The structure of this book

This book is essentially concerned with the Mental Health Act 1983 as revised up to May 2019 and as it operates in England and Wales. There are some differences between the two countries in terms of the Act but more significantly with the various rules, regulations and Codes of Practice. We try to highlight the differences where they are significant. The text of the Act itself is included within this book, but occasionally readers may need to access the internet or seek other source materials for particular references (such as the Reference Guide).

The book contains some material on the Mental Capacity Act because of its relevance to mental health law. The aim is to simplify the law as far as possible to make it accessible to professionals and to those affected by the law. The main chapters give details on who operates the Act, who is affected by it, how people may be subject to compulsion, how the law governs issues of capacity and consent to treatment, how to appeal against compulsion, and the role of the nearest relative. There are chapters on advocacy, children and the importance of human rights issues. Where possible, we provide quick summaries of key points as well as grids and diagrams to help explain how the law works in practice.

The Appendices provide access to the Act itself, as well as various rules and regulations and a summary of key cases that have been decided by the courts. Appendix 8 gives guidance to transfers of patients within the British Isles.

In places we refer readers to more detailed texts on some specific areas of the law.

Why have separate mental health law?

Some authors with a civil libertarian approach (e.g. Thomas Szasz) argue that there should be no need for mental health law. Following this approach, one could argue that there might be a need for law relating to mental incapacity (e.g. for people with brain injury, dementia, learning disability), but no need for a law which allows for the detention and compulsory treatment of people just because a doctor considers them to be suffering from mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia or depression). They should be treated in the same way as anyone with a physical illness, such as diabetes.

The Mental Health Act 1959 took a more welfarist approach, accepting that it may be necessary to intervene against someone’s will where they are considered to suffer from a mental disorder, either in order to protect others, or in the interests of the patient’s own health or safety.

Even though the Government has recently been expressing a preference for using mental capacity law rather than the Mental Health Act, it resisted early attempts to include an assessment of the patient’s capacity as a key element in determining whether or not to intervene without the patient’s consent. So, with the significant exception of electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), the Mental Health Act 1983 as amended still allows for the compulsory treatment of a patient with capacity.

The Act also keeps learning disability as well as mental illness and personality disorders within its remit. This has not always been the case, as we can see from the brief historical summary which follows.

Previous law

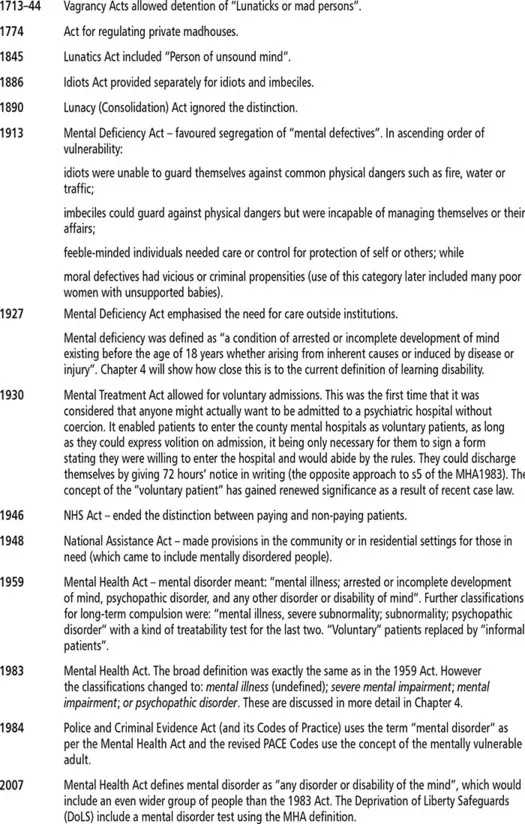

A summary of earlier law is set out below, including references to those covered by these Acts. The common law distinguished “idiots” from “lunatics” before the first of the Acts, which are listed here. These terms correspond with the distinction between people with a learning disability and those who are mentally ill. Historically, the groups have sometimes been dealt with in separate legislation and sometimes together, as in the Mental Health Act 1983. Chapter 4 will look at what now amounts to “mental disorder” in more depth.

A useful summary of the origins of mental health law in England and Wales can be found in Bowen (2007). Larry Gostin’s work for MIND (A Human Condition, volumes 1 and 2) was very influential in the lead up to the 1982 amendments that form the basis of the 1983 Act. These two short books are still well worth reading, as they provide a critical approach to mental health law (Gostin, 1975, 1977).

The lead up to the 2007 changes

The main changes brought about by the 2007 Act came into effect almost exactly ten years after the process of change began with the Expert Committee (under Professor Genevra Richardson) in October 1998. There were a number of factors which led to the reform of the 1983 Act. There had been the reduction in the number of hospital beds and a greater emphasis on care in the community, but the MHA1983 seemed primarily concerned with hospital-based treatment.

