![]()

Chapter One

Prefabrication – Definitions and Explanations

Origins and Early Applications

Nomadic Tent Architecture

Early nomads were among the first engineers and users of prefabrication that we would recognize today. We associate nomadism as a lifestyle of moving from one place to another, suggesting an attentiveness to portability and all the inconveniences associated with such a way of life if compared to life within a settlement. Whilst they were not equipped with the benefits of an industrialized off-site manufacturing (OSM) process that we would recognize today, the solution available for them to provide their mobile home was nonetheless facilitated by a simple kit of parts; namely, a timber-framed structure covered with a patchwork of skins. The assembly process associated with the early nomadic tent was, by and large, similar throughout various regions, although the circular ‘plan form’ layout and size might have varied within different nomadic cultures and would have evolved further throughout the centuries, even up to the present times. The circular plan form of the ger is a natural and obvious choice in exposed locations for the Mongolian nomads of Central Asia as the circular structure has less resistance to wind. Wind and water move naturally around a circular building with greater ease than compared to a square-cornered structure, and our present-day obsession to manage air tightness and water ingress remains omnipresent. Similarly, a rounded roof will facilitate further by preventing ‘air-planing’ in strong wind conditions which can cause the roof to be torn off a building.

The essence of the traditional Mongolian ger, meaning home, or yurt in Turkish, extols the epitome of simplicity. They consist of expandable timber lattice wall sections which, when opened up to a given height, form a circular plan arrangement when connected together. Straight timber poles (rafters) form the roof which connects the circular crown to the top of the circular lattice wall structure. The crown, or tono, is a special piece of craftsmanship, often handed down from one generation to the next; it forms a central tie at the top of the structure and at the same time, creates a nucleus within the space where the fire for cooking is located, allowing smoke to dispel at high level. This simple building concept is applied even today in recreational enterprises that are located in natural environments deemed to be particularly sensitive, such as forests, ski-huts, wellness and retreat centres and lodge sites. As such they are not considered to be a formation of a built environment as we would describe them in today’s context, primarily because these structures are not permanent and can be removed within hours.

Traditional Mongolian ger (‘yurt’ in Turkish).

The tono, central piece that forms the nucleus of the family’s ger.

For early nomads, mobility remained a prerequisite for exploiting food resources that relied upon tending their livestock at various locations at different times and climatic conditions during the year. Such a way of life dictated the necessity for creating a shelter from the elements and, in some instances, doing this in very severe climatic conditions, varying from extremely cold to excessively hot. One common feature for nomads living a life on the move necessitated the capacity for them to be able to move camp from one location to another as circumstances dictated and this is reflected in the ease with which they were able to pack up their temporary home and move. It is understood this operation could be completed within the daylight hours of the shortest day, facilitated mainly by the simplistic methods of disassembly and erection with materials specifically employed for the purpose and it is this distinct feature of nomadic life which differentiates them from the settled peoples. Modern-day nomads have the ability to dismantle the ger, pack up their entire building and load it onto a small truck within four hours, such is the level of sophistication associated with their prefabricated homes. The earliest form of prefabricated building, therefore, had its origins in architecture on the hoof but in more current times it is from the rear of a small truck, where flexibility and portability, together with ease of assembly, remain and form the prerequisites for the chosen lifestyle.

Mongolian ger under assembly.

For the UK, history directs us to the earliest contribution of formalized prefabrication to the period of Britain’s colonization when, in the mid-sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the impetus to establish settlements was uppermost in locations like Australia, New Zealand, North America, India and so on. R.E. Smith (2010) refers to timber-framed components for housing being manufactured in Britain and shipped to various locations. It would be reasonable to suggest that for the users of the early nomadic tent or the British settlers’ timber-panelled house, their relationship with the new environment within which they were sited was not identified in the context of architectural principles or planning rules but more for the structure to perform the function for which it was intended.

