![]()

1

Captain James Wallace Terrorizes Narragansett Bay

April 1775 to April 1776

WALTER CHALONER’S SPY RING

In early 1774, Captain James Wallace, commander of the twenty-gun Royal Navy frigate Rose, went to work enforcing British maritime laws and capturing smugglers in Narragansett Bay. Once hostilities between the British and Americans broke out at Lexington and Concord on April 5, 1775, Wallace launched a yearlong campaign to intimidate Whigs and dampen their rebellious spirit. His ship—reinforced at times by the twenty-gun Glasgow, the sixteen-gun Swan and the ten-gun bomb brig Bolton—seized unsuspecting merchant ships as prizes; threatened to burn Newport to the ground (resulting in many of its citizens fleeing the port for the remainder of the war); bombarded the port of Bristol, to the north, until its citizens provided him with sheep; raided Jamestown, burning some fifteen houses and killing an eighty-year-old man; and plundered farms fronting the southern Rhode Island coast for their sheep and cattle. For his efforts to suppress the rebellion in Rhode Island, Wallace was later knighted by King George III.1

Wallace was aided in his work by a number of prominent area Loyalists, including men such as retired merchant Robert Ferguson. In 1750, Ferguson had moved from Scotland to Newport, where he engaged in the “Guinea Trade”—each year sending out a single ship to purchase slaves on the African coast and carry them across the Atlantic Ocean. After the end of the Revolutionary War, in Ferguson’s application for reimbursement of his war losses, Wallace informed the Royal Commission in London that Ferguson was “very loyal” and that he had “often received very useful intelligence of ye designs of ye rebels from” him and Captain James Keith.2

While Wallace terrorized Narragansett Bay from April 1775 to March 1776, a Continental army, ultimately commanded by George Washington, surrounded Boston and penned in British forces there. This led to two spectacular episodes of spying in Newport.

Walter Chaloner lost the office of sheriff of Newport County in 1774, after being elected to the post for seven years, due to his strong Tory sympathies and the increasing Whig influence. In 1786, he wrote down the story of his efforts to establish a spy ring designed both to keep Wallace apprised of the latest intelligence and to bring escaped Loyalists from and near Boston to safety on board one of Wallace’s ships in Narragansett Bay. Assisting Chaloner were two trustworthy men, “one a bold, active white man by the name of [William] Crossing, formerly a deputy sheriff under him, and the other a black man.” For almost a year, Crossing and the unnamed black man frequently ferried to Wallace Loyalists “who had made their escape out of Boston” and “who were obliged to seek shelter on board His Majesty’s ships for the safety of their lives.” “The danger attending the service being great,” Crossing and his assistant “were obliged to perform the business on dark and stormy nights, in which they often suffered severe hardships.”3

One trip led to the unraveling of Chaloner’s spy ring. After carrying another group of Loyalists on a “stormy night” to the safety of the Rose, Crossing and the black man “went to the fireplace as usual to warm and dry themselves” on board Wallace’s frigate. Earlier in the day, Wallace had captured a merchant vessel, and one of the men detained from it was then “by the fire and…knew Crossing.” A few days later, after an unsuspecting Wallace released the man, he immediately notified Whig authorities of Crossing’s being on board Wallace’s ship. “Crossing, without suspicion of danger, was soon taken and strongly guarded” in a Newport jail.

The Sons of Liberty then became “wholly fixed” on Chaloner, knowing of his close relationship with Crossing. Chaloner further felt “extreme danger” from “the panic of the black for fear of being charged with being on board” the Rose. After calming the black man down, within several days, the enterprising Crossing escaped from his prison and found a place to hide. Patriot authorities twice searched Chaloner’s home and placed “guards and sentinels…in all parts of the town to prevent” Crossing from escaping to one of Wallace’s ships. Chaloner eventually discovered Crossing’s hiding place (with the assistance of a second black man), but with all the boats in town secured by the guards each night, they could not find a way to get to a British warship anchored in Narragansett Bay.

