![]()

| CHAPTER 1 The World of the Aztec Scribe |

Over the span of more than three millennia before the Spanish invasions in the wake of Columbus, the American continent bore witness to the rise and fall of civilizations as diverse in character and achievement as those of the Eurasian-African landmass. A wide variety of complex societies emerged in Mesoamerica, the vast culture area stretching from the fringe of the northern Mexican desert down through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec into the Yucatán peninsula, then southwards along the trade routes of the Pacific coast as far as Costa Rica, and on to the western flanks of the Andes in South America. These cultures flourished, building the first cities of the Western Hemisphere, fostering the flowering of arts and sciences, and developing graphic communication systems that could rival those of the Eastern Hemisphere in their creativity and efficiency. The Nahuatl-speaking Mexica, or Aztecs, and the Quechua-speaking Inca are the stuff of legend because they reigned over the greatest—and last—imperial civilizations of the Americas. The still young Aztec Empire (Fig. 1.1) was not in decline but still expanding and rising to its zenith in the early 16th century, only to be destroyed willfully and wantonly by Spanish adventurers on a quest for gold and glory.

1.1. The core region of the Aztec Empire: Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco and Tlacopan to the west (at bottom), the surrounded enemy states of Huexotzinco (with Atlixco), Tliliuhquitepec, Tlaxcallan and Cholollan to the east (at the top, in typical Aztec orientation). The shield and weapons symbolize the state of ritual war between them, the xōchiyāōyōtl (see p. 41).

Mesoamerica stood out in one significant way from all other regions in the Americas: through the invention of the graphic recording, or communication, system known as writing. The origins of Mesoamerican writing are lost in the mists of time, but there is general agreement that writing is attested no later than the second half of the 1st millennium BC, and perhaps as early as 900 BC as an innovation of the Olmec civilization, the so-called mother culture of Mesoamerica, in the Isthmus area. The early Zapotec state of Taniquiecache (or Monte Albán) in Oaxaca, founded mid-millennium, and the largely contemporary Epi-Olmec city-states to the Isthmian south were the first to adopt and elaborate writing as a versatile cultural tool and political weapon.

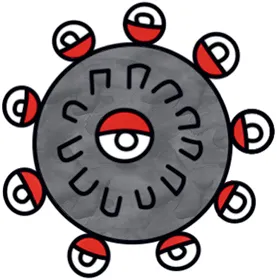

Writing, a system of language-related signs, did not develop in isolation. It was but one of three independent graphic recording systems—writing, iconography, and notation—that, when brought together, made up the complex communication system that we see in the codices (leporello-like screenfold books) of the region (Fig. 1.2). Codices are painted manuscripts on animal hide (like our parchment) or on paper fashioned from the mashed and pounded leaves of a native fig tree (amate, from Nahuatl āmatl, “paper, book”) or from the rough fiber of the maguey plant, a type of agave. Only four such codices survived the Spanish onslaught in the Maya region of southern Mesoamerica. A similar number are known from the Mixtec area of western Oaxaca, and another handful from the Puebla-Tlaxcala region to the north, which shared many of the conventions of Mixtec books and art. However, in the Valley of Mexico, the heartland of Central Mexico, none of the codices that have come down to us is an indisputable survivor of the Prehispanic period, although one in particular (Fig. 1.3), a tax record of the Aztec Empire, is an exact copy of a pre-colonial document, if not the original itself.

1.2. The Codex Fejérváry-Mayer: an Aztec screenfold book.

1.3. The Matrícula de Tributos.

Stone monuments, ceramics and murals from all parts of Mesoamerica and from all periods attest to the dominance and universal appeal of iconography, a system of concept-related symbols and symbolic representations. We see iconography even today, not only in Mesoamerica but around the globe, in the washroom icons at airports and stadia and in the crosses and crescents at houses of worship, for example, and often unaccompanied by writing. Understanding iconography does not require knowledge of the language of a particular society or societies. Only the symbols themselves and the conventions they convey need to be understood. In Mesoamerica there are very few known items of stone or other materials that bear writing but not iconography (among them are several early stone monuments from Monte Albán; Fig. 1.4).

1.4. Stelae 12 and 13, Monte Albán.

Writing is tailored to a specific language and thus in many parts of the world, even today, is often the prerogative and the tool of an elite with the time, means, and training to command it. With their specialized knowledge, scribes were typically part of that elite. By contrast, the accessible and readily acquired conventions of symbol-based communications, which were frequently of a pictorial (or iconic) nature, made iconography the domain of no single class, but of society as a whole. One need only know the narrative, conventions and associations to interpret and understand the message. A deity or other supernatural being could be readily identified by one or more characteristic elements of their clothing, or by something they hold, or by some action they are shown performing. A European parallel for this would be the representation of a saint, who can be identified by clothing (for example, Mary’s blue gown), by something held (such as Peter’s keys), by something acted out (George slaying the dragon), or even by something placed nearby (a tower for Barbara or a broken wheel for Catherine of Alexandria).

