskoka were not eluding the law but forgetting tragedy. After Henry Bird trained as a milliner at his father’s wool-weaving factories in England, he came to Canada, and before long was operating his own mill on the Conestoga River near Guelph, at least until the entire operation was flooded out by great rises in the river. The following year, severe flooding destroyed his rebuilt mill a second time. Then Bird’s wife, Sarah, their three-year-old daughter, and six-month-old son were all killed in an accident. Devastated, Henry Bird abandoned both God and Guelph and headed to Muskoka. By the early 1870s, he would be operating a new mill at the Bracebridge waterfall.

Whether fleeing to Muskoka for reasons criminal or honourable, whether drawn by opportunism or just a sense of adventure, everyone migrating into the bush was on a quest for some kind of new life.

In time Muskoka would become accessible from all directions thanks to convenient transportation and contemporary communications; but in the 1860s the district was not even the end of the line, it was beyond the end. Loggers only reached Muskoka’s southern edge by the late 1850s. Prospectors hadn’t yet discovered Ontario’s treasure chest of minerals in the northern districts beyond; until they did, no mining towns operated up there so there was no need for railways through Muskoka to haul resources south. By the mid-1860s, a couple of primitive colonization roads were being stubbornly pushed into Muskoka’s unknown terrain, one from the east, another, the south. Only in the mid-1870s would a railway line get as far as Gravenhurst, but then not advance any farther north for another decade. When this family from New York headed to Muskoka in 1869, this frontier district was the remotest place on anybody’s horizon.

New arrivals wanting anonymity for themselves asked few questions of others. They just hoped to cross over from one life to the next, a secular redemption, an unhallowed resurrection, entering a better world without having to die first.

Though people were propelled by urgent need to leave troubles behind, at the same time they found themselves pulled north by the bright prospect of becoming prosperous landowners. This alluring vision of being resurrected as self-sufficient individuals living on good farms of their own was even drawing people with no farming experience whatsoever, to land that was not yet settled, nor even cleared of its tangled forests.

These settlers hoped to cash in on a promise Ontario’s government and its immigration agents were aggressively promoting through speeches, advertisements in American and British newspapers, and the booklet Emigration to Canada: The Province of Ontario, distributed widely in 1869 to publicize Muskoka’s glowing agricultural prospects for new settlers. Whatever gloom haunted their pasts, these pioneers positively glowed as they imagined their hundred acres of “free” land. The Muskoka dream was grounded in the belief that having one’s own farm was the foundation of society and personal self-sufficiency; it promised continuation of a centuries-old pastoral way of life, one not yet dislodged by heavy industry, the growth of factories, and the magnet of living in cities.

Few individuals heading north to Muskoka sought a transformation more complete, however, than this desperate Broadway lawyer. In New York he boarded the train as Isaac Jelfs. In Toronto he stepped off as James Boyer.

Not only was Jelfs abandoning his name. He was forfeiting a long-craved legal career with the politically influential, if increasingly embattled, Broadway Avenue firm of Brown, Hall & Vanderpoel. He was relinquishing his recording secretary’s role with the Episcopalian Methodist Church in Brooklyn. He was abandoning the vice-presidency of the Brooklyn Britannia Benevolent Association, an office to which he’d been glowingly elected in May that year, being presented with a copy of Byron’s poetical works and making, as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “one of his happy speeches on the occasion.”

The real kicker was that he had closed the front door of the Jelfs’s 18th Street family home in Brooklyn for the last time. Overnight, Isaac vanished from the life of his wife, Eliza, and their young daughter, Elizabeth.

The pregnant person on the train was not Isaac’s wife in law, but had become a second wife in reality after she’d first captured his heart at a Britannia Benevolent Association dance one Saturday night several years before. The two-year-old girl on the train was their love child, Annie, whose birth the secretive lovers, Isaac Jelfs and Hannah Boyer, had contrived to leave unrecorded in New York’s registries. Equally absent from official documents was any record of their marriage, since neither in New York nor later in Canada would they ever have a legal wedding.

Jelfs had become embroiled in a risky double life, his two families living only blocks apart in Brooklyn’s Gowanus district. Beyond the snare of human complications inherent in such risky romance, his public role and professional reputation as a lawyer in breach of matrimonial laws escalated the danger. On top of that were his concerns about what might be going on at the law office. Some apparent practices at the fast-paced Brown, Hall & Vanderpoel firm made him fear a day of reckoning for corrupt practices might be in the offing. He’d already been swept up in something like that before, and paid a huge price despite never being a party to the wrong-doing.

The accumulating complications of his double life and the rising threat of what might happen at his embattled law firm, whose principal, Oakey Hall, was New York’s mayor and an integral part of the Tammany Hall political machine running the city and bilking its coffers, combined to produce a bold plan: Isaac Jelfs would completely disappear from the life of one family and abandon his career in New York, then reinvent himself in a new role with the other family somewhere else.

Yet, for neither “James” nor Hannah Boyer would this be the first time they found themselves starting life over in a new country.

2

On the Path of the Law

Isaac Jelfs was born May 28, 1834 (a detail “James Boyer,” with a much younger wife and also covering his tracks, would later obscure by giving 1836 as his year of birth), in Moreton-in-Marsh, an English farming centre in the northern Cotswolds west of Stratford.

Nestled along what centuries before had been a Roman roadway, Moreton-in-Marsh is aptly named, surrounded as it is by muck-rich acres. After 1227, when Moreton’s market charter was first granted, the town’s main event came every Tuesday, when the market hall and stone-cobbled thoroughfare filled with stalls of produce hauled by farmers from their fertile low-lying fields nearby.

