eBook - ePub

Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark

From The Kingdom to The Killing

Kenneth A. Loparo

This is a test

Condividi libro

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark

From The Kingdom to The Killing

Kenneth A. Loparo

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Offering unique insights into the writing and production of television drama series such as The Killing and Borgen, produced by DR, the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, Novrup Redvall explores the creative collaborations in writers' rooms and 'production hotels' through detailed case studies of Denmark's public service production culture.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark di Kenneth A. Loparo in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Media & Performing Arts e Film & Video. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

Media & Performing ArtsCategoria

Film & Video1

Television Writing and the Screen Idea System

Introduction

Where do ideas for television series come from? How do writers, producers and broadcasters settle on the ideas to pursue and what are the stages and challenges in developing ideas into series for the screen? One would think that questions like these about the choices of practitioners and the nature of production were central to film and media studies, yet limited attention has been given to the creative process of developing and producing new works of fiction, let alone to the study of these in television.

One method that can prove useful for addressing such questions is, I argue, a Screen Idea System framework. This chapter introduces the Screen Idea System framework for the book, which builds on an understanding of the writing and production of television as a complex interplay between individuals, a domain and a field. The book links theories from film and media studies, approaches from the emerging area of screenwriting research, with concepts and models from the field of creativity research, insisting that one always needs to take what could be called ‘the many P’s in production’ into account when analysing the emergence of new scripted series. Creativity scholars argue that when trying to understand the nature of creative work one has to include the Process, the Product and the Press and the understanding of the Person, with ‘Press’ referring to the environment in which the creative work takes place. This is the so-called ‘four Ps’ of creativity (see, e.g. Rhodes 1961; Mooney 1963).

Approaching the writing and production of television drama from this perspective, the chapter addresses how to understand this interplay as a system where individuals with a specific talent, training and track record propose new screen ideas as variations on the existing trends, tastes and traditions in a domain, which then have to be regarded as being of high quality and appropriate in order to be accepted by gatekeepers with a specific mandate for production. A special focus of this chapter is the collaborative processes of television writing, analysed as the work of ‘thought communities’ who go through different stages in a problem-finding and problem-solving effort when moving from an original idea to a final product.

Studying television writing and production

While film and media studies do not have a tradition of extensive case studies of the nature of creative work, other fields of scholarship have taken a greater interest in the nature of artistic and cultural production. Sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Howard Becker have written extensively on the field of cultural production and on art as collective action or ‘art worlds’ (e.g. Bourdieu 1993, 1996; Becker 1974, 1982). Sociologist Leo Rosten and anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker were among the first to conduct production-oriented studies of the American film industry (Rosten 1941; Powdermaker 1950).

More recently, studies coming from a ‘production of culture’ perspective have focused on how creative work in the cultural industries is the result of complex patterns and collaborations rather than a clear result of one person’s vision (e.g. Peterson and Anand 2004), and this collective perception of cultural production also marks other cross-disciplinary publications and current studies of the nature of work life in the creative or cultural industries (e.g. Negus and Pickering 2004; Deuze 2007, 2010; Hesmondhalgh 2007; Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2010). These scholars are not alone. Coming from organizational studies, researchers like Paul DiMaggio and Paul M. Hirsch (e.g. DiMaggio and Hirsch 1976; DiMaggio 1977) have been investigating the structures in the cultural industries for quite some time, while others have been looking more specifically at film and media production, for instance, Helen Blair analysing work conditions in the film industry (Blair 2001, 2003).