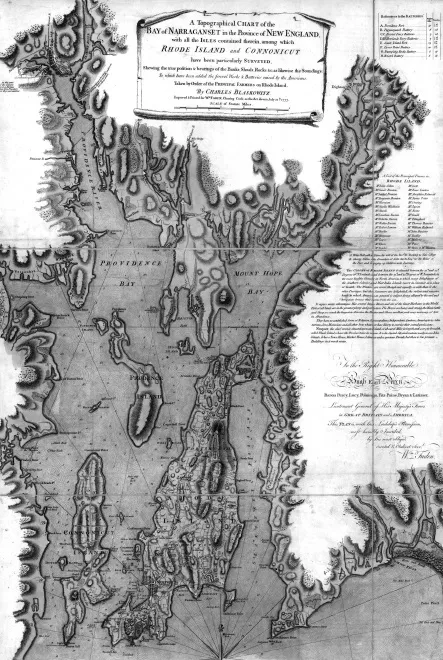

A Topographical Chart of the Bay of Narragansett by Charles Blaskowitz, London, 1777. Library of Congress.

The British frigate Rose took on board escaped Loyalists as well as spies. Image of operational copy of the ship from John Fitzhugh Millar.

Chaloner came up with an idea to escape from Newport. He found “a very long and wide plank” of wood that “was deemed sufficient to support his weight.” Chaloner then took it into the shop of a local carpenter, whom Chaloner knew to be “a zealous friend” to the Crown. The former sheriff paid the carpenter to build a seat on the plank and have it ready for him at a moment’s notice. Finally, one dark night when the wind was not too strong, Chaloner made his escape attempt. He had to paddle to the Glasgow, then two miles away. During the perilous journey, he “experienced very great danger and fatigue” and choppy water “overset his plank several times.” Being “very strong” and determined not to die, after “several hours hard labor,” he finally reached and boarded the Glasgow. Chaloner did not say what happened to Crossing or his black assistant, though it is known that Crossing later worked with Chaloner for the British army during its occupation of Newport.

MARY WENWOOD MISTAKENLY TRUSTS HER FORMER HUSBAND

Perhaps the most infamous American spy to be detected, prior to Benedict Arnold, was traced and exposed due to the role of a Newport woman. Her name was Mary Wenwood, formerly Mary Butler, someone that Reverend Ezra Stiles of Newport’s First Congregationalist Church referred to as “a girl of pleasure.”4 In July 1775, Wenwood travelled from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to ask her former husband, Godfrey Wenwood, who kept a bakery at Banister’s wharf in Newport, to deliver a letter to Captain James Wallace of the Rose. If that were not possible, he was to deliver it to Charles Dudley, the Newport customs collector, or to George Rome, a renowned Loyalist then residing in Newport. Either of them, in turn, could make sure the letter reached Wallace, who could see it delivered to British authorities in occupied Boston.

Mary thought her divorced husband was a Loyalist and that she could trust him. In fact, he was contemplating marrying another local woman and recognized immediately the risk involved in delivering correspondence to Wallace, Dudley or Rome. He agreed to the task, but never completed it. Instead, he took the letter to his friend, Adam Maxwell, who ran a school in the front room of the nearby Brick Market. Together, they opened the letter, but were unable to read it because it was in code. At some point, Maxwell asked Reverend Stiles, a staunch Patriot, if he knew how to decipher characters, but apparently they never showed the minister the letter.5

Two months later, Godfrey Wenwood received a letter from his now-anxious ex-wife, who wondered why her “sister” had never received the letter. She wanted to know if Godfrey had sent it and whether “you ever got an answer from my sister.”6

Godfrey immediately became apprehensive. Only a British supporter could have known that the letter had not reached British-held Boston. Further, the letter’s author was likely an enemy to the Whig cause. He and Maxwell therefore travelled to Providence and showed the letter to Henry Ward, secretary of state in Rhode Island’s Whig-controlled government. Ward sent the men on to Brigadier General Nathanael Greene, commander of the Rhode Island contingent of the Continental army then surrounding Boston. In his letter of introduction for the men, Ward advised Greene that “the strictest inquiry ought to be made.”7 After meeting with Wenwood and Maxwell in late September, Greene promptly forwarded both letters to the commander in chief of the Continental army, General Washington.

