eBook - ePub

Redefining Irishness in a Coastal Maine City, 1770–1870

Bridget's Belfast

Kay Retzlaff

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 222 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Redefining Irishness in a Coastal Maine City, 1770–1870

Bridget's Belfast

Kay Retzlaff

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Redefining Irishness in a Coastal Maine City, 1770–1870: Bridget's Belfast examines how Irish immigrants shaped and reshaped their identity in a rural New England community. Forty percent of Irish immigrants to the United States settled in rural areas. Achieving success beyond large urban centers required distinctive ways of performing Irishness. Class, status, and gender were more significant than ethnicity. Close reading of diaries, newspapers, local histories, and public papers allows for nuanced understanding of immigrant lives amid stereotype and the nineteenth century evolution of a Scotch-Irish identity.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Redefining Irishness in a Coastal Maine City, 1770–1870 è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Redefining Irishness in a Coastal Maine City, 1770–1870 di Kay Retzlaff in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Historia e Historia moderna temprana. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 Irish in Public

DOI: 10.4324/9781003187660-1

The next murderous assault which we have to record was committed upon one Bridget McCabe, an Irish woman, who died from the effects of wounds given by persons unknown, during a disturbance at the house of her husband, Brian McCabe, on the 4th of January, 1861. A coroner’s inquest failed to discover the guilty party.1

Four January 1861, Belfast, Maine. It was snowing—again. Bad weather arrived Christmas week and stayed: it snowed, rained, and sleeted on 20, 22, 24, 25, and 26 December. After a couple days’ respite, the snow began again during the night of 30 December, dumping eighteen inches on the small city on the western shore of Penobscot Bay by noon the next day.2

The New Year’s Eve storm was an omen. January 1861 proved to be miserable—Belfast got more than forty-four inches of snow before month’s end—it snowed sixteen out of thirty-one days. The temperature dropped to nearly ten degrees below zero on the thirteenth. The average temperature was seven degrees colder than the previous year. It started snowing again around 3 p.m. on 4 January 1861.3

One person, however, was beyond caring.

Twenty-six-year-old Bridget Haugh McCabe took a couple of days to die during that first week in January in a dilapidated house down in Puddle Dock near harborside. No one intervened, even though people passing by heard “violent language” over the course of several days.4 It was, after all, a house known to be home to a bunch of wild Irish; it was also a matter between husband and wife. The public consensus was that the screaming was the result of a drunken brawl. McCabe had been a Belfast resident for at least eight years—she married Brian McCabe in 1853. When she arrived is impossible to glean from public records, although her father, Thomas Haugh, is listed in the 1850 census.

Details of Bridget Haugh McCabe’s death on 4 January 1861 emerged through two weekly newspapers, The Republican Journal and The Progressive Age. Miles Staples, coroner, gave at least two possible causes of death—either Bridget’s left arm had been submerged in scalding water, or she had suffered from “erysipelatous inflamation [sic]” caused by an injury to the arm.5 At the time of death, gangrene had set in. Because no one had summoned a doctor, Staples declared, no one could say for certain what had happened—although he and the jurors had strong opinions about who was guilty:

The jurors cannot conclude their verdict without, in the most unqualified terms condemning the studied and apparently concerted disposition on the part of the principle witnesses, including that of the father and husband.6Rum, beastly drunkenness, nightly rows, imprecations, outeries [cq] of murder, with the most abandoned brutality of conduct, witnessed and heard by good citizens, with from four to five misterious [sic] deaths of Irish persons, who were last seen in or about the premises of one individual and in two instances the wives of that individual; has justly caused this community to feel indignant and demand a full investigation by the jurors.7

Staples concluded that Bridget died when the inflammation reached her brain.8

This mention of “Irish persons” in the newspaper is one of the few public acknowledgments that there were Irish immigrants living in Belfast, Maine. Joseph Williamson, author of a two-volume history of Belfast, rarely discussed that community. He did, however, spend several pages explaining how the “Scotch-Irish” were mistaken for Irish, took time to talk about the patriotism of the non-Irish settlers who had emigrated from Ulster, and discussed the non-Irish settlement of Belfast in detail. While Williamson, an amateur historian, did not write about the Irish community, as judge of Belfast’s police court in the 1850s he came into constant contact with members of that community who ran afoul of mainstream Belfast society.