Whereas the collective nature of most cultural production and the work processes in different cultural industries have interested researchers for a number of years, few studies combine this interest with the development of a specific product or the nature of the product itself. As noted in a sociological study of different processes of art making ‘from start to finish’ there has, for instance, always been ‘a blind spot in the sociology of art: any discussion of specific art works’ (Becker et al. 2006, 1). While the humanities tend to emphasize the text over practice, the social sciences tend not to include the text, or the product, in the analysis. There are exceptions, and some media industry research has addressed questions about the impact of particular modes of production on what is actually produced, for example, David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson’s seminal study The Classical Hollywood Cinema on the organizational conditions as well as the stylistic and storytelling structures in Hollywood until 1960 (Bordwell et al. 1985). Studies like Thompson’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) or Bordwell’s The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006) have constructively argued how particular modes of production influence storytelling strategies with much more detail on particular products than will be offered here. This book does take an interest in the development of specific series, but the product as such is not thoroughly investigated for formal-aesthetic qualities.

The focus of this book is on a certain mode of writing and producing television drama. Building on the work of previous scholars, the goal is to provide more detailed analysis of the actual writing and production process, emphasizing the value of production analysis of creative collaborations to further understandings of how new television works come into being. Production analysis can take many forms and range from macro to micro levels, from political economy to professional routines (Newcomb and Lotz 2002). Most production analysis operates with several levels of analysis simultaneously to capture the complexity of the production process. Specific case studies are often central to the analysis, as Horace Newcomb has discussed (1991) comparing three classic examples of television case study research with different approaches (Cantor 1971; Elliott 1972; Gitlin 1983). Questions regarding the degree of creative freedom and the organizational and financial framework are central in all of these three classic studies, as is the case in more recent research (e.g. Levine 2001; Lotz 2004). As Newcomb has noted, the driving question in most production studies, then as now, is to make sense of the cultural industries with the many problems related to ‘creativity and constraint in industrial settings’ (2007, 129).

Most studies of film and media production are reconstructions of past events based on interviews and document analysis rather than observations or conversations during productions. An example is film scholar Robert L. Carringer’s book The Making of Citizen Kane (1996), which among other things explores the complicated relationship between the young Orson Welles and the experienced screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, leading to Mankiewicz not receiving a credit on the film until The Writers Guild looked at the matter. Much can be learned from this kind of retrospective data gathering, but it is hard to gain a nuanced understanding of the specific nature of the creative collaborations and processes from this approach. Behind-the-scenes publications on legendary productions can offer insights, like Steven Bach’s account of his time as a producer with United Artists during the making of the famous failure Heaven’s Gate (1980) (Bach 1985), but books like these are of course written from an insider’s perspective. They offer back story details from the process of production, but without academic analysis to nuance the understanding of choices and events.1

The complexity of studying production leads Newcomb to argue for what he terms ‘synthetic media industry research’, comparing media work to a dance, where one has to focus on ‘movement, fluidity, and choices, both strategic and tactical, in any situation’, since the processes are marked by ‘constantly shifting involvement and engagement of individuals and groups who are always exceptionally aware of both the structures in which they work and the degrees of agency they hold’ (Newcomb 2009, 269). The question is, of course, how to study this kind of fluid process, where practitioners make choices based on their assessment of many different parameters in specific situations. This book follows researchers such as Robert E. Stake, who has emphasized the value of specificity and particularity when doing qualitative case studies in natural settings (2000, 2005) and when trying to interpret what is sometimes described as ‘meaning in action’ (Jensen 2002, 236). A fundamental challenge is how to design a research framework suited to break down the complex processes, when practitioners are choosing special paths and not others for the projects at hand.

Production as problem finding and problem solving

One way forward can be found in the work of David Bordwell, who has insisted on not forgetting the social practice and individual choices related to film and media production. Together with Noël Carroll, he has proposed a problem-driven, ‘middle range’ approach to film scholarship, where one defines a problem within the domain of cinema non-dogmatically and sets out to solve it ‘through logical reflection, empirical research, or a combination of both’ (Bordwell and Carroll 1996, xiv). As John Thornton Caldwell has argued, one can regard this approach as ‘workmanlike, specific, delimited, and local’, drawing on a pragmatic and process-driven perspective (2008, 25).