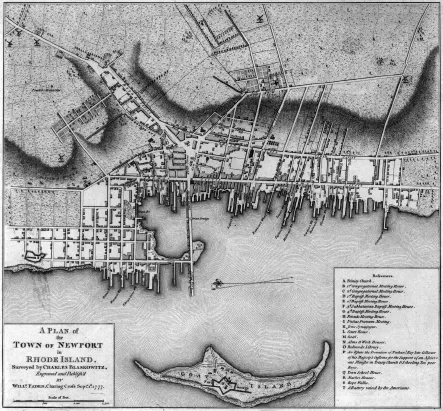

A Plan of the Town of Newport in Rhode Island, surveyed by Charles Blaskowitz, London, 1777. Library of Congress.

Greene’s expedience paid off. “Realizing that the ciphered letter probably contained military intelligence and that a spy was most assuredly in their midst,” wrote John Nagy in his recent, authoritative book, Dr. Benjamin Church, Spy, “Washington acted quickly. He sent Wenwood to meet with the woman (his ex-wife) to use the confidence she had in him to find out who had given her the letter. But she was not so easily fooled, and Wenwood’s efforts were unsuccessful.” Washington then ordered Mary Wenwood to headquarters. After being “terrified by the threats of severe punishment,” she finally revealed that the author of the ciphered letter was Dr. Benjamin Church.8

The revelation shocked Patriots. Dr. Church was the grandson of a Little Compton native of the same name, a famous Indian fighter whose company had killed King Philip in 1676. Dr. Church was then serving as the surgeon general of the Continental army and, in that role, frequently met with General Washington. He was a sitting member of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and, as a member of the Sons of Liberty, had worked closely with Whig leaders such as John and Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

Once the Americans deciphered the code used in his letter (according to Nagy, the code was not difficult to crack), Church’s roles as a spy and traitor were confirmed. The letter, which Church had written in his Cambridge residence, was intended for Major Edward Crane of the British Forty-Third Regiment, then in Boston. It disclosed the strength of the Continental army, the state of its supplies and gunpowder and the number of artillery pieces the Americans had. Church also passed on prophetic advice for General Thomas Gage, the commander of British forces in Boston: “A view to independence grows more and more general. Should Britain declare war against the Colonies, they are lost forever.” He concluded his letter with a request for Major Crane “to write me largely in cipher, by the way of Newport, addressed to Thomas Richards, merchant.”9 Church was arrested, jailed on orders of the Continental Congress and tried for and convicted of treason.10 After spending about a year in jail, he was permitted to depart on a schooner for the Carribean. Neither ship nor doctor was ever heard from again.

It turned out that Mary Wenwood was Church’s pregnant mistress. Unfortunately for Church, who had been increasing his coffers with payments from his British spymasters in Boston, she made the crucial mistake of trusting that her former husband would not betray her.

![]()

2

The British Occupy Newport and the Rest of Aquidneck Island

December 1776 to August 1777

THE BRITISH INVADE—THE FIRST SPIES

On December 8, 1776, Lieutenant General Henry Clinton and 7,100 British, Hessian and Tory troops, on board a fleet of seventy-one warships and transport vessels, seized Newport, Rhode Island, and the rest of Aquidneck Island. Patriot troops, no match for this overwhelming ground and sea force, evacuated the island, allowing Clinton’s troops to land without resistance.

In short order, British forces occupied all of Aquidneck Island, just fourteen miles long and two miles wide, and small Conanicut Island, opposite Newport Harbor. His job quickly and easily completed, Clinton departed, leaving command of the British garrison to Lieutenant General Hugh Earl Percy. Percy’s second in command was Major General Richard Prescott.

Commodore Sir Peter Parker, commanding British naval forces at Newport, immediately stationed frigates in the three entrances to Narragansett Bay, thus keeping privateers and commercial vessels from coming in and out of the bay. “I am very much pleased with the good news you have sent unto me, which secures an excellent port for the ships,” King George III wrote to the Earl of Sandwich.11

Still, the British only occupied about one-quarter of Rhode Island. The rest of the state—and neighboring Bristol, Dartmouth and Plymouth Counties in Massachusetts—were firmly in the Whig camp. This was confirmed by a Loyalist spy, who informed General Percy that in Providence, “the inhabitants are notorious rebels, scarcely a loyal subject to be found.” East of Narragansett Bay, the spy found Bristol’s inhabitants were “disloyal.” In Taunton, Massachusetts, “a fine village,” the inhabitants were all “rebels, except a few at Swansea called Quakers.” It was the same throughout the rest of southeastern New England.12

British warships in Narragansett Bay. They dispatched small boats filled with soldiers ready to...