eBook - ePub

From Chicaza to Chickasaw

The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715

Robbie Ethridge

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 360 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

From Chicaza to Chickasaw

The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715

Robbie Ethridge

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

In this sweeping regional history, anthropologist Robbie Ethridge traces the metamorphosis of the Native South from first contact in 1540 to the dawn of the eighteenth century, when indigenous people no longer lived in a purely Indian world but rather on the edge of an expanding European empire. Using a framework that Ethridge calls the "Mississippian shatter zone" to explicate these tumultuous times, From Chicaza to Chickasaw examines the European invasion, the collapse of the precontact Mississippian world, and the restructuring of discrete chiefdoms into coalescent Native societies in a colonial world. The story of one group--the Chickasaws--is closely followed through this period.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

From Chicaza to Chickasaw è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a From Chicaza to Chickasaw di Robbie Ethridge in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Sciences sociales e Études amérindiennes. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

Sciences socialesCategoria

Études amérindiennesChapter 1 Chicaza and the Mississippian World, ca. 1540–1541

On Tuesday, December 14, 1540, Indian warriors gathered on the bluffs looking down on the river of Chicaza. There, they awaited the arrival of the warriors of a powerful and threatening foreigner. Their own principal leader had heard about a foreign lord who was en route to his province, Chicaza. He had other intelligence about these foreigners, too. He knew that the foreign force had come close to defeat at the town of Mabila in a surprise attack led by the powerful lord Tascalusa only a few months earlier. He knew that they had strange, big deer that the men rode, making them formidable in battle. He knew that their mico(chief) demanded respect and tribute from whomever he encountered. He knew that they carried knives, arrow points, and other implements made out of a metal much harder than copper. And although etiquette would require him to act with diplomatic protocol if they met, the leader knew that this new lord did not come in peace. So, upon receiving news of the foreigners’ approach to the river of Chicaza, which constituted the eastern boundary of his polity, the leader met with his council, military officers, and war captain to debate and decide on a course of action. They opted to meet the foreigners where the road they were following crossed the river into Chicaza; there, they would make a stand to prevent the foreigners from marching into their province.

The river of Chicaza is known today as the Tombigbee River, and the confrontation between the Indians of Chicaza and the army of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto likely took place around present-day Columbus, Mississippi.1 Parts of the above scenario are, of course, highly inferential. The chronicles of the Soto expedition describe the two opposing armies facing off at the border of Chicaza, but what the warriors of Chicaza knew about Soto and his army prior to this event was not recorded. The chroniclers, however, do tell us that Indian men were at the bluffs when the Spaniards arrived and that they threatened that if the Spaniards were to attempt a crossing, they would be met with force. We also know that Chicaza's warriors were armed and alert, and they planted many war banners on the bluffs, signaling to the offending army their intentions. The standoff lasted three days.

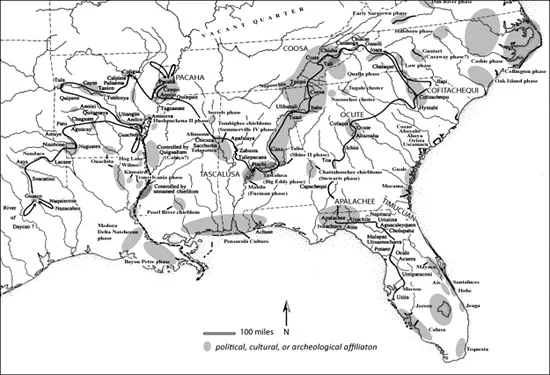

This encounter came in the second year of Hernando de Soto's expedition of conquest and “discovery” through much of the American South. Soto and his army were one of the first—and one of the last—European expeditions to witness the Mississippian world of Native southerners (Map 1).2 The next Europeans into the interior South came over 100 years later, and what they saw was a world in the process of collapsing and restructuring. Therefore, we begin this history at the time of the first encounters between the people of Chicaza and Europeans. In so doing, we set a benchmark by which we can evaluate and delineate the many changes that took place once the Mississippian world began to falter and finally fall. It also provides a benchmark by which we can more clearly understand the restructuring that occurred after the fall.

“Mississippian” is the name archaeologists use to designate the time period between roughly 900 C.E. and 1700 C.E., during which southern peoples organized themselves into a particular kind of political organization termed “chiefdom.”3 “Mississippian world” refers to the fact that none of these chiefdoms existed in isolation. Although the Mississippian milieu was often one of much political strife and conflict, the chiefdoms were tied together in myriad ways, such as through trade, travel, information, marriage ties, and exchange of war captives.