Bordwell has suggested that a fruitful strategy for conducting this kind of scholarship is to focus on the many choices by practitioners in the process through a problem/solution frame of inquiry ‘granting a role to the artist’s grasp of the task and of her own talents as well as to the possibility of errors, accidents (happy or unhappy), unintended consequences, spontaneous and undeliberated actions, and decisions made for reasons not wholly evident to the agents’ (1997, 150). Bordwell places special focus on the decision-making processes of film and media practitioners, along with the idea that decisions are made in social situations with specific demands. As he points out: ‘The artist’s choices are informed and constrained by the rules and roles of artmaking. The artistic institution formulates tasks, puts problems on the agenda, and rewards effective solutions’ (1997, 151). Furthermore, he discusses how artists draw on traditions and certain norms in their present time as the starting point for creating something new.

Bordwell’s problem/solution framework of inquiry shares many similarities with influential theories from the field of creativity research. Cognitive studies of creativity have often regarded creative work as a form of problem solving. A problem can be defined as ‘a situation with a goal and a hindrance’ (Runco 2007, 14). If one has a clear cut problem, one can move on to problem solving immediately, but in many artistic processes choosing the problem to actually solve will often be central to the process. What painting should one paint? What film should one make? As the American philosopher John Dewey has famously stated, ‘a problem well put is half solved’ (Dewey in Campbell 1995, 48). A number of creativity scholars have focused on problem finding in artistic processes to investigate why and how an artist decides to focus on one problem and not another (e.g. Csikszentmihalyi and Getzels 1976). The studies highlight the importance of the often underestimated phase of defining what problem to actually solve, which in the context of this book can be regarded as the important stage of conceptualizing what series to write and how to go about it before the actual execution of the plans.

Scholars coming from the school of Creative Problem Solving (CPS) have offered numerous models for how to understand creative processes in an attempt to clarify the movement from the mess-finding, data-finding and problem-finding stages of defining a problem through the idea finding to the solution and acceptance-finding stages of a task at hand.2 I have previously used models from CPS (Isaksen and Treffinger 2004) to break down the stages of development, writing and production in feature filmmaking when doing detailed production studies of the nature of each stage and exploring what makes the diverging ideas of each stage converge and move on to the next stage (Redvall 2009, 2010a). The case studies of this book are not structured around the stages outlined by CPS, but aspects of CPS are referred to, when for instance analysing the amount of time spent in the early stages of a problem-finding effort during research and development or differences in the approach of writers and producers as to when they expect solution finding and acceptance finding in terms of ascript.

From the problem/solution framework suggested by Bordwell and ideas of creative processes from CPS, one can derive a picture of television production as marked by individuals making choices in a collaborative work process; choices that are marked by the works already produced as well as by the different types of constraints surrounding the process. This approach insists on the ever-present importance of the social as well as institutional context when dealing with creative work.

Studying creativity in context

Most definitions of creativity focus on the ability to produce something that is new (e.g. original, unexpected) and is of a high quality and appropriate (e.g. meets task restraints) (e.g. Weisberg 1993; Sternberg and Lubart 1999). The concepts of ‘novelty’ and ‘value’ are thus central to this understanding of creativity (Mayer 1999, 449). Whether something has value or not is in many definitions linked to the outside recognition of the work produced and thinking about the relationship between issues of novelty, quality and appropriateness is useful for analysing the negotiations of what one intends to produce in a film and media context.

Early understandings of artists and their processes were based on mystical or religious explanatory frameworks with creative individuals often being regarded as geniuses (Sternberg and Lubart 1999, 5). Either you were blessed with the gift of creativity or you weren’t. The 1920s saw a shift from discussing the idea of the genius towards discussions of different degrees of giftedness in the attempt to study whether one could find specific personal traits or patterns of thought in especially talented or intelligent people (Ryhammar and Brolin 1999, 261). The research of the psychologist J. P. Guilford is normally defined as the starting point for the scholarly field of creativity research (e.g. Sternberg 1999). His approach was to study whether specific personal traits characterize creative individuals. This psychometric perspective and the focus on the individual and cognitive aspects of creativity were dominant until the 1980s, when both a social-psychological and a systems approach of creativity emerged, often termed ‘confluence approaches’ (Sternberg and Lubart 1999, 10).

The work of the Hungarian/American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi embodies this move towards including contextual elements in the understanding of creativity. His systems view of creativity is based on the conviction that creativity cannot be studied by isolating individuals and their work from the social and historical surroundings. Explaining the emergence of his so-called ‘systems model’ of creativity, Csikszentmihalyi has described how his early research focused on individual thought, emotions and motivations. Gradually, the task became more frustrating since it turned out to be to explain particular aspects of his data. As an example, he mentions how one of his studies concluded that the female students in an art school showed the same creative potential as their male colleagues. However, 20 years later none of the women had earned the recognition as outstanding artist to the same degree as their male counterparts (1999, 313).

Observations like these prompted him to design a systems model for creativity, building on the notion that creativity is never the result of individual actions alone, but:

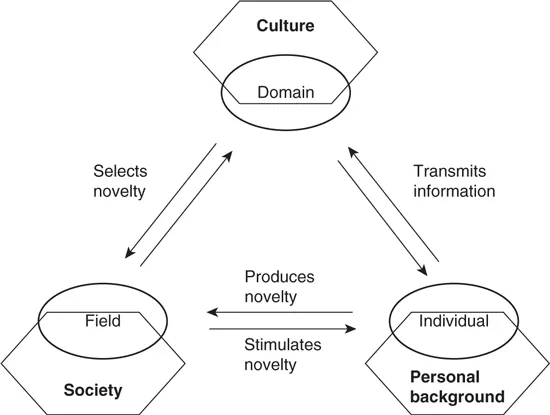

the product of three main shaping forces: a set of social institutions, or field, that selects from the variations produced by individuals those that are worth preserving; a stable cultural domain that will preserve and transmit the selected new ideas of forms to the following generations; and finally the individual, who brings about some change in the domain, a change that the field will consider to be creative.

(Csikszentmihalyi 1988, 325)

According to Csikszentmihalyi, creativity is thus the result of an interplay between these three forces, which he visualizes as follows (Figure 1.1).

The domain is to be understood as a formal system of symbols based on information that can be regarded as ‘a set of rules, procedures and instructions for actions’ (Abuhamdeh and Csikszentmihalyi 2004, 33). If one does not have access to the information within a certain domain, one is unable to contribute with new knowledge. As an example, Csikszentmihalyi mentions the difficulty of composing a symphony with no prior knowledge of music or of being acknowledged as a gifted mandarin chef without knowing anything about the Chinese cuisine (1988, 330). Some domains have a structure, which makes them hard to enter and renew, while others are more accessible. Within the domain of film and media production, there are, for instance, particular understandings of best practice, such as classical storytelling strategies, which one will be measured against when proposing a new variation. Moreover, existing works within the domain shape the understanding of quality among the individuals wanting to create new variations as well as among the experts assessing their value.

Figure 1.1 The systems model by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi3

The field is the social aspect of the model and encompasses the individuals who function as gatekeepers by deciding whether a new idea or a product should be included in the domain (1999, 315). In a screenwriting or television drama context, screenwriting and production teachers, critics, journal editors, script editors, commissioners or network executives are examples of people in key positions, enabling them to choose which works deserve to be produced or recognized, broadcast and remembered. The individual is the third element in the system. According to Csikszentmihalyi, one can speak of creativity when a person uses the symbols in a specific domain, gets an idea, sees a new pattern or creates something new, which by the appropriate field is found worthy of being in the relevant domain. Based on this systems approach, he defines creativity as ‘any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms an existing domain into a new one. And the definition of a creative person is: someone wh...