Outside the Maya area, iconography is the rule, not the exception. It is an effective medium because it is monumental in and of itself—it can be recognized and evaluated from a distance, by a diverse crowd assembling in a public area, whereas a written text is characteristically viewed close-up, and access to it can be limited by such factors as education and status. Iconography is interpreted, not read, with the help of words chosen by the beholder, whereas writing is read with words chosen by the author. In most Mesoamerican societies, including that of the Aztecs, the two systems coexist, in much the same way as illustrations and text occur together in present-day books and newspapers, sometimes in balanced symbiosis, sometimes with one medium dominant over the other, as pictures are in graphic novels.

The third medium, notation, is a system of units known variously as notes (as in music), marks (as in pottery batches), and numerals (as in calculations and tallies). It serves to differentiate, order, and enumerate, and, unlike iconography, both the sequence and placement of these units is crucial for their correct interpretation, whereas, unlike writing, notation has no rigid, linear relationship to language. Although older than writing, numerical notation frequently becomes absorbed by the latter, in which it constitutes an autonomous subsystem with its own rules and reading order. This is true of modern writing systems, in which a number such as 13 is read in non-linguistic order and not sign by sign (as “one-three,” or the like), and it is true of Mesoamerican cultures (Fig. 1.5), in which two bars (for ten) with three dots above, below, or beside them (the southern Mesoamerican tradition) or simply thirteen dots or disks (the northern Mesoamerican, including the Aztec, tradition) stand for the same.

1.5. Maya numerals in columns: zero, represented here by a red shell, and 1 to 19, represented by combinations of dots for 1 and bars for 5 (Codex Dresden, p. 44b).

As a rule, Maya monuments, like monuments worldwide, place these media side-by-side or one above the other (Fig. 1.6), with text in columns supplementing information displayed in an accompanying pictorial section (Figs 1.7a, 1.7b), which may show a scene, a symbol, or a being, such as a ruler or deity. In Mixtec (Fig. 1.8a) and Aztec manuscripts, on the other hand, iconography reigns supreme, with writing for the most part relegated to dates and to personal-name captions beside the heads, and place-name captions under the feet, of actors in a historical drama or genealogical narrative. This is similar to our practice when we annotate photos. To make it clear which names and dates relate to which persons, places and events, Aztec codices often link the name glyphs and dates to their referents by a cord, so that the name of an individual seems to float like a balloon tied loosely behind the person’s neck, and the name of a place often trails beside the referent like a tethered tag (Fig. 1.8b).

1.6. The symbiosis of graphic recording systems: writing, notation, and iconography in three successive registers of a Maya manuscript (Codex Dresden, p. 18b).

1.7. The juxtaposition of iconography and writing: a) the Egyptian ivory tablet of predynastic pharaoh Den; b) an inscription commemorating the capture of elite foes by Bahlam K’uh IV (at right), on Lintel 8 at Yaxchilan.

1.8. Juxtaposing sign, symbol and symbolic representation: a) Mixtec lords, with a calendrical name and three dates above their heads, conduct a three-day water-borne assault on an island stronghold (Codex Nuttall, p. 75); b) Cuauhtlatoa, with his name above him, defends the city of Tlatelolco, named below his feet, against a soldier from Tenochtitlan, the name glyph of which is tethered to the enemy’s foot (Codex Telleriano-Remensis, f. 33v).

It is not always easy to recognize the message in an iconographic communication. Sometimes symbols resemble glyphs in the degree of their conventionalization—the extent to which they are standardized in style, shape, size and level of abstraction. And sometimes they retain a form and size related to nature, and are integrated into scenes and portrayals as if part of the landscape and part of the depiction. In Lucas Cranach the Elder’s early 16th-century painting of the mystical marriage of Catherine of Alexandria (Fig. 1.9), we see four female saints grouped around Mary. Each saint is identifiable by a symbol that is, for the most part, indistinguishable from an object in everyday life—seated to Mary’s right is St. Catherine, holding one of her attributes, a sword, while another, a hooked wheel, lies on the ground beside her; St. Dorothy holds a basket of roses; the tower identifying St. Barbara is on a hill behind her. St. Margaret alone stands out because of the dragon resting discreetly at her feet.

1.9. The Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine, Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1516.

Precisely this kind of integration occurs frequently in Mesoamerican iconography, so the beholder must be quite alert to catch all the references. And it is important to note that there can be multiple layers of iconography, like the skins of an onion or the nested shells of a Russian matryoshka doll. In the example above, the specific symbols of the saints are nested within the broader symbolic representation of the mystical marriage as a whole. Similarly, there can be multiple layers of writing (compare, for example, in European scripts the letters c and h within the higher unit ch, each of these three with its own distinct pronunciations in context, or the semantic and phonetic units nested within a Chinese character).

The distinction between an individual symbol and a glyph is sometimes blurred. In our own society we can ask ourselves whether the characteristic yellow M logo of the McDonald’s fast-food chain is an example of writing or iconography, or a blend of both—would an M in any other typeface and color evoke the same associations? Normally, such blends are only possible, and effective, when an isolated symbol or glyph is involved, an early case in point being the famous interlocked Chi Rho monogram of the Roman emperor Constantine’s troops. From the once independe...