- 320 pagine

- Italian

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

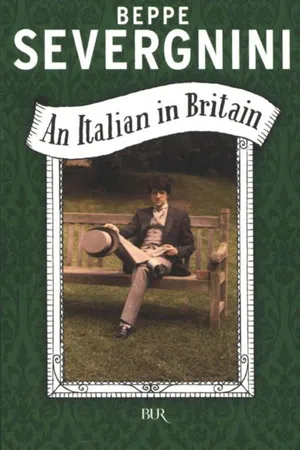

An Italian in Britain

Informazioni su questo libro

England and the English deserve to be examine in depth and Mr Servegnini goes on to explore this mysterious island with irony and verve. He describes how English dress, what they eat, how much they drink, and why they are so obsessed with a certain kind of wallpaper. It may not be a tourist guide but any tourist will find all kinds of suggestions, explanations and information about the country.

Domande frequenti

Sì, puoi annullare l'abbonamento in qualsiasi momento dalla sezione Abbonamento nelle impostazioni del tuo account sul sito web di Perlego. L'abbonamento rimarrà attivo fino alla fine del periodo di fatturazione in corso. Scopri come annullare l'abbonamento.

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego offre due piani: Base e Completo

- Base è ideale per studenti e professionisti che amano esplorare un’ampia varietà di argomenti. Accedi alla Biblioteca Base con oltre 800.000 titoli affidabili e best-seller in business, crescita personale e discipline umanistiche. Include tempo di lettura illimitato e voce Read Aloud standard.

- Completo: Perfetto per studenti avanzati e ricercatori che necessitano di accesso completo e senza restrizioni. Sblocca oltre 1,4 milioni di libri in centinaia di argomenti, inclusi titoli accademici e specializzati. Il piano Completo include anche funzionalità avanzate come Premium Read Aloud e Research Assistant.

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Sì! Puoi usare l’app Perlego sia su dispositivi iOS che Android per leggere in qualsiasi momento, in qualsiasi luogo — anche offline. Perfetta per i tragitti o quando sei in movimento.

Nota che non possiamo supportare dispositivi con iOS 13 o Android 7 o versioni precedenti. Scopri di più sull’utilizzo dell’app.

Nota che non possiamo supportare dispositivi con iOS 13 o Android 7 o versioni precedenti. Scopri di più sull’utilizzo dell’app.

Sì, puoi accedere a An Italian in Britain di Beppe Severgnini in formato PDF e/o ePub. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Print ISBN

9788817100434eBook ISBN

9788858632215FOREWORD

I couldn’t touch An Italian in Britain. It was my first book and I am fond of it. I wrote it between 1988 and 1989, and it was published by Rizzoli in 1990. It was brought up to date only once, in 1992, after the Hodder & Stoughton edition of the previous year, which carried the original title (Inglesi), and – much to my surprise – became a bestseller in Britain. In Italy, the book has been reprinted twenty-five times. Now it has been re-translated by Kerry Milis, an American who lived in Britain for many years, to whom I am very grateful.

An Italian in Britain describes the country of Margaret Thatcher as it tried to shake itself out of its post-imperial lethargy. Several years on, I am pleased to see that I sensed its underlying strength - in those days everyone talked about "the British disease" – and predicted a brilliant future (I shouldn’t boast but how often does a writer get to say he was right?).

Since my book came out, I’ve gone back to Britain often. I continue to hang out in Notting Hill and the Reform Club, I occasionally appear on TV and speak on the radio, and I can get any dinner party going by bringing up European monetary union. In 1993, while doing a stint at The Economist in London (I’ve been their Italian correspondent since 1996), I was able to move back into my former house in Kensington. Recently, I went back to London for a short stay and wrote a few more pages about the city. The British still fascinate me, even when I find them hard to understand. I can’t tear myself away from them and wouldn’t want to.

I have continued to write about them, too. So I thought I might put together a few of these pieces to explain what has changed (Blair has come and Diana has gone, Spice Girls marry football players, the class system is finally showing cracks and in London you eat a lot better). I divided my postscript into two parts. In part one, I offer some thoughts about the "new British", taken mostly from Corriere della Sera and The Economist. In part two, I have compiled five descriptions of London (from 1993 to 2003) that I hope you will find useful on a visit.

As for everything else – for the eternal Britain, the one that will discover the bidet around 2220 (maybe) – I refer you to the original text. Certain British things fortunately never change.

