![]()

1

Wanderlust

THE FAIR-HAIRED YOUNG MAN shivered against the cold, despite wearing three sweaters and two pairs of pants. The sky, no longer ashen, stretched a deep blue above the North Sea. The explosion of icy sprays that had drenched the deck of the steel cargo boat for the better part of the transatlantic crossing had finally stopped. “Our portholes are fifteen feet above the water, yet only for the last two days they have been open, as the waves have smacked against them unceasingly,” wrote twenty-one-year-old Richard Halliburton from aboard the Ipswich in July 1921.1

The smell of grease and grime seeped through the Ipswich. It permeated everyone’s clothes with a mechanical stench. Halliburton didn’t mind; there was no place he would rather be. Standing watch on the bridge, he hoped to be the first to sight land.

Thousands of miles away in Memphis, Tennessee, in Halliburton’s boyhood room, stacks of geography and adventure books filled the bookcases. For years, the stories like those recounted in his well-thumbed Stories of Adventure transported him far from Tennessee. He had tilted at windmills alongside Don Quixote and slain dragons alongside St. George. With his light blue bound geography book as his magic carpet, he had virtually visited every country in Europe and most in Asia.2

Reading about author Harry Franck’s 1913 adventures as a Panama Canal Zone policeman thrilled him, but it also sparked a competitive streak. Halliburton vowed he wouldn’t just visit the canal someday, he would swim its length. Reading about Mount Fuji, he swore to scale its peak. Now he stood not just on the bridge of the Ipswich but also on the verge of living his dreams. He felt an obligation to his own curiosity, and travel was how he could fulfill that.

Meanwhile, his parents, Wesley and Nelle, waited anxiously for word from their son. Their unease weighed on Richard, and ever mindful of their apprehension, he continued to write home often. On the ship, he clambered down the metal stairs to his cabin and settled his lanky frame on his bunk. He meticulously chronicled everything he experienced, smelled, and saw. He wrote home about his impressions of people and places, and confided his angst and excitement. Halliburton stuffed the unfinished letter into his canvas knapsack, which held maps, a compass, a few changes of clothing, paper, and pens. He would post the letter as soon as the ship reached its port of call in Hamburg, Germany. He liked picturing his parents sitting in their living room and slicing open another one of his envelopes.

On July 19, 1898, Wesley Halliburton, twenty-eight, took Nelle Nance, twenty-nine, as his wife in a small ceremony at the Methodist Church in Brownsville, Tennessee, just fifty miles north of Memphis. They would enjoy fifty-three years of marriage. However, by Wesley’s account, he wasn’t desperately in love with Nelle when he walked her down the aisle. They balanced each other and grew to depend on one another. Time burnished their feelings to a deep admiration and love.3

Two years later, on January 9, 1900, Richard Halliburton was born in an old redbrick house. When Richard was still an infant, his parents moved to Memphis, a segregated city, where cotton was king and juke joints lined Beale Street. Wesley hoped to make money buying and selling land in east Arkansas, but the land didn’t sell. Then, just when Wesley and Nelle decided to pack it in and move back to Brownsville, some timber on the property sold. It was a fine reversal of fortune.4 The three then moved into the Parkview, a ten-story apartment building on Poplar Avenue. Now a retirement home, the same copper awning still juts forth, aged to a mint-green patina, and large floor-to-ceiling windows line the first floor. Just steps from leafy Overton Park, the building perfectly suited the young couple with baby in tow.

Intellectually curious, the couple adored traveling and infused their son with a quest for knowledge. They were an upper middle-class couple, both coming from solid families.5 Wesley Halliburton Sr. was of Scottish ancestry. The name Halliburton traced to an ancestor named Burton who built a chapel for his village in Scotland, and thereafter became known as “Holy Burton,” which eventually evolved into Halliburton. An avid outdoorsman, Wesley had a penchant for hiking. In 1891 he graduated from Vanderbilt University with a degree in civil engineering.