Manning’s Portable Cottage

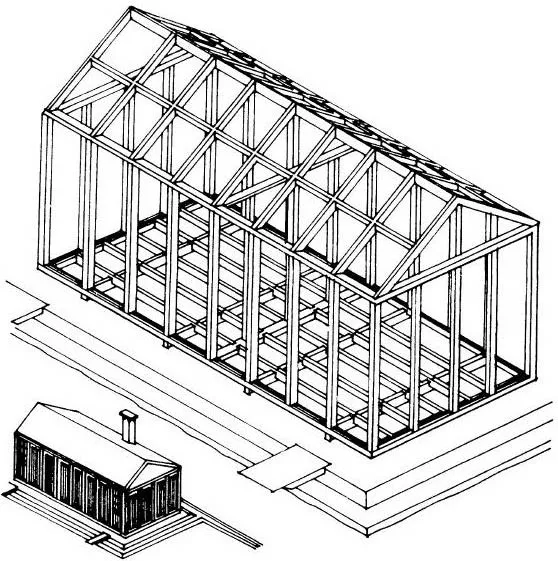

John Manning, a London carpenter and builder, had a clear and simple vision for providing immediate accommodation for his son landing in Australia in 1830. He was perhaps the pioneer in prefabrication as we might identify with today, although this was not obvious to the building industry at the time. Later known as the Manning Portable Colonial Cottage for Emigrants, the house was an expert system of prefabricated timber frame and infill components (Smith, R.E., 2010).

Manning’s Portable Colonial Cottage for Emigrants.

Simple timber panels were easily assembled within his workshop and, when secured together, provided the means with which to create a basic building structure and enclosure in one exercise. Here the wall panels were employed to perform the structure as well as the infill, very much akin to the conventional practice with masonry structure, except that for Manning the structural wall panels were manufactured off-site and transported to the site (the colonies) for assembly. This very simple concept, synonymous with the principles of mass production, is representative of the first step into standardization and prefabrication practice. It paved the way for many more developments of standardization and prefabrication, not only in timber but also in concrete and steel later. For the ever-expanding British Empire of the 1800s which promoted settler expansion to the far reaches of its colonies, the concept of standardized prefabricated components was vital. It allowed for wall and roof panels to be shipped with the new settlers, thereby providing an instant housing solution without depending on the local natural environment for their building materials and supplies which, in some locations, might not even have existed. In many respects the concept is not too dissimilar to present-day practice where timber panels as a panelized or volumetric system are produced within a factory environment and transported to the site location where panels are incorporated into a conventional building process, or where modular units are assembled to create a modular building and, in some instances, shipped overseas but in the opposite direction to the transactions of the 1800s.

The concept that lies behind full standardization and prefabrication, epitomized by Manning’s cottage design, was not really understood or exploited with the advances of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, the manufacturing industrialist had more of a focus on an opportunity to manufacture ‘parts’ for a building at worst and ‘building systems’ at best. The thrust that lay behind the very early development of prefabrication was left mostly to the industrialist who naturally focused on producing buildings in the most cost-effective manner. Due to the absence of specific or meaningful architectural design expertise at the critical stage of its development, standardized prefabrication became a much despised approach within the built environment, as many of its effects are recalled by those of the Eastern Bloc countries in Europe and in the UK also. Manufacturing industrialists, however, were certainly alert to the opportunities and occupied the design void to best accommodate their investment on their own terms. The modularity that evolved at that time was more, by default, led by construction systems and assembly techniques originating from within the factory environment as opposed to being driven by architectural design. Consequently, solving the social problems of that time was led by building/construction applications, as opposed to architectural design solutions, where social need formed the principal ingredient as opposed to a desire for aesthetic quality. Architects and designers failed somewhat to recognize the potential of joining up architectural design with manufacturing and assembly processes.

Whilst the UK was already exporting prefabricated ‘flat-pack’ houses to the colonies around the 1800s the epitome of construction systems and prefabrication arrived in a more formal sense with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. This let loose a myriad of building systems and concepts surrounding standardization based on disciplined geometry where new manufacturing processes introduced standardized iron components. Standardization and prefabrication technology continued to be explored as a means for enhancing construction practice, but insufficient design expertise was employed (and by architects especially) to render the enterprise more viable aesthetically. Joseph Paxton, more a gardener than an architect, was instrumental in introducing some fresh design principles and particularly in relation to prefabrication. He identified a perfect solution whereby he satisfied his design brief by fulfilling a building’s commercial obligations in parallel with delivering aesthetically as a natural process.