PREFACE

dp n="10" folio="10" ? dp n="11" folio="11" ?Beppe Severgnini was a young man not much over twenty scribbling away for a small Crema newspaper when a mutual friend brought him to my attention. I read his pieces and liked them so I phoned their author who was studying for a notary’s exam at the time and signed him up at Il Giornale. After a few months of work, he came to me to say he was going back home to resume his studies. A few months later he asked me to take him back. I did, and to get him out of temptation’s way, I sent him off to be the London correspondent. I received a lot of criticism for the decision, some of it warranted: to be a correspondent, especially in a capital city like London, you needed experience and Severgnini had none. But I spotted his natural talent and won the argument. Even before he understood the language, the little provincial Severgnini understood the country, its grandeur, its misery, its quirks and vices.

Severgnini, stayed in England for four years, and this book is one result. I want to say right away that this is not a rehash of his articles, an operation I’ve always considered something of a cheat on the reader. This reader may have come across some of the ideas and starting points hidden in Severgnini’s articles. But the book is a complete rewriting of his experience and I know few who penetrated so far below the surface. I approached the manuscript with some trepidation because there has already been so much written about England and the English that it is hard to find anything new or original.

Yet Severgnini pulled it off, thanks perhaps to that very lack of experience that allowed him to see a complex country with fresh eyes. One feels that he got inside it and the portrait he paints will probably even please the English who will find in it all those eccentricities and contradictions they play up to underline their diversity.

Something of it stuck to him too, as if it were fated to happen. I don’t know of anyone who stays in England very long who isn’t affected by the country, especially if they go there when they are young. Many end up apeing the English, something the English loathe. But this didn’t happen to Severgnini, who took from them what they all should but few do: the use of understatement and that lowkey sense of humour which Italians are in such need of.

INDRO MONTANELLI

Milan, autumn 1989

Dedica

To Ortensia who accompanied me.

BEYOND MUSEUMS

I spent four years in England and I know the importance of visits from Italy. Experience has taught me that these visits can be divided into pleasurable visits and less pleasurable visits, long visits and short visits, the most demanding visits and relaxed visits. Among the least pleasant, busy and often seemingly interminable visits are the ones paid by the so-called Expert, who arrives equipped with very precise theories and very little experience. As he drags his suitcase through the arrivals hall at Heathrow, he is already explaining England to the natives. This type is living proof of something I’ve always suspected: the problem with London – one of the few problems – is that Italians think they know it well. It’s not only London they think they know. They also think they know the English language, the English, England, and Britain.

I remember a visit like this a while back from a particularly formidable Expert. This chap not only had detailed ideas about post-imperial British decadence and the urban development of London’s beltway, but he came armed with a deadly weapon, a Touring Club Italiano guidebook circa 1969. It was a grey hardback from the "Great Cities of the World" series and its title was "Here’s London". In 1969 and the years immediately following, the guidebook presented no problems. The researchers at the Touring Club, besides being scrupulous, were also gentlemen. They had no intention of providing the public with a means of torturing Italians living abroad. But by the time my guest withdrew it from his suitcase, his fifteen-year old edition of "Here’s London" had become dangerous. Here’s why: the Expert was determined to see everything mentioned in the book, even though some of it hadn’t existed for more than fifteen years.

A trip down the Thames to Greenwich was particularly enlightening. The Expert, leading us on with guidebook in hand, insisted he wanted to see the "the unvarying multitudes of audacious riverboats, ferries and barges" in the docks of London (page 19) and was irritated when he was told that he would have been able to see the multitudes of boats had they still existed and they would still exist if the docks still existed, but both had disappeared in the seventies, the docks replaced by luxury flats in Docklands inhabited by wealthy architects who passed the time staring out the window through binoculars at Italian tourists passing by with the 1969 Touring Club guide to London in hand. That’s when it hit me: maybe the time had come to update the book.

At this point the great American journalist, John Gunther, came to my aid. Many years ago, he suggested a way to write effectively about another country. Write as if it were for a man from Mars, who would want to know the most basic things: How do people live? What do they talk about? How do they have fun? Who’s in charge? In other words, don’t take anything for granted. This is especially apt for a country like England. Foreigners often arrive full of preconceived ideas: the English are reserved, they love tradition, they like to read, they hate to bathe. Over the course of a few days they discover that everything they thought is true. This discovery generates such euphoria that they go no further. Yet present day Britain should be approached with care. It is still a mysterious island and should be explored as one explores America, with eyes wide open, taking nothing for granted.

To begin with you must remember that no country in the world can be reduced to a city. Britain is not London. Even the things we think we know, from the black cabs to the royal family, change constantly. Many aspects of Britain are fascinating and yet overlooked, like the spectacular pyramid of the class system; the melancholy seaside; the bizarre behaviour of "young fogies", old by choice at twenty; dog races; and the charms of "the season" (Wimbledon, Ascot, and the picnics and opera at Glyndebourne) when the British pretend it’s summer.

