![]() I Visions of Health

I Visions of Health![]()

Chapter 1

Soundness

I am infirm and burdened with the influence of slavery, whose impress will ever remain on my mind and body.

— Mattie J. Jackson, The Story of Mattie J. Jackson, 1866

The up-country planter’s wealth consists chiefly in his negroes, and in proportion to their thrift and healthiness, just in such ratio does he prosper. The principal value of the negro with us is his increase, consequently [slave health] addresses itself to the interest as well as the humanity of the slave-holder.

— W. Fletcher Homes, M.D., Charleston Medical Journal and Review, 1852

“The being of slavery, its soul and body, lives and moves in the chattel principle,” wrote Presbyterian minister James W. C. Pennington in 1849. A fugitive from slavery and an active abolitionist, Pennington insisted that “kind and Christian masters” could never ameliorate the injustice of slavery. Without the destruction of the detested “bill of sale principle,” warned Pennington, even persons enslaved in relatively milder conditions could at any moment face “the cart-whip, starvation, and nakedness.”1 The principle of human property, as James Pennington well knew, permeated southern society, extending not least of all to slave health. In southern fields, auction yards, and plantation sickhouses enslaved men and women confronted a political economy that cast the shadow of the marketplace over the most intimate events of birth, sickness, and death. While abolitionists and proslavery advocates argued over the moral fate of a society that held human beings as property, the system of slavery daily and concretely continued to mark African American lives and bodies.

Historians have for some time debated the influence of the property principle on the health of slaves. The topic of slave health, Todd Savitt notes, has served many historians as a barometer for the “benignity or harshness of ‘the peculiar institution.’”2 In the early twentieth century, historians U. B. Phillips and Carter G. Woodson disagreed markedly over whether slaveholders were generally “solicitous” or neglectful of slave health. Since that time some scholars have argued that economic interest motivated planters to provide a relatively high level of health care to their enslaved laborers. Others have disagreed, observing that property interest no more protected slaves against abuse than it did the land, tools, and livestock of the slaveholder.3 Yet the debate over plantation health conditions, for the most part, casts slave health care as a problem only for slaveholders. It treats the property principle as a force that either did or did not motivate slaveholders to provide health care for their enslaved laborers. Missing from either side of the debate is any sustained discussion of how enslaved African Americans themselves understood the chattel principle and slaveholders’ interests.

How did enslaved women and men analyze slave ownership and its impact on plantation health and healing? Approaching the history of plantation health from this perspective quickly brings into focus a struggle to define the very meaning of health and the terms of healing. This struggle gave rise to two competing visions of health and healing. The medicine of white slaveholders, on one hand, was deeply implicated in southern legal and economic institutions, which translated slave health into slave-holder wealth. In contrast, enslaved African Americans developed a powerful countervision of personal and collective endurance and, when possible, transcendence. The stories, songs, and testimony of enslaved African Americans reflect a shrewd critique of the influence of the property principle on slave health within the plantation economy.

The fusion of southern health and property concerns had immediate and life-changing consequences for an enslaved but defiant man named Harry living in South Carolina’s Lowcountry. Less than a year before John Brown led the raid on Harpers Ferry, Harry struck his own blow against slavery. On a December Monday in 1858, physician John A. Warren of Colleton District wrote an urgent letter to his cousin John D. Warren, who was also Harry’s legal owner. John A. complained that Harry had set fire to a rotting sill under the portico of the house that morning. He believed that Harry acted in collusion with another man, Jeffry, a runaway who had tried before “to burn me and my Family up.” The fire was quickly contained, but it scarcely set John A. at ease. “I will be compelled to have an armed Guard at all times,” he complained, “until the old demon can be caught & sent to Jail for I swear I would not have such a wretch about me for the world.”4

Harry had distinguished himself as a threat to the Warrens long before the morning of the fire. John A. identified Harry as “July’s son, chip of [sic] the old block,” perhaps indicating a family tradition of resistance. Some time earlier Harry had started another fire inside a table drawer in the Warren home. In 1857 he had been confined in the Charleston Work House, where he received one “correction,” charged to John D. Warren’s account for $1.50. Harry might also have had a history of escape that led to his incarceration, as the workhouse bill itemized four “Advertisements,” which were often used to indicate the capture of a runaway slave or to advertise the inmate for sale. Now, with past trouble culminating in arson and conspiracy, John A. Warren vowed that “such an act must be crushed and the actors made an example of.”5

John D. quickly made plans to ship Harry to Charleston for immediate sale, but Harry was determined not to be sold off so easily. Within a fortnight the Charleston slave merchant and auctioneer establishment of Capers and Heyward indicated it would be sending for Harry at Walter-boro the following week.6 Although exact events are not recorded, Harry most likely attempted an escape that led to violent confrontation. By early February Harry had been jailed in Walterboro, “shot with small shot” in his back. A search of his baggage revealed a pistol and ammunition, although it is unclear whether he had had an opportunity to use them.7

Harry’s rebellious acts and subsequent injuries brought his status as chattel sharply into view. In the early days after his capture Harry was feverish, hemorrhaging, and coughing blood. For the next month his medical condition became the subject of frequent correspondence between the Warren cousins and Charleston physician Charles Pinckney. Their primary concerns were whether and when Harry would recover enough to be sold at the high prices of the booming 1850s slave market. When Pinckney visited Harry the following week, the physician reported hopefully that the sale would not long be delayed. “He is still improving and will soon be ready for your purposes,” Pinckney wrote to John D. Warren.8