French Huguenot and Scottish blood ran through Nelle Nance. She had graduated from the Cincinnati College of Music and taught music at a women’s college in Memphis. Always active in her community, be it sitting on a committee or chaperoning a clutch of girls to a symphony or a trip to Europe, Nelle served as the Memphis chapter’s president of the Nineteenth Century Club, a philanthropic and cultural women’s club. Many notable people passed through the double doors of this classic redbrick building with fluted columns. A gracious lady, as Halliburton’s friends described her, Nelle appreciated social standing and the importance of connecting with people, traits her son would share. Wesley Halliburton, too, displayed the “stuff of which his illustrious son was made,” his own curiosity about the world that was reflected in his oldest son.6

Halliburton had no living grandparents. The closest he had to extended family was Mary Grimes Hutchison, dean of the all-girls day school he attended. Indeed, Richard Halliburton was the only boy ever admitted to the college preparatory school. While his parents called Mary “Hutchie,” Halliburton nicknamed her Ammudder—his way of saying “another mother”—when he was small. Throughout his life, he frequently wrote to her. She remained a constant and nurturing presence. Acting the doting grandmother, Hutchison often tucked money into her letters, always asking after him, spoiling him.

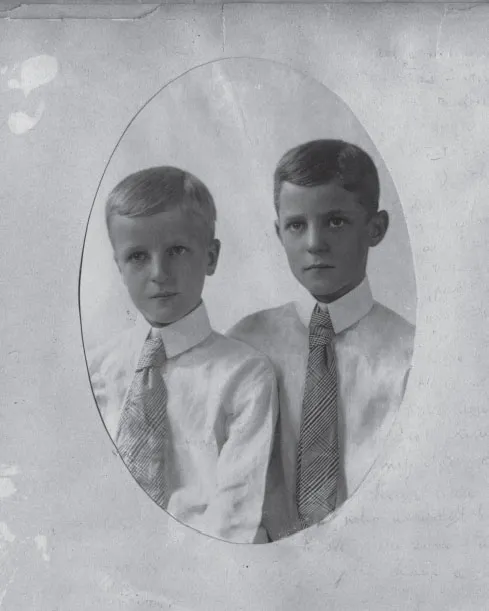

On May 31, 1903, Wesley and Nelle welcomed Wesley Jr., and the small family was now complete. With their fair hair, brown eyes, and lanky limbs, the brothers thoroughly resembled each other in looks, if not temperament. Whereas Richard was a mediocre violinist and a keen golfer, his brother favored baseball. Whereas Richard was outgoing, his younger brother was more reserved.

Brothers Richard and Wesley Jr. were three years apart. Princeton University Library

Throughout his early childhood, Halliburton’s most trusted companions were a pony called Roxy and his dog Teddy. Teddy padded behind Halliburton on his way to track, baseball, and football—and often outdoors to explore.

Loving parents, Wesley and Nelle encouraged their boys to be interested and interesting. The family of four often traveled, and young Richard saw a world beyond the borders of the southern city. One of his most exciting moments was his first trip to Washington, DC, when he was fifteen. “Woodrow Wilson was then President, and to my vast delight, as a special favor, I was taken to the White House, right into the President’s office, and introduced to him. My fingers trembled a little when we shook hands … to me he was the greatest man in the world. He was the President.”7 Richard also especially relished time spent at the Biltmore Hotel in Asheville, North Carolina, where nearby he and his father hiked the low rolling hills and rambled along trails in the Pisgah National Forest. Richard Halliburton desperately wanted to strengthen his slight frame.

Unexplained health problems beset Halliburton from a very young age but came into full force when he was about fifteen. He tended to get breathless and fatigued. He tried to ignore his racing heartbeat. He frequently watched his friends from the sidelines. His malady perplexed and worried his parents. They often reminded their elder son to take it easy, and at one point the adolescent spent four months in bed. Still his health showed no improvement.

The thought of living a cautious life vexed young Halliburton, who, though quiet on the surface, fancied danger. When he was just five years old, a runaway pony dragged him several yards. Nelle recalled feeling petrified her little boy would die. But afterward the little boy was not only calm, he acted as if being dragged by a pony was as normal as being pulled along in a little red wagon. “After that wild ride his life was one escapade after another. Even in play, only the dangerous things appealed to him,” she recalled.8