In one instance Williamson overcame this limited viewpoint—he devoted several pages of his history to discuss William Brannagan, an immigrant from County Meath, who made enough money to pay for the construction of a Catholic church in Belfast, Saint Francis of Assisi.9

Brannagan arrived in Belfast in 1841 via mercantile channels, having first immigrated to Philadelphia, where he worked as a gardener. Within a few years of his arrival in Belfast, Brannagan was thoroughly integrated into its young men’s groups, being one of the founding members of a temperance society.10 He opened his own dry-goods and boot-and-shoe business in downtown Belfast.11 After a few years, he sold out and became a salesman for others for the next thirty years. He never married, managed his money wisely, and remained firmly entrenched in Belfast’s economic life.

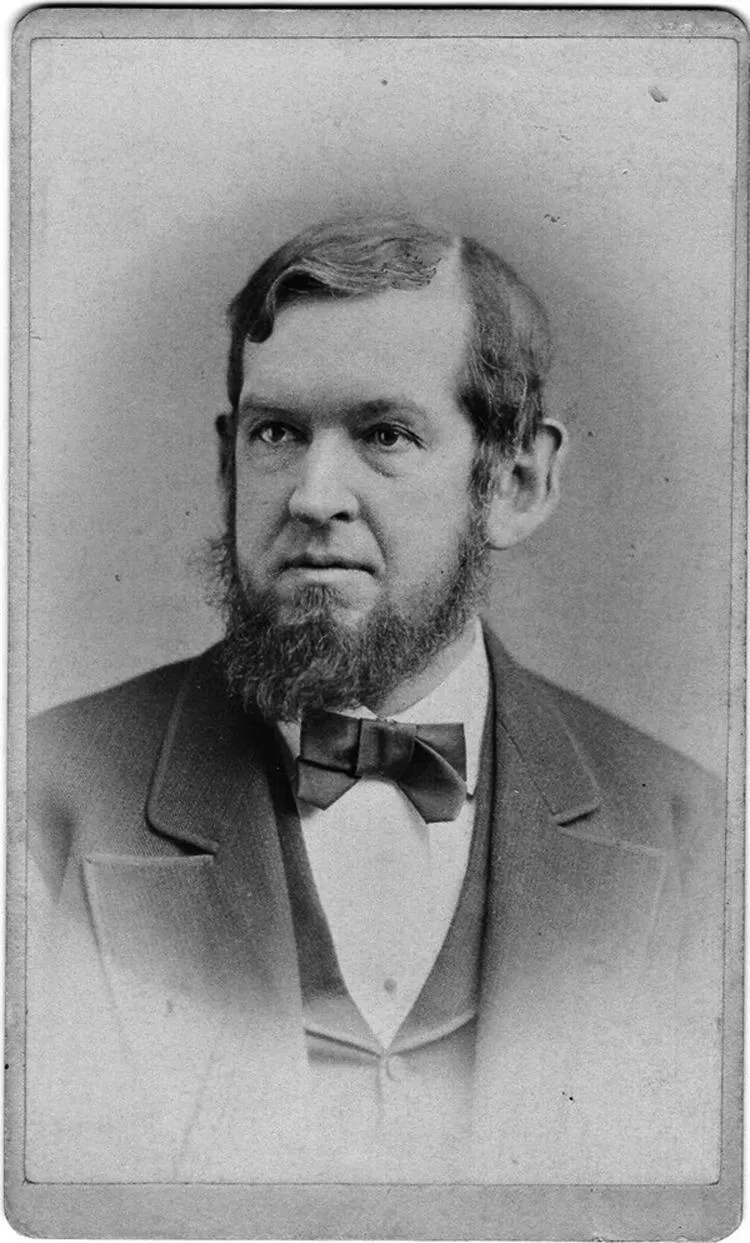

Figure 1.1 Joseph Williamson Jr., amateur historian and lawyer. Courtesy of the Belfast Historical Society and Museum.

Bridget Haugh McCabe and William Brannigan may well have passed each other on Belfast’s streets in the 1850s. And they were most certainly identified as Irish in their public gestures, behavior, and actions. Their stories, however, suggest that a spectrum of impressions and reactions, tinted by gender- and class-based understandings, combined to affect their public lives in this small community.

When Williamson included Bridget Haugh McCabe in his history, he did not present her as a woman, an individual, but as a victim of Irish violence. To be fair, no women, even those of higher social status, garnered a biography in Williamson’s histories. He included Bridget’s death story in a chronology of serious crimes committed in or brought to trial in Belfast. In Williamson’s telling, McCabe was one of four women killed (or severely wounded) by men they knew.12 Generally, women only earned mention in Williamson’s necrology section.13 And, as women were supposedly not involved in business, they were not deemed worthy of note. Williamson, however, seems to have intentionally overlooked the fact that a number of women he knew were involved in the business life of Belfast. After his wife died, for example, he boarded in the Field House, which was run by wives of elite Belfast males.