There were some high-profile cases, such as: the 1992 killing of Jonathan Zito by Christopher Clunis; the incident at the end of 1992 when Ben Silcock climbed into a lion’s den and was badly mauled; and the deaths of Megan Russell and Lin Russell at the hands of Michael Stone in 1996. The first two involved mentally ill patients in the community and the third was a man diagnosed with a severe personality disorder. There was concern that the law was not providing adequate protection to those suffering from mental disorders or to those affected by their actions.

In 1997 the “Bournewood” case started its journey through the courts. This involved HL, a man with autism and severe learning disabilities. He was admitted to hospital and kept there against the wishes of his carers. This continued for three months until a decision in the Court of Appeal led to his detention under the MHA1983. During this period he was effectively detained in hospital, but without any of the procedures or protections of the MHA1983. This case is dealt with in more detail in Chapter 11 as the issues it raised have been highly influential in reforming the law, especially those parts of the MHA2007 which reform the MCA.

In 1998 the Human Rights Act was passed and eventually came into effect in 2000. The Government was concerned that mental health legislation should be reformed to be consistent with the requirements of this new Act, which enshrined most of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) within English law. One example involved the relationship between the patient and the nearest relative. In JT v United Kingdom (2000) the Government agreed that the Mental Health Act needed reform so that the patient could have some say in who should act as the nearest relative.

The Richardson report was published in 1999 at the same time as the Government published a Green Paper on Reform of the Mental Health Act. One of the main differences between the two approaches was the Expert Committee’s recommendations that assessments of mental capacity should play an important part in mental health law. The Green Paper did not take this approach, nor did it support the Richardson proposal of reciprocity where any use of compulsion should be linked to a duty to provide appropriate services. These two reports were followed by a White Paper, which was published in 2000. After a period of consultation we saw the first draft Bill in 2002.

The draft Mental Health Bill was met with fierce criticism from a number of quarters. Issues raised at this stage have continued to be contentious. The definition of mental disorder was seen by many as being too wide and there was concern that this would lower the threshold of compulsion. There also seemed to be a lack of emphasis on therapeutic purpose, with the disappearance of the treatability test and a greater focus on public safety. The proposal that the Mental Health Review Tribunal should have a much greater involvement (including being the body that, in effect, would need to approve long-term compulsion) was seen as cumbersome and impractical.

The Mental Health Alliance was formed to coordinate the views of many of the protesting parties. There was a protest march in London in September 2002, which highlighted concerns about the proposed changes, in particular the community treatment order with the prospect of forcible medical treatment in the community. The Government, however, was determined to introduce some kind of new compulsory treatment provision in the community.

Running alongside the reform of the Mental Health Act was the Government’s concern with dangerous people with severe personality disorders (DSPD). This was linked with concerns about cases such as Michael Stone. The Government believed that the definition of mental disorder was too tight and, combined with the treatability test, was preventing some dangerous individuals from being detained in hospital. At one point, separate legislation was considered but eventually the aims of this Home Office-driven approach were subsumed within the amendments to the MHA1983. Some changes in the Act are hard to understand without an awareness of this DSPD agenda.

A second draft Mental Health Bill was produced in 2004. This was examined by a Joint Parliamentary Committee, which reported in 2005. The report recognised the need for reform but considered the Bill to be too long, too complex and too concerned with public safety at the expense of patients’ rights. In 2004 the European Court of Human Rights determined that HL (the Bournewood patient) had been detained under common law and that the lack of any formal procedure or recourse to review had breached Article 5 of the ECHR. This important decision needed to be reflected in the revisions to the MHA1983 and a consultation paper on this aspect of the law was produced in 2005.

While this rather convoluted process continued, the amending of mental health law was overtaken by the Mental Capacity Act, which was passed in 2005. This has had an increasingly significant impact on the use of the Mental Health Act, as we shall see later in the book. The Mental Capacity Act is summarised in Chapter 9 and considered in more detail in a companion volume (Brown et al., 2009).

Then in 2006 the Government announced the demise of the second draft Bill. A further Bill was produced which would amend the 1983 Act rather than replace it. This received Royal Assent in July 2007 as the Mental Health Act 2007. In the final stages (known as “ping-ponging” between the House of Commons and the House of Lords), the Lords wrung a number of concessions from the Government which are of some significance. Ten years of work had culminated in what amounts to a comparatively minor amendment Act, most of which came into effect in November 2008. History may regard this as a wasted opportunity.

The main changes

As stated above the MHA2007 was an amendment Act rather than a radical overhaul of mental health law. The main changes are summarised below. Key issues arising from the changes are highlighted. Each of them is dealt with in more detail later in the book.

The definition of “mental disorder” was broadened with limited exclusions. The definition is: “any disorder or disability of the mind”. The specific classifications of mental illness, severe mental impairment, mental impairment and psychopathic disorder all disappeared. Promiscuity, other immoral conduct and sexual deviancy were no longer to be exclusions. Previously, by themselves, they were not to be seen as mental disorders. The only remaining exclusion was to be dependence on alcohol or drugs. Li...