![]()

WHAT'S A CHICANO? DEPENDS.

NO ONE EVER OWNED EXISTENTIALISM. IT HAS ALWAYS MEANT DIFFERENT THINGS TO DIFFERENT PEOPLE. IT WAS NEVER A SINGLE DOCTRINE THAT WAS LAID DOWN DEFINITIVELY BY ONE PERSON OR GROUP. EACH PIECE OF WRITING ABOUT IT IS DIFFERENT, EACH BEARS AN INDIVIDUAL STAMP. THERE WAS NO SINGLE VOICE OF AUTHORITY, SO ITS DEFINITION HAS ALWAYS HAD BLURRY EDGES. . . . IT COULD BE SEEN AS A HISTORICAL NECESSITY OR INEVITABILITY, AN EFFORT TO ADAPT TO A NEW CONFLUENCE OF CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL FORCES.

DAVID COGSWELL, EXISTENTIALISM FOR BEGINNERS

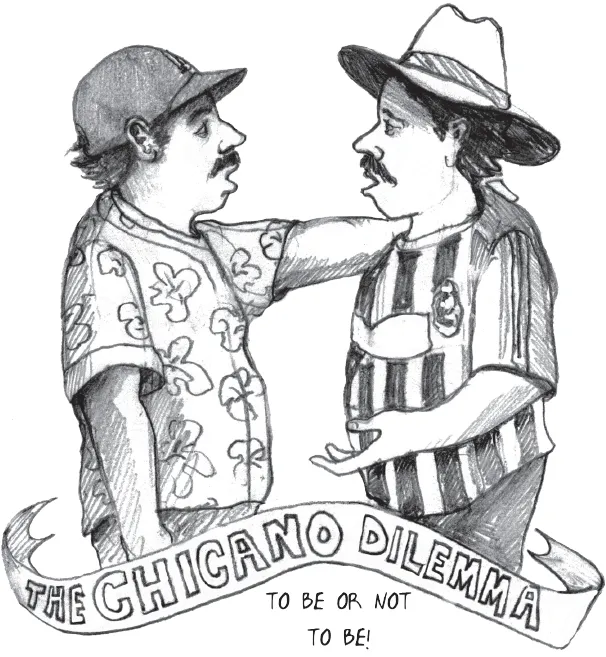

Odd as this may seem, if you remove “existentialism” from the above quote and replace it with “Chicano” you get a pretty good understanding of the term and its complicated place in Mexican American history. Armando Rendón, in his landmark 1970 book, Chicano Manifesto, wrote, “I am Chicano. What it means to me may be different than what it means to you.” More than two decades later, the Chicano poet and novelist Benjamin Alire Sáenz wrote, “There is no such thing as the Chicano voice: there are only Chicano and Chicana voices.” To this day, the term “Chicano” maintains its blurry edges, but it continues to reflect a meaningful way of thinking about the confluence of cultural and historical forces—in short, about life.

Many activists in the Chicano Movement pointed to an etymology of the word “Chicano” rooted in the clash between Spain and Mesoamerica, specifically the Spanish conquest of the Valle de Mexica and its people, the Mexicas (more commonly known as the Aztecs), in the 16th century. Mexica was pronounced Meshica, but lacking a letter equivalent, the Spaniards changed the “sh” to an “x”—hence Mexica, or México, or Mexicanos. Shicano was simply short for Meshicanos. For these early activists, then, the term Chicano served two purposes: it made a connection not only to their Mexican roots, but also to their indigenous past. Compare that to the term “Hispanic,” which many Chicanos rejected because it references only the connection to Spain, basically negating half an identity and history.

Historically, however, most Mexican Americans knew the word Chicano through its common usage, mainly as a derogatory label for Mexicans who had become “gringofied,” linguistically and culturally, when they immigrated to the United States. Pocho, literally meaning rotten fruit, was another common label. These terms indicated a people stuck in between, who were neither American nor Mexican, who could speak neither proper English nor proper Spanish, who had forgotten their Mexican culture as they adopted the values and attitudes of North American society—in essence, a lost people. Never to be truly American, lapsed as Mexicans, they were a people without a country.