From Hand-Built to Factory-Made

Here we use ‘construction’ as being the construction processes relating to the built environment (the built environment being the entity for architecture) as opposed to construction processes that might apply to the building of aircraft, motor cars, telephone apparatus or similar complex items.

In order to understand what is meant by conventional forms of construction we need to appreciate firstly the characteristics that make up its ingredients. The term ‘traditional’ would suggest a method of construction employed over many generations which has become the conventional technique for construction dictated essentially by global location and materials available within that given place. For instance, a stone cottage in Wales is synonymous with this environment due to the abundance of natural stone that is easily quarried, just as a timber log cabin relates to the surroundings found in certain parts of America or within the Scandinavian countries, for example. Indeed, there remain numerous examples of traditional timber houses in the city of Vilnius in Lithuania where these historic buildings are still inhabited but nonetheless are located on the very edge of the commercial centre’s more modern architecture.

Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851 highlights an early transition from the more hand-built construction practice to components manufactured in a factory and dispatched to the site for assembly. The Crystal Palace also highlighted a direction in prefabrication as the design brief set by the Building Committee, which included renowned engineers such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Robert Stephenson, who specified particular design requirements for a building to demonstrate to the world the status of British industry. By 15 March 1850 designers were invited to prepare and submit their design proposals. Fundamental to their submissions was that their designs had to deliver a building that must be temporary and that it had to be as simple and as economical as possible. Additionally, the building had to be economical to build and completed within the shortest possible time available prior to the grand opening scheduled for 1 May 1851. Architects submitting their designs for this competition were perhaps generally content to follow the aspirations and objectives of their existing aristocratic patrons and clients, but by 1850 Britain was in a new place socially and commercially.

Paxton showed interest in the project following the Building Committee’s rejection of all 245 initial entries. His design represented an excellent interpretation of prefabricated architecture and satisfied the design brief wherein the 10in × 49in size of the glass panes was dictated by the ability of the glass supplier. The cast-iron columns and girders, too, were manufactured within a factory and brought to the site for installation. Paxton’s design demonstrated a clarity in standardization and modularity where the structural iron grid functioned in harmony with the capacity of the glass panels. Paxton’s prefabricated Crystal Palace, then, is a purist vision of prefabricated architecture where factory manufacturing and assembly processes followed a design concept for the building in a purposeful and meaningful manner representing a beauty in its own right.

The dual concept of prefabrication and standardization expresses the attributes of the Industrial Revolution but not all of this form of enterprise provided the built environment with the most satisfactory design aesthetic. Expressions like ‘unitized building’ and ‘building with systems’ did not always convey a positive association with prefabrication and standardization. Indeed, there is evidence which prevails in the countless examples of prefabricated slab constructions within Eastern Europe (Staib et al., 2008) which provides credible reason for prefabricated architecture to be a totally bespoke design specialism only and for prefabrication to do its own thing under the auspices of manufacturing or as an aspect of the construction process (Knapp, 2013).

Prefabrication is not new; it has been with us for many centuries in one form or another, either totally made or aided to some degree through manufacturing and assembly processes. Within the last twenty years, especially with a leap forward in technology and manufacturing possibilities, prefabrication has presented itself as a viable alternative to conventional building methodologies. It is sometimes seen as a panacea for delivering buildings which might not otherwise be possible through conventional practices where the focus is on more building for less cost. Where negative perceptions surrounding prefabrication continue to exist in the current context, they tend to have remained as a mindset resulting from examples of poor design or poor construction or both. This is supported perhaps by the lack of any meaningful evidence to demonstrate that architects were engaged in the early manufacturing processes as part of the architectural design process. A common topic surrounding the prefabrication architecture debate is the absence of commitment from procurement officials to large-volume projects in order to make it sensible and financially viable for off-site manufacturers to engage totally and for architects to adopt a committed holistic approach to design where manufacturing and assembly process are integral to the building’s prefabricated architectural design solution. Joseph Paxton, the gardener, was able to demonstrate over one hundred and fift...