When Isaac was a boy, a hundred-year-old tram railway ran the sixteen-mile distance between Stratford-upon-Avon and Moreton-in-Marsh, its pace gentle because the heavy freight cars were drawn by dray horses, its purpose chiefly to distribute coal that had first passed from the English coast on small sailing vessels up the Severn and Avon rivers to Stratford. On market days the railway’s tram car, fitted with a special covered top, carried passengers from Stratford out to Moreton — maids, perhaps an actor or two, buyers from the inns and taverns, fun-seeking visitors to the theatre town who’d come for evening playhouse performances — to get the farmers’ fresh produce straight from the fields that morning. A festive “market day” mood filled the Tuesday morning air and young Isaac Jelfs thrilled to it all, the dramatic highlight of his quiet week when he could enjoy action and observe strangers.

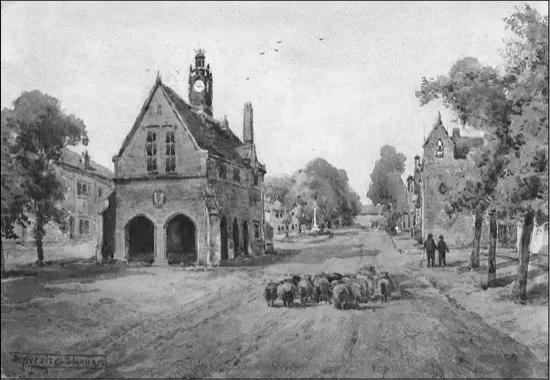

When Isaac Jelfs grew up in Moreton-in-Marsh, sheep moved unhurriedly through High Street’s market square, except on Tuesdays, the day when farmers filled the place with market-day stalls and he enjoyed the excitement.

(Watercolour print: Sylvester Stannart)

(Watercolour print: Sylvester Stannart)

Between market days, and between the two fair days in March and November each year when Cotswold games of woolsack races, shin-kicking, and the oddity of downhill cheese-rolling contests attracted lively sport and loud cheering, the town of a thousand inhabitants was serene. Sleeping cats sunned themselves in the middle of the streets, a curving array consisting of High Street where the Jelfs lived, Oxford and Church streets, Bourton and Stow lanes, Bakers Row and Back Ends, together with rear lanes and narrow burgage plots held on yearly rents. Most buildings in picturesque Moreton were warm-coloured limestone or white stucco, with thick, thatched roofs and large chimneys. The burning tang of coal smoke drifted over the town and pinched Isaac’s nostrils. Each night he heard the town bell ring out from the sixteenth-century curfew tower just along the street at the corner of Oxford, a warning reminder to townsfolk of the risk of fire at night.

Isaac knew these houses and winding streets of Moreton-in-Marsh, all little changed when his great-grandson took this photograph in 1982.

Isaac Jelfs heard the bell from Moreton’s curfew tower at right. He would still recognize these enduring buildings along his street, except for the puzzling television antennae and gas station, which appeared a century after he left the village.

(Copyright of the Francis Frith Collection)

(Copyright of the Francis Frith Collection)

Moreton was not only a market centre for farmers but a travellers’ town, too, boasting several pubs, inns, hotels, teashops, and a coaching station. From one century to the next, despite advent of the linen production central to the Jelfs’s way of life, or the shift from horse-drawn coaches to steam-engine trains when Isaac was in his teens, little else about Moreton-in-Marsh seemed to change. Lord Redesdale, for whom the market hall was named, was officially lord of the manor; however, though he occasionally held what was known as a court baron, mostly to appoint constables, effective local government here as elsewhere across England was principally in the hands of the county’s magistrate, in whose office a heavy clock ticked away the hours even as time stood still.

The Jelfs household was headed by Isaac Senior, born in 1797 at the village of Bretforton. Isaac later relocated to Moreton-in-Marsh where, in 1824, he met and married Hannah Heath. The Jelfs family was set apart from others in that it prospered neither by farming nor through the hospitality trade, but to the extent Isaac Senior wove linens and Hannah made hats. “The only manufactory here is that for linen cloth,” reported Pigot’s 1844 Gloucestershire Directory on the economy of Moreton-in-Marsh. In spinning yarn for this cloth, Pigot’s added, “some of the poorer classes are employed,” without bothering to add that such workers were poor because they could earn only a pittance in this hard-bargain economy.

Reflecting his own steady rise in the business, Isaac Senior identified himself to the census-takers in 1841 as a weaver, a decade later as a linen manufacturer. His was the same initiative displayed by other enterprising Jelfs in the region, looking to see what people needed and then supplying it. Thirty miles north in Birmingham, Isaac’s cousins likewise owned and operated small undertakings: John Jelfs was a shoemaker at 111 Holt Street; William Jelfs owned a bakery at 154 Unett Street; while James Jelfs was keeper of an eating house at 7 Lower Priory.

Ancestors of the Jelfs had migrated to England from continental Europe, most likely the Low Countries, in the late 1500s. There the name Jelfs, with various spellings, appears in records back into the thirteenth century. Although the family was Jewish, for several generations now the Jelfs had become adherents to the Church of England, the family and its descendants assimilating into English society, as such names as John, William, and James attest, although the girls still seemed to get more traditional Jewish surnames. In England, the Jelfs had morphed into Anglos in the manner of many other Jews, in order to get ahead in their new surroundings. The redoubtable British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, whose clearly Jewish name never disguised his heritage, was a leading example of this phenomenon of social integration of which the earlier Jelfs were but a part.

From the 1600s onwards in England, Jelfs families had been concentrated northwest of Moreton in the Evesham and Badsey area, living in such Worcestershire villages as Honeybourne and Bretforton, down through generations. Many Jelfs marriages embraced other ethnic and national backgrounds. Over time memories faded until family heritage became fogged over with ignorance. Contacted in connection with...