But Mexican Americans also used the term Chicano to describe themselves, and usually in a lighthearted way, or as a term of endearment, maybe even as self-effacement. Doing so expressed awareness that they had not just departed from or forgotten their Mexican origins, but that they had actually become a unique community. When Mexican Americans began identifying as Chicanos, it was a form of self-affirmation; it reflected the consciousness that their experience living in between nations, histories, cultures, and languages was uniquely and wholly theirs. This is what gave birth to a sense of community, a people: los Chicanos.

Lastly, and maybe most importantly, civil rights activists who called themselves Chicanos emphasized the fact that it was a name not given to them or placed on them by an outsider, but a name that they had chosen themselves. That choice reflected the Movimiento's greater goal of self-determination, standing up against and rejecting the Mexican American community's long-suffering history of racism, discrimination, disenfranchisement, and economic exploitation in the United States (more on that soon).

DINNER PARTY FOR EL MOVIMIENTO

Let's say this is not a book but a dinner party where you invite all the key figures from the Chicano Movement to discuss their role in this tumultuous period. Unfortunately, the evening would already be off to a bad start. Why? Well, you couldn't possibly invite everyone, but you'd be expected to. One of the main currents of the Movimiento was to bring attention to all the struggles of the Mexican American community—whether those of a soldier in the Vietnam War, a field-worker in California, or a university student—and seeing them as one. And what is a dinner party if not an affair that includes a chosen few and excludes others?

But we get past that. Your dinner party must proceed, space is limited, and a guest list is in order. You definitely want to invite César Chávez, a national hero on par with other inspirational leaders whose faces have graced the cover of Time magazine, stamps, and countless posters in grade-school classrooms. Dinner with César alone would be intimidating, so you attempt to balance his saintly demeanor with that of his sister in nonviolence, the rabble-rouser Dolores Huerta.

The duo is first to arrive, and your dinner party and history lesson are solidly underway. Dolores leads the conversation, and soon you have a thorough understanding of the United Farm Workers (UFW) and their struggle against powerful and exploitative California growers. But you're surprised to learn that César never considered himself a Chicano leader; nor did most of his fellow farmworkers consider themselves Chicanos. But before you can ask him to explain, in walks a man who effusively announces that he is the cricket in the lion's ear, none other than Reies López Tijerina from New Mexico.

In the manner of a soapbox preacher, Reies launches into a long discourse on his efforts to reclaim the lands stripped away from the Indo-Hispano people of New Mexico following the Mexican-American War and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (which granted the United States about half of Mexico's territory). Reies recounts in vivid detail his persecution at the hands of New Mexican authorities, but after a half-hour and no signs of stopping, you begin to worry that no one else will be able to get a word in edgewise. Reies is in the middle of his story about the ill-fated Tierra Amarilla courthouse raid of 1967 when he is interrupted by the arrival of Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez, who, by way of introduction, begins reciting his epic poem of Chicano identity, I am Joaquín.

When Corky finishes his fiery recitation, he announces, much to your consternation, that participants of the Chicano National Youth and Liberation Conference have followed him all the way from Denver, Colorado. As if on cue, in walks a group of boisterous young people, many of them with long hair and wearing ponchos and overalls. They quiet down only when you answer their calls for pens and paper so they can work on updating the goals of their so-called “spiritual plan.”

Just as you're about to make your way back to the dinner table, a young man introducing himself as José Angel Gutiérrez walks through the door accompanied by yet another large group, this one hailing from Crystal City, Texas. Carrying lawn signs and campaign buttons, they identify themselves as members of La Raza Unida Party. When you explain that there are not enough seats at the table, they make their way to the living room, where they find a telephone (the old rotary kind) and take turns calling potential voters.

