eBook - ePub

Risk-Based Investment Management in Practice

Frances Cowell

This is a test

Condividi libro

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Risk-Based Investment Management in Practice

Frances Cowell

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

A practitioner's account of how investment risk affects the decisions of professional investment managers. Jargon-free, with a broad coverage of investment types and asset classes, the non-investment professional will find this book readable and accessible.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Risk-Based Investment Management in Practice è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Risk-Based Investment Management in Practice di Frances Cowell in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Negocios y empresa e Finanzas corporativas. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

Negocios y empresaCategoria

Finanzas corporativasPart 1

Introduction

1

Introduction

Investment management is one of the few highly paid professions for which no formal qualification is universally recognized. Yet few people would dismiss the responsibilities of investment managers as simple or trivial. Even evaluating the quality of their work is complex and inexact.

Professional investment management is relatively recent and for the first half of the twentieth century was confined to a limited range of investment techniques and instruments. That started to change in the second half of the century: financial instruments have proliferated and become more complex and markets have become more volatile, for example.

Yet derivatives were used in the Middle East in ancient times, in the markets in Rotterdam in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and in the USA during the 1930s. With inferior information and non-existent supervision and regulation, many of these early investments carried risks that would be unthinkable today.

Markets appear more volatile now than they used to be – but there has never been a time when investments did not sometimes go wrong, because there was never a time when people were infallible. Soundness of judgement has always been subject to compromise; alchemy was once regarded as a trusted mainstream science. Before the invention of the telegraph, markets would swing violently on rumours during wars. Investors from time to time seemed to behave irrationally, giving rise to investment ‘bubbles’, which burst – ‘inevitably’. One need only be reminded of Tulipmania to realize that this is by no means a modern phenomenon. Many people today know somebody who became rich or poor, or both, as a result of the Poseidon boom in 1966.1

Markets are perceived to be more global nowadays, with large capital flows to and from emerging markets such as South America and South East Asia. In this trading environment, currencies can appear to be growing ever more volatile. Certainly international capital flows are greater nowadays than they were in the twentieth century, when most countries were subject to controls on international capital movements and very high transactions costs, but currencies were not necessarily less volatile. Prior to World War I, international investment was a major source of wealth to the economies of the Old World. The South Sea Bubble, the Dutch East India Company and the British venture that followed it are some examples. The very purpose of Columbus’ voyage was to seek access to new markets and investment opportunities in East Asia. The Romans accumulated vast investments outside their home country, trading in places as far away as Africa and South East Asia. It is true that money moves about the globe much faster now than it used to, but so do goods – and people.

Some major changes have occurred however. One is that investments are much more widely held than even a few decades ago. In most western countries, investors now come from all backgrounds. People who grew up in developed countries after World War II, rich and poor alike, have collectively accumulated vast sums of personal savings, either privately or in company or government sponsored pension funds, mutual and trust funds and elsewhere. Investments are no longer the preserve of the very wealthy. Since these investments will, for the majority of investors, one day be their primary source of income, risk control and accountability are more important than ever before. The average investor has a fairly low tolerance for losing money and, because there are now large numbers of ‘average’ investors who vote, governments take an increasingly active interest in seeing that things do not go too horribly wrong. This ‘democratization’ of investment management is driving the imperative for greater accountability and risk control.

Another important difference between these and earlier decades is the way in which advances in technology have increased the amount of available information and transformed the way it is used and transmitted. The communications revolution speeds up funds flow around the world, sometimes even challenging governments and monetary authorities to keep up with appropriate policy responses.

The ability to analyse data in bulk encouraged the development of new ways of applying it to gain insights into the behaviour of investments. Thus we see an increasing number of investment modelling techniques, based on advanced mathematics, which are not immediately comprehensible to many investors.

The purpose of this book is to examine how investment theory developed since the middle of the twentieth century has improved understanding of the relationship between risk and investment outcomes, and how this understanding is used to select investment portfolios. This chapter gives an overview of some of the issues that usually determine investment management objectives and precede the investment selection process.