Although it was not the only form of political organization extant in the Mississippian world, the chiefdom was the dominant political type. A chiefdom is a political order with basically two social ranks determined by kinship affiliations: ruling elite lineages and nonelite lineages. Generally speaking, the members of the chiefly lineage were considered related to supernatural beings, which gave them religious sanction for their status, prestige, and political

MAP 1 The Mississippian World, ca. 1540, Showing the Route of Hernando de Soto (Note: the gray areas represent known political and social affiliations or known archaeological phases; town names appear in their approximate locations. Adapted from Charles Hudson, “The Hernando de Soto Expedition, 1539–1543,” 1996. Courtesy of Charles Hudson.)

FIGURE 1 Moundville as it may have appeared in the thirteenth century (From Vincas P. Steponaitis and Vernon J. Knight Jr., “Moundville Art in Historical and Social Context,” in Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South, edited by Richard F. Townsend and Robert V. Sharp, 168 [Figure 3]. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press for the Art Institute of Chicago, 2004. © 2004 Steven Patricia. Reproduced with permission of Steven Patricia and the Art Institute of Chicago.)

authority. The political and religious center of a chiefdom was a large town with an earthen temple mound fronted by a large plaza and often surrounded by other mounds (Figure 1). Neighborhoods of the common people typically surrounded the town center. The mico lived atop the temple mound, while lesser people of the chiefly lineage resided on the smaller mounds 4

Archaeologists are uncertain about the extent and nature of a mico's power. They generally agree that the chiefly elite constituted a centralized political body and that those members held permanent inherited offices of high rank and authority, with the mico holding the highest office. The mico had the authority to settle disputes, punish wrongdoers, make judgments, and command tribute, usually in the form of surplus production and labor. But it appears that an elite's consolidation of power varied from one chiefdom to another. In some cases, the mico held coercive if not autocratic power and consulted only with others of the elite lineage; but in other cases, the mico exerted influence and authority but not real power, and he or she deliberated with local town councils in addition to the elite lineage when making decisions.5

Commoners lived in neighborhoods situated around the mounds and public plaza and also in farming villages strung up and down a river valley that constituted the heart of a chiefdom's territory. These farming villages provided the foundation of the Mississippian economy, which was based on intensive corn agriculture. The common folks farmed, fished, hunted, and gathered wild plant stuffs for food and other materials necessary for daily life. In addition, the chiefly elite sponsored traders who maintained far-flung trade networks through which they exchanged goods such as copper, shell, mica, high-grade stones like flint, and other materials, which were then fashioned by elite-sponsored artisans into emblems of power, prestige, and religious authority.

A chiefdom was largely self-sufficient economically, in that the people could feed, house, cloth, and defend themselves using resources available within their boundaries. The exceptions to this were salt and hoes made out of particularly good stone. These items were necessary to daily life, and they were found in only a few places and then traded throughout the South. Likewise, prestige goods made out of hard-to-get materials such as shell and fine stone circulated widely. Although the circulation of salt, hoes, and prestige goods was a vital part of the Mississippian world, it is unlikely that their exchanges served to integrate the Mississippian chiefdoms into a single, unified economic system.6 Within the chiefdom, the economy was one of household or community-level self-sufficiency; people made their living from farming, hunting, gathering of wild plant foods, and using local resources such as wood, cane, and other raw materials for buildings and clothing. And although these communities were often engaged in trade, they were not dependent on it.

In the more autocratic polities, the chiefly elites were exempt from mundane activities such as farming, and they received tribute from the citizens in the form of foodstuffs, exotic goods, animal skins, stone, and other raw and finished materials. In the less-centralized chiefdoms, elites probably engaged in subsistence activities such as farming and hunting, but they still received tribute from the nonelites. In both cases, the mico used tribute goods for themselves and their families as well as to mediate arguments, garner allies, give succor to villages who found themselves low on resources, and otherwise maintain control and order over the towns and villages in the chiefdom.