If not for Bridget’s mysterious death, probably very few people in 1861 Belfast would have heard of Bridget Haugh McCabe. Irish immigrants made up less than 5 percent of Belfast’s population. Bridget wasn’t yet thirty, married to a man sixteen years her senior, and but was mother of three children, all under the age of six. She was also stepmother to Charles Spinks, fifteen years old, and William A. McCabe, ten, still at home, the sons of Brian McCabe’s previous wife, Mrs. Margaret Spinks McCabe, a widow, who had married Brian McCabe in 1849.14

There are no death records for Margaret Spinks McCabe; yet just four years after their marriage, Brian McCabe married sixteen-year-old Bridget Haugh in 1853. As the coroner hinted, Brian McCabe was somehow implicated in Spinks’ demise as well. Because Bridget was illiterate, the only written records of her existence have been left as a result of her interactions with the larger Belfast community. Her marriage to Brian McCabe is listed in city vital statistics. The U.S. census materials record her children’s names and ages. Her death was noted in the city’s vital statistics, as well as court records, and, of course, the two local weekly newspapers both ran articles on the event. She was not afforded the same deference other women in the community were given—even in death.

Figure 1.2 Surviving Puddle Dock house, still in use in the twentieth century. Courtesy of the Belfast Historical Society and Museum.

Bridget’s death under mysterious circumstances on 4 January 1861 in the Puddle Dock area of Belfast, Maine, was the hot topic in town. Although her death garnered only about twenty column inches in the local newspapers, within that short space she was verbally stripped naked and her corpse displayed for the titillation of the paper’s readers. What else remained to be said? The first written report of her death came a week after the fact, published in The Progressive Age:

SUDDEN DEATH—SUSPICION OF FOUL PLAY—There was quite a sensation in this city on Saturday from the report of the sudden death of a woman named Bridget McCabe, wife of Bryan McCabe, which took place early in the morning of that day, and that she came to her death from blows inflicted by her husband or some other person.15

The story ran on page three—the one reserved for local stories—pages one and two being consumed by goings-on in Washington, D.C., and the unraveling political world in the weeks before Fort Sumter was fired upon by Confederate troops. The Progressive Age played up the sensational nature of her death. Half way through the first paragraph, the paper reported: “From the facts testified to, it seems that the body was found in bed in the morning entirely naked except a coverlit [sic] thrown over it.” The paper went on to give a great deal of information garnered from the coroner’s report, to whit:

one of the arms from the shoulder to the wrist was much discolored as if from bruises; from the wrist, the flesh was entirely denuded of skin, the finger nails coming off with the skin and the flesh of the inside of the hand peeling off from the bones. Up and down the back the flesh was much discolored appearing as though mortification had taken place.16

The coroner, Miles Staples, noted that gangrene had commenced. Bridget, he determined, had died of infection of the brain. He also determined that she had been injured on Wednesday night, 2 January 1861, as a result of a drunken row.

The Republican Journal, the other Belfast weekly, quoted the coroner’s report, including the accusation that Brian McCabe had had a nefarious hand in the deaths of his two wives.17 It was thus only at the inquest into Bridget’s death that the host community discussed in public documents the situation in Puddle Dock and speculated as to what had happened, not only this time, but in the recent past. It was at this juncture that the first Mrs. McCabe, Margaret Spinks, reentered the picture. Evidently, rumors had been afoot in Belfast that McCabe murdered his first wife. No such evidence exists—if it ever did. There is nothing in the Vital Records or the newspapers. There is no grave marker in any local cemeteries. Margaret Spinks McCabe simply disappeared, leaving behind four children and a widower. She left as quietly as she came into the public sphere.

Bridget’s passing was not quiet. The public noticed that something untoward was afoot, yet, even though there had been screams over the course of several days before her death, no one in the host community intervened, no one checked to see the cause of the commotion, no one became involved. Closed doors evidently made the affair a private matter—something between husband and wife. But such was not always the case in Belfast.

Changing Mores

In 1829, a man named Hamilton was known as a wife beater, which raised hackles as well as eyebrows in Belfast, when “the shrieks of the poor woman gave notice … that...