We can assure the explorer that his efforts will be rewarded. Sixty years ago the English author of one of the innumerable travel books on Italy, E.R.P. Vincent, proved himself a perspicacious visitor with this simple remark: "Italia is not Italy". He was referring to the unchanging country of Botticelli and pergolas that generations of misty-eyed English travellers had described before him. "Italia" he went on, "has a future, Italy does not, it only has a scant present and an immense past. Italia has bitter icy winds, Italy basks in perennial sunshine. Italia is a strange, hard, throbbing land, Italy is accessible, straightforward and very dead." We can turn this around and observe that the Great Britain of parks, red double-decker buses and bobbies does exist. But there is another Britain, full of silent suburbs and restless minorities, of nouveaux riches and old habits. It too is worth study.

Describing this Britain isn’t the same as writing a tourist guide. It does mean providing honest information about what has befallen Britain over the last ten years as it come to grips with an onerous past and two prime ministers that no one anticipated. It also means recognising that Britain knows that it can no longer live on its laurels. It must now join the rest of Europe and become a normal European nation. In some cases, it means not taking the British too seriously, any more than they have taken the rest of the world seriously over the centuries.

Like all authors, I have one small hope: that for those of you who keep crossing the Channel to work, to study or to buy a sweater and have finally decided to skip the museums, this book will prove useful. And, who knows, perhaps the British themselves, looking at their image in this book, will discover that they are more interesting than they ever suspected.

WHERE IS BRITAIN HEADING?

THANKS TO NANNY THATCHER

For Britain, the eighties were the Margaret Thatcher years, just as the sixties were the Beatles years. The comparison isn’t meant to show disrespect either to Beatles fans or to admirers of Mrs Thatcher. The lady, like the lads from Liverpool, left an indelible mark on the country and the British remember her with a mixture of horror and admiration. One thing is certain: she’s not likely to be forgotten soon.

At the time of the leadership contest between John Major, Michael Heseltine and Douglas Hurd in November 1990, shortly after Mrs Thatcher’s resignation, a class of nine-year-old school children wrote to a newspaper to ask, "Can a man be prime minister?". The answer, as it turned out, was yes. Admittedly John Major, son of an acrobat, has not made much of a mark. Other former prime ministers have already been happily forgotten – James Callaghan, for example, is famous mostly for having made cat’s eyes obligatory in the middle of the road.

Not so Margaret Hilda Thatcher. Like Churchill and Elizabeth I before her, she belongs in the category of great leaders. Heroic as the statesman and tempestuous as the queen, she left an indelible mark on post-war Britain. This is not just a result of the length of time she spent in office but of her style of governing. There was no "Wilson-ism" after six years of Harold Wilson, just a bit more chaos. After four years of Edward Heath, no one spoke of "Heathism", only of a last ditch effort by the Conservatives to prop up a collapsing country. Yet after only three months of Margaret Thatcher, the term "Thatcherism" was in use. And still is today.

The lady took Britain by storm in 1979 and for the next eleven years she treated the nation with similar delicacy. During the 1980-82 recession, she came up with a revolutionary plan. Instead of stimulating demand, as prevailing economic wisdom dictated, she concentrated on cutting public spending and controlling inflation, and simply ignored the numbers of unemployed, calling them a necessary but passing evil. She argued that you had to produce wealth before you could distribute it and that task was up to the individual. The State had to stand aside and leave the responsibility and decision-making to him.

In Italy, where we were used to prime ministers whose ambition was to get through the summer, we were unnerved by a leader whose ambition was to get into the history books. In Britain, Thatcher’s adversaries suffered wounds from which they are only now beginning to recover. To its horror, the Labour Party realised that the lady was not going to be satisfied simply with defeating it at the elections; she meant to convert its followers. Many Conservatives hadn’t understood what kind of leader they had nominated and began to invoke Disraeli and his vision of a more compassionate society. The electorate on the other hand picked her three times (1979, 1983 and 1987) and – keep this in mind – never fired her.

Please note that it was her own party that expelled her from Downing Street. Whether they did the right thing, only time will tell. It may be true that Thatcher was authoritarian and ruthless, and that she defended Britain’s interests against the rest of the world with an embarrassing vehemence, but it is also true that she alone had the courage to tell the nation to its face what no other prime minister had dared: that Britain may have won the war, but it was behaving as if it had lost. In 1945, poor and exhausted, the country ceased to be a great power and at that point should have begun to transform itself into something else. With her election in 1979, Mrs Thatcher started to badger the country, nanny-like, into facing up to this new reality. She told Britain, one of the greatest imperial powers in history, that there was no shame in competing with the likes of South Korea over the production of cutlery; she told workers that, contrary to what Labour was telling them, not only was it no crime to want to own their own homes, it actually made sense; and she told the public that it was ridiculous to have defeated the Nazis only to be brought down by your own trade unions.