The elite had obligations to the rank and file. In addition to providing resources in times of need, the mico and his or her kin also mediated conflicts, oversaw the building and maintenance of public works such as the mounds and plaza, kept the religious and ceremonial calendar and performances, supplicated the deities, and provided protection for the citizenry against foreign attacks. In fact, war iconography is prevalent on much Mississippian artwork, indicating that warfare was important and imbued all aspects of daily life. The palisaded towns that typically lay on a chiefdom's borders and the large buffer zones, or uninhabited regions between chiefdoms, indicate that warfare was not just important but probably endemic 7

Archaeologists divide the Mississippi Period into Early Mississippi (900-1200 C.E.), Middle Mississippi (1200-1500 C.E.), and Late Mississippi (1500-1700 C.E.). Soto's entrada occurred during the Late Mississippi Period. If the Spaniards had come 300 years earlier and had traveled toward present-day St. Louis, Missouri, they would have seen Cahokia, the earliest and largest of all Mississippian polities, which was occupied during the Early Mississippi Period. At its height, around 1050–1200 C.E., Cahokia proper was an expansive center that covered six square miles, with a population of around 20,000 and over 100 mounds of various sizes. Cahokia's influence dominated the Early Mississippian landscape. And by the Middle Mississippi Period, the Mississippian way of life was firmly in place across most of the South. 8

The most famous Middle Mississippian sites are Moundville and Etowah in western Alabama and northwestern Georgia, respectively, but there are also impressive Middle Mississippian mound complexes throughout the central Mississippi River valley, the lower Ohio River valley, and most of the mid-South area, including western and central Kentucky, western Tennessee, and northern Alabama and Mississippi. This appears to have been the core of the classic Mississippian area, although other chiefdoms of various sizes existed on the margins, such as the famous Spiro site in present-day Oklahoma.

Chiefdoms were not uniformly alike across space and time. Clearly nothing ever matched the size of Cahokia, although archaeologists understand the classic Middle Mississippian chiefdoms such as Moundville to have been quite large, complex chiefdoms. A “complex chiefdom” was a political organization in which one large chiefdom exercised some sort of control or influence over smaller chiefdoms within a defined area. Archaeologists call the smaller chiefdoms “simple chiefdoms” because they were polities in which the elite only controlled the towns connected to that chiefdom. Simple chiefdoms were clusters of about four to seven towns, with one of these usually having only a single mound and serving as the center of the chiefdom. These towns were small, with an average population of 350 to 650 people, and a simple chiefdom, as a whole, had an average population of between 2,800 to 5,400 people. The average diameter of a simple chiefdom was about 20 kilometers (12.43 miles), while the average distance between simple chiefdoms was 30 kilometers (18.64 miles).9

In the Late Mississippi Period, complex and simple chiefdoms existed side by side, and in a few cases single, especially charismatic leaders forged an alliance of several complex and simple chiefdoms into “paramount chiefdoms.” Archaeologists are not in agreement as to the specific organizational mechanisms that held a paramount chiefdom together. According to anthropologist Charles Hudson, whereas one can think of a simple chiefdom as a “hands-on, workaday administrative unit under the aegis of a particular chief, the paramount chiefdom may have been little more than a kind of non-aggression pact, and the power of a paramount chief may have been little more than that of first among equals.” In other words, paramount chiefdoms were political entities that could have ranged from strongly to weakly integrated, and paramount chiefs could have possessed power or merely influence. The concept of the paramount chiefdom, then, implies a less-centralized administration than larger, statelike organizations but a larger area of geographic influence than that of simple or even complex chiefdoms, sometimes spanning several hundred miles. 10

Mounting archaeological evidence indicates the occurrence of a pattern of “cycling” in complex and simple chiefdoms—a seemingly endemic rise and fall of chiefdoms through time. For example, in the Savannah River area in present-day Georgia and South Carolina, there were a number of chiefdoms that rose and fell between 1100 and 1450 C.E., after which the area was abandoned until around 1660 C.E. How and why Mississippian chiefdoms rose and fell is poorly understood. Certain stresses such as soil exhaustion, drought, depletion of core resources, military defeat, and contested claims to the chieftainship may have constituted proximate causes for collapse. However, archaeologists generally agree that within a chiefdom, there also were inherent structural instabilities, most likely those associated with chiefly power, authority, and ascension.11 Chiefdoms, then, apparently could not withstand serious and prolonged external or internal stresses.

When a chiefdom fell, other chiefdoms around it did not necessarily fall. Archaeologists are beginning to understand that despite the cycling of chiefdoms, there was an overall regional stability in the Mississippian world. As David J. Hally demonstrates for present-day north Georgia, the chiefdoms in this area were integrated into a regional system of “interaction, interdependence, and the movement of energy, material, and information among polities.” When a chiefdom fell, a regional adjustment followed, as people joined other existing chiefdoms and new areas opened for the settlement and development of new chiefdoms. Ecological parameters also shifted to accommodate the new settlement layout. Hally proposes that the interplay between cycling chiefdoms and extant chiefdoms sponsored a sustained regional stability. 12

The ritual and political gear of the Mississippian people constitutes some of the most important pre-Columbian artwork from the South. Craftspeople used an assortment of stone, clay, mica, copper, