The SAGE Guide to Writing in Corrections

Steven Hougland, Jennifer M. Allen

- 160 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

The SAGE Guide to Writing in Corrections

Steven Hougland, Jennifer M. Allen

Informazioni sul libro

As part of the SAGE Guide to Writing series, The SAGE Guide to Writing in Corrections, 1e, by Steven Hougland and Jennifer Allen, focuses on teaching students how to write in the academic setting while introducing them to a number of other professional writings specific to the correctional profession, such as the pre-sentence investigation report, contact sheets, court status reports, incident reports, rehabilitation and therapy. Covering correctional institutions as well as community corrections, the goal is to interweave professional and technical writing, academic writing, and information literacy, with the result being a stronger, more confident report writer and student in corrections. This text will be a concise supplemental writing book in courses focused on writing in the criminal justice discipline, report writing, or in introductory corrections courses.It is part of a series of books on this topic that will span criminal justice, policing, corrections, and research methods.

Domande frequenti

Informazioni

Chapter 1 The Basics of Writing

Basic Grammar Rules

The Sentence

The Subject

- The victim reported the crime. Who reported the crime? The victim.

- I responded to the scene.

- I arrested the defendant.

- The Corrections Officer read the inmate his Miranda rights.

- The inmate entered the cell.

- “Stop!” The subject is not clearly stated, but it is implied or understood to be “you.”

- “Sit down!”

- “Halt!”

The Verb

- The Corrections Officer drove. Drove tells what action the subject (Corrections Officer) did.

- The Corrections Officer was dispatched to Pod C. Was dispatched tells what action is taking place.

- I restrained the inmate.

- Stop! Remember the subject in a command is the implied “you.”

- I did not respond to the call.

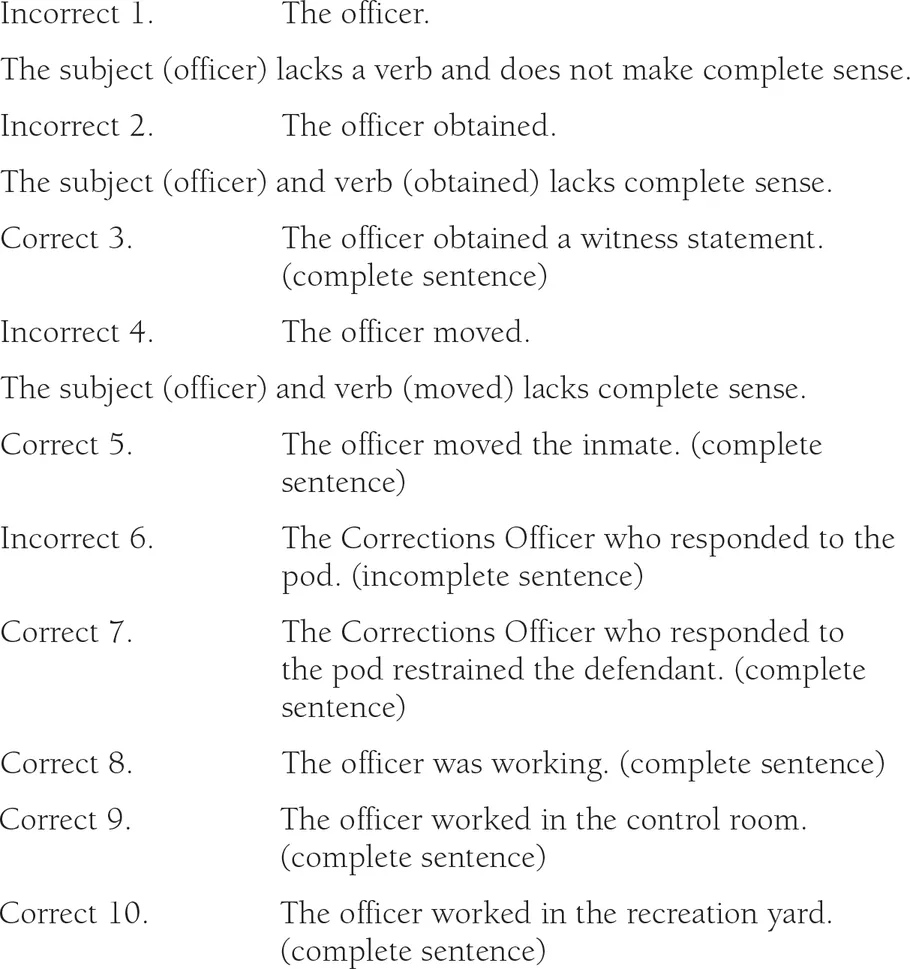

Standing Alone and Making Complete Sense

Exercise 1.1

- I (subject) + arrested (verb).

- The inmate entered the victim’s cell.

- The inmate smashed the victim’s radio.

- He removed a canteen card from the cell.

- The stereo is valued at $300.00.

- I processed the scene for evidence.

- The inmate punched the victim in the face.

- The inmate removed the victim’s property from the cell.

- I responded to the scene.

- I moved the inmate.

- I transported the defendant to Central Booking for processing.

Structural Errors

Fragments

- Entered the cell. (no subject)

- Processed the scene. (no subject)

- I the scene. (no verb)

- At the scene. (no subject or verb)

- I processed. (lacks completeness)

Run-On Sentences

- Example 1: We arrived at the scene Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

- Sentence 1: We arrived at the scene.

- Sentence 2: Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

- Revision Strategy 1. Create two independent sentences.

- Revision 1. We arrived at the scene. Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

- Revision Strategy 2. Join the independent clauses with a comma and a coordinating conjunction such as and, but, for, nor, or, so, or yet.

- Revision 2. We arrived at the scene, and Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

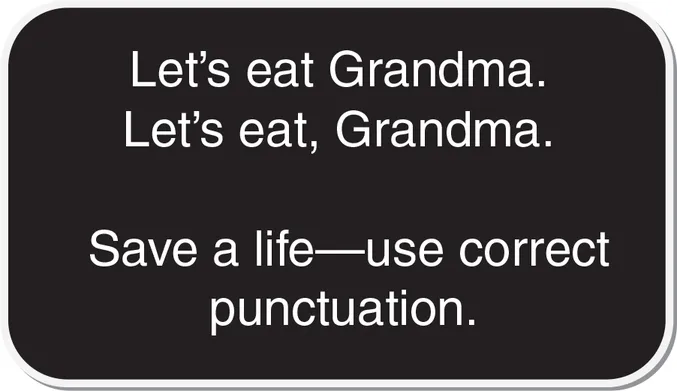

- Punctuation Alert! Always place the comma before the coordinating conjunction.

- Revision Strategy 3. Join the independent clauses with a semicolon if they are closely related ideas.

- Revision 3. We arrived at the scene; Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

Comma Splices

- Example 1. We arrived at the scene, Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

- Revision Strategy 1. Separate the two sentences by adding a comma followed by a coordinating conjunction Corrections Officer.

- Revision 1. We arrived at the scene, and Corrections Officer Smith interviewed the victim.

Punctuation

Commas

- I arrested the defendant, and I booked him into the jail. Two independent clauses:

- I arrested the defendant.

- I booked him into the jail.

A comma is required before the coordinating conjunction. - I arrested the defendant and booked him into the jail. One independent clause: I arrested the defendant.One dependent clause: booked him into the jail. (no subject)A comma is not used.

- I interviewed the victim, and she gave a sworn statement.

- I interviewed the victim, but she refused to give a sworn statement.

- Deputies Smith, Jones, and White responded to the call. (correct)

- Deputies Smith, Jones and White responded to the call. (incorrect)