The results of eleven years of Thatcherism can be seen everywhere. Today’s Britain is a modern nation, moderately rich, reasonably quiet. It may have left its empire behind but it hasn’t abandoned it. Leaders of myriad small countries around the world, members of the Commonwealth, can still have their photos taken in front of Buckingham Palace. Britain’s new role was not forced upon it; it was a role Britain itself chose. (The Argentine generals didn’t recognise this shift in position in time; as a result of their error they were soundly thrashed in the icy waters of the Falkland Islands.) The turning point for the country came during the winter of discontent in 1978-79 when strikes prevented the dead from being buried and electricity was rationed. Exploiting the changing public mood, Margaret Thatcher seized the opportunity and declared that her values – individual economic initiative, national pride, order and respect for the law – were the values of the middle class and middle class values would be the country’s values. She was convincing. The lady had already revealed a quality rare in a politician: she said what she believed. As it turned out, what she believed, three times running, was also what her electorate believed.

Warnings of the approaching storm (for those who knew how to listen) had already sounded in 1975 when Margaret Thatcher was elected leader of the Conservative Party at a time when the Conservatives were in opposition. A few days after her nomination, one of her opponents described the first meeting of the shadow government this way: "As she touched up her hair and hooked her bag on the back of the chair, we were filled with a foreboding of impending calamity". Their foreboding was not unfounded. The Conservative Party of Macmillan and Heath was destined to disappear. Over the next fifteen years Margaret Thatcher completely changed the rules and the goal became one of seducing and winning over the lower-middle classes, from whence she had come, bypassing the traditional elite who claimed to detest her (actually they were rather fond of her, much as the nobility of the past was fond of their stewards: they may not have been likable, but they were still useful and necessary).

Today, the three largest political parties believe they have moved beyond the class system. This, however, is not true. The Labour Party still fishes mainly in working class waters and attracts young people who worry about social justice as they wait to earn a good salary. The Liberal Democrats attract mainly eccentrics, dissatisfied intellectuals, and the young. Only the Conservatives, moulded by the grocer’s daughter, then turned over to the son of a trapeze artist, have branched out decisively. Aware that they have only limited support among the upper classes, they have looked for votes wherever they can be found.

Examples of the phenomenon abound. While the central office of the Conservative Party in London’s Smith Square may still be full of well-groomed, well-dressed and bejewelled workers looking like they have just come from a party, things are different in other parts of Britain. Take Ealing, a suburb on the outskirts of London. Harry Greenway, the Conservative candidate in a recent campaign, looked like a used car salesman and he talked like a used car salesman. Many of his supporters probably bought used cars. But they were also tenants who had bought their own council houses, thanks to a law passed by the Conservatives, and they were old-age pensioners, convinced that the Labour Party had lost all respect for the police, and they were Pakistani grocers who particularly liked Margaret Thatcher’s injunction: make money and your bank account will make you equal.

In Liverpool a group of loyal supporters opened a tearoom called Thatcher’s where customers could celebrate that very British ritual under a portrait of the ex-prime minister. The idea enjoyed a modicum of success and showed – according to the ladies who ran it – two things. One, that the sight of Margaret Thatcher does not turn everyone’s stomach and two, that private initiative pays off everywhere, no matter what the opposition says. Neither the proprietors of the tearoom nor its customers were members of the landed gentry. They represented a middle class that has learned to adapt, one that is not convinced that all the troubles suffered in the north of England are the fault of the government.

In the City of London, far from the misery of Liverpool, hymns of thanksgiving were sung daily to the Conservative government in power. That this should have happened in the City was perhaps less surprising than when it happened in Liverpool, but this gratitude did not come just from bond traders hoping to see their earnings grow. After 1979, the year of the first Labour defeat, capital controls were abolished, taxes reduced, trade unions weakened, inflation kept in check and the value of the pound remained stable. The City hopes that with the European Union, Europe will become an enormous supermarket for British financial services. It is no coincidence that the City loves Europe as much as it loves the Conservative Party.

However, even the British who admired Margaret Thatcher most for having turned the nation around, felt little affection for her. The lady didn’t seem to have the peccadilloes of the average Englishman or woman and this made the public uneasy. That wasn’t all. Mrs Thatcher, unlike milder-mannered John Major, liked to be thought of as uncompromising and ruthless even when she was not (take her cuts in public spending: when all the accounts were added up and settled, they did not turn out to be drastic after all). "After years of self-indulgence, the country needs rigorous and harsh treatment: I will see to it." Over the years this attitude brought her numerous detractors and a sle...

Indice dei contenuti

- Copertina

- Frontespizio

- An Italian in Britain