During this early period of convalescence John D. Warren sent an enslaved woman named Judy to nurse Harry in jail. In delegating Harry’s round-the-clock care to Judy, Warren simply transferred a familiar pattern of slave women’s health work from the plantation to the jailhouse. Enslaved women commonly served the daily health needs of the slave quarters, yet Judy had been sent to the isolation of a Charleston jail specifically to restore Harry’s body for the market. Her relationship to Harry was unclear, but her objection to her assignment was unmistakable. Within days Pinckney sent Judy back to Warren’s household, commenting that Judy “had great scruples about being in jail under any circumstances.”9

As the immediate danger to Harry’s life subsided, Harry’s captors raised a new concern. John A. Warren warned his cousin that scar tissue around the wounds might in time irritate and inflame the lungs. If Harry had a “predisposition to Consumption,” he warned, the irritation might eventually “excite that disease.” For the present, however, the physicians decided they had nothing to fear. To support this contention they noted with satisfaction that Harry had not “lost any flesh” from his ordeal.10

Despite the doctors’ optimism, Harry’s wounds continued to present a barrier to his sale. The auctioneers, Thomas Capers and T. Savage Heyward, indicated in March 1859 that they had lodged Harry at the workhouse (where he had previously been incarcerated and whipped) but as yet had received no offer for him. “The objection is the marks of the shot in his back,” they explained. “His teeth are also slightly defective. We hope to sell him soon but will not we fear get $1700.”11 Capers and Heyward’s prediction proved true. On 23 March the slave traders sold Harry at a private sale on the Charleston docks “with distinct understanding that he be removed from and beyond the limits of the State [of] So Ca.” John D. Warren received $1,100, the designated value of Harry’s scarred and “defective” body.12 Harry’s harsh passage through the hands of slaveholders, physicians, and auctioneers vividly illustrated the dynamics of white southern medicine practiced in the interest of the planter class.

White Perceptions of Slave Health as Soundness

With the commodification of black bodies came the objectification of African American health. The intersection of medicine with the southern political economy produced a narrow definition of slave health permeated by concerns of slaveholder status and wealth. Questions concerning slaves’ mental and physical health influenced the very nature of economic transactions in slave property. In turn, the principle of human property profoundly shaped the practice and theory of southern white medicine. Even the more mundane aspects of plantation health, such as the care of injuries and illnesses, reflected the fact that human property constituted the central form of southern wealth.13 The Warrens’ concern for Harry’s health and sale value thus emerged from a context not peculiar to Harry alone. Although Harry’s arson and rebellion may have been memorable events, both John A. Warren and his cousin routinely acted on matters of slave health as part of the daily business of running their plantations. In a thousand daily interactions the marriage of professional medicine and slavery put a price on black health. It shaped the terms of the medical attention slaveholders directed at enslaved men and women and deployed medical knowledge not only to heal but to preserve the status quo in a slave society.

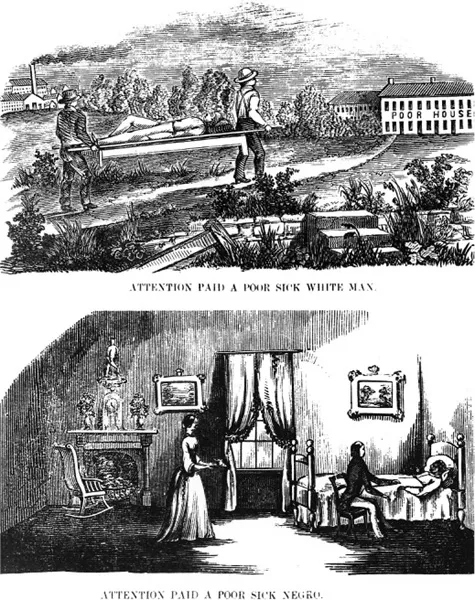

Attention Paid a Poor Sick White Man and Attention Paid a Poor Sick Negro. This illustration from an antebellum proslavery treatise contrasts the slaveholder’s superior care of enslaved laborers against the callousness of northern wage labor. Solicitous whites administer to a sick slave in the spacious comfort of the planter’s house. The actual conditions of slave health care were far different from the scene depicted. (Josiah Priest, Bible Defence of Slavery [1853])

The vision of slave health embraced widely by slaveholders and white medical professionals crystallized in the concept of “soundness.” In 1858 Juriah Harriss, a physician and medical professor at the Savannah Medical College, deemed the evaluation of slave soundness “a question of great import to the southern physician and slave owner.”14 Frequently employed in both slave sales and medical jurisprudence, the term indicated an enslaved person’s overall state of health and, by extension, his or her worth in the marketplace.15 Harriss’s lengthy discussion revealed the legal complexities of the concept of soundness. Soundness in its most basic sense concerned the health of a slave, measured in his or her capacity to labor, at the time of sale. Yet the definition of soundness included not only the present health of the individual but past and future health as well. In Harry’s case, for example, John A. Warren worried that Harry’s shotgun wounds would later dispose him toward consumption.16 Soundness in enslaved women also described their future capacity to bear children. Juriah Harriss operated on an enslaved woman to remove a large tu...