With all the hubbub, you almost miss the arrival of a quiet, distinguished-looking man, a little older than most in attendance, who appears out of place. He introduces himself as the Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar. But before you can show him to the table, the front door opens and in walks a cadre of stern-faced young men and women, all dressed in khaki and brown. They stand at attention like soldiers in formation and bark out that they are the Brown Berets, defenders of the Chicano barrio.

The house is ready to burst, and you cringe as more commotion outside draws you to the window. You hear chants.

“What's going on?” you ask, afraid to open the door.

A participant of the youth conference informs you that the Chicana Caucus has organized a protest against your dinner party on account of the fact that so few women were invited. Soon the protesters make their way inside, and between their chants decrying patriarchy and demanding that their voices be heard, Corky reciting his poem again (upon request), the youth reading one platform after another, the pollsters making phone calls, and the general din of one explanation after another of this and that event, you can hardly hear yourself think. At wit's end, you cry out that what you wanted was a quiet little dinner party for the leaders and luminaries of the Chicano Movement to fill you in on the important events and ideas, that invitations had been sent out, and that the invitations did not say “plus one” or “plus two” and certainly not “plus fifty” and that you'd appreciate if everyone left at once.

Suddenly there is silence. Someone, you don't know who, says that if quiet is what you wanted then you've missed the point of a movement. You are unswayed. Guests, both invited and uninvited, begin to file out. You avoid César Chávez's eyes. When everyone has departed, you begin putting the house back together. Just as you're finally catching your breath, you're startled to hear the front door swing open.

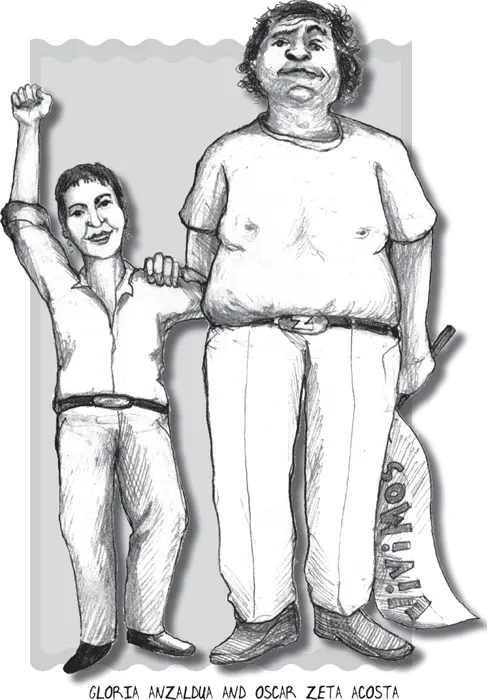

In stomps a giant man with bulging, manic eyes, immediately demanding to know where the liquor cabinet is located. He introduces himself as the Brown Buffalo. He assumes you've heard of him, and when you tell him you haven't, he declares that he's the most radical of radical Chicano lawyers, Oscar Zeta Acosta. He locates the liquor, pours himself a glass, and sits at the table. “Wasn't there supposed to be dinner?” he asks.

After loading his plate full of food, the Brown Buffalo, as he insists on being called, offers his version of the Chicano Movement, starting with his childhood. As he recounts his hang-ups about race and his forever frustrated quest to fit the American ideal or achieve the American dream, it dawns on you that Oscar's version of the Chicano Movement never deviates from his own point of view as the central protagonist. He grows angry, he sheds tears, he reveals details that make you uncomfortable, and just when you think he'll never stop, he passes out after one too many drinks.

As you clear the table, you hope you've seen the last of it all. But soon you hear a gentle knock at the door. With trepidation you open it, half expecting to find an even larger Brown Buffalo. Instead, you find a small woman with short hair and a kind smile. “I'm sorry I'm late,” she says. “My name is Gloria Anzaldúa.” You invite the Chicana s...