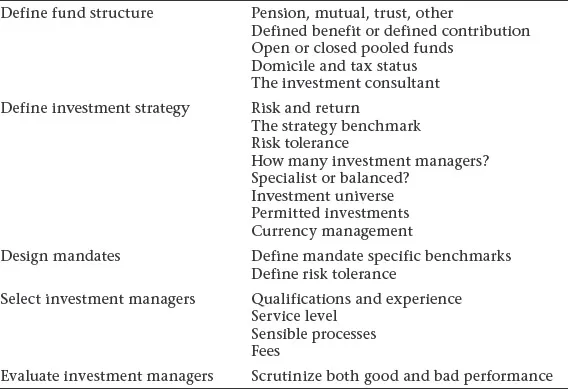

Table 1.1 Typical investment management process

A typical investment management process might look something like Table 1.1

Defining the investment fund structure

Individual investors may choose to do their own investing, by purchasing stocks and bonds or investing in specialist funds, trusts or investment companies on their own behalf, or they may follow the advice of their stockbroker. To accommodate tax or other legal considerations they may choose to engage a financial planner or tax expert. At the other end of the spectrum are investors entrusting their savings to professional investors, usually large institutional investors, such as mutual funds, pension funds or insurance companies, who typically provide a package of research, investment strategy, structure and administration.

Many investors invest in small and medium-sized pension funds and other pooled funds. These funds make use of a mixture of external and in-house advice for tax and economic analysis. Because different kinds of investment funds can cater to different fiduciary and tax requirements and constraints, the investor is usually faced with enough choice of investment funds to ensure a reasonable fit with his or her investment requirements.

For pension funds, mutual funds, trust funds, investment companies and other pooled funds, how investments are structured depends on the objectives and constraints of the majority of investors. Issues that are usually taken into account when devising investment structure for a fund are:

•The expected investment horizon.

•Cash flow and other liquidity requirements.

•Domicile and tax status.

•Minimum investment required.

•Any special ethical or legal constraints?

The investment horizon can range from a few months to many years. For example, pension funds tend to have long investment horizons, reflecting the expected length of the working and retirement lives of their members, while mutual and trust funds generally have short horizons, reflecting investors’ preference to trade in and out of them regularly.

Liquidity requirements can be driven by the membership profile, as in the case of mature pension funds, perceived market demand or tax status. The question of income versus capital growth tends to be closely aligned with the tax status of the fund, and this in turn affects the choice of domicile.

Many funds stipulate minimum investment amounts, both for initial investment in the fund, and for subsequent investment and withdrawal. The purpose of these limitations is usually to contain the manager’s administration costs: the cost of administering a $1000 investment is the same as a $1 000 000 investment. But, because administration is usually charged to the investor as a percentage of the sum invested, minimum investment amounts are set to ensure that administration fees cover their cost to the investment manager.

Ethical funds have enjoyed increasing popularity in recent decades. Investors have the choice of avoiding financing arms manufacturers, tobacco companies and organizations engaging in environmentally contentious businesses. Sometimes legal limitations are imposed on the fund; for example, many corporate pension funds are prohibited from owning large interests in the company itself.

Fund structures

The main fund structure types are:

•Defined benefit or defined contribution.

•Open or closed.

Defined benefit, or final salary, funds assure the investor a fixed payment at the end of the investment period, that will be paid either as a lump sum or an annuity. The investor’s contribution to the fund may vary over time as the fund’s total value fluctuates according to varying returns on its investments. Managers of defined benefit funds usually maintain a reserve as part of the fund to smooth the impact of withdrawals and disappointing investment returns.

When reserves do get too high relative to the estimated future obligations of the fund, the fund manager may declare a ‘contribution holiday’ – a period during which investors pay lower contributions than normal, or none at all, until the reserves again reach an acceptable level. This practice runs the obvious risk of being unfair to some investors while providing a windfall to others. It can also give the impression that the fund is unacceptably volatile, and reduce fund member confidence in the fund’s manager and administration. To reassure investors, some defined benefit funds build into in the investment strategy guarantees, either of capital or minimum returns.

The fund’s future obligations, also known as its liabilities, are valued using a Discounted Cash Flow procedure (an example of which is given in Chapter 3). This means that the value of the fund depends not only on the nominal amount held in the fund and its reserves but also on its future obligations and the discount factor used to value them. Funds with long-dated liabilities can be very sensitive to changes in the...