The Halliburton family doctor recommended that the sick teenager seek treatment at the famous Battle Creek Sanitarium, so the Halliburtons drove their son to Michigan. There, doctors treated him for probable tachycardia and an overactive thyroid.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and his brother William Keith Kellogg had opened the Battle Creek Sanitarium in 1866. The institution’s treatments included low-fat, low-protein diets, exercise, cold-air cures, and hydrotherapy. The Kellogg brothers modeled their new sanitarium after European spas with their water cures and mineral baths. In time, the sprawling complex in America’s heartland was a place to which the rich and famous retreated to get well. Celebrated American figures including Mary Todd Lincoln, Amelia Earhart, President Warren Harding, and Henry Ford all spent time at the facility for various ailments, physical and mental. Years after Halliburton’s successful stay there, his parents returned to the sanitarium to rest and diet on and off for thirty-seven years.9

The exercise—including swimming, calisthenics, and gymnastics, coupled with rest—seemed to help Halliburton. And being away from home for the first time did nothing to curb his taste for independence; instead, his stay at Battle Creek whetted his appetite for adventure. Lying awake on his thin mattress each night, Halliburton fantasized about floating down the Mekong River in Indochina and living as Robinson Crusoe on a deserted island. In his dreams, he was Joseph Conrad penetrating the Heart of Darkness or the poet Rupert Brooke writing of war, youth, and longing.

He pondered his future and realized he wanted a different life from his father. Rather than enroll in nearby Memphis University School and then matriculate at Vanderbilt University, as his parents expected and as two generations of Halliburtons had before him, Richard yearned to attend Princeton University. He begged his parents to let him go to New Jersey and enroll in Lawrenceville Academy, an all-boys boarding school. This would increase his chances of being accepted to nearby Princeton. He had met other young teens at Battle Creek who attended Lawrenceville, and their love and loyalty to the school impressed him. He had to attend, he told his parents. He craved that sense of brotherhood, so with his parents’ blessing Richard enrolled in 1916.10

Lawrenceville Academy may not have been Halliburton’s idea of a wonderland—it had rules, after all—but nevertheless, he delighted in his newly won independence and earned excellent grades. During his years there, he became editor-in-chief of the school’s newspaper, the Lawrence, and was chosen to write the words and music for the class ode. He made fast friends with Irvine “Mike” Hockaday, John Henry “Heinie” Leh, and James Penfield Seiberling of Akron, Ohio, who was the son of F. A. Seiberling, founder of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. Everyone called Seiberling “Shorty,” and Edward L. Keyes, the son of a New York physician, became “Larry.” Channing Sweet was “Chan” and Halliburton became “Dick” to his friends. These were lifelong friendships in the making.

Each year about fifty Lawrenceville students went on to Princeton University. In the fall of 1917 Halliburton and his friends were admitted to the prestigious institution and moved six miles down the road into a large suite inside the stately dormitory at 41 Patton Hall. During their first year, the friends resolved to write an annual Christmas letter as a way to reflect on the year past and look forward to the next. They maintained the tradition well into the 1960s.11

“As young men in the prime of health, we were energetic, robust, zestful individuals, but otherwise quite dissimilar with respect to talents and tastes,” Seiberling recalled many years later. “For the most part we each engaged in developing our own special aptitudes and in pursuing our own particular interests.”12 Of the six of them, Halliburton was undoubtedly the most exceptional, Seiberling said. He had a fine intelligence and active mind. He was alert, inquiring, imaginative, and inventive.13

Halliburton had started writing at Lawrenceville—short stories, poems, and essays—and continued at Princeton. He worked on the Daily Princetonian newspaper and the Princeton Pictorial Magazine, a.k.a. the Pic, a publication featuring student essays and photographs. A quote from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray inspired him: “Realize your youth while you have it…. Don’t squander the gold of your days.” For the young Halliburton, following a corporate path would be to squander the gold of his days. The notion itself was stultifying. An idea germinated in Halliburton’s mind: perhaps his future lay in writing.

When Halliburton left for Princeton, his younger brother, Wesley Jr., took his spot at Lawrenceville. Three years younger, Wesley Jr. was the quintessential kid brother. He idolized Richard and bounded after him with exuberance. Devoted to baseball, Wesley Jr. always kept his well-oiled mitt buckled to his belt. Richard was proud of his brother, and the family of four delighted in each other’s company.

Then in November 1917 their world irrevocably fractured. Wesley Jr. fell ill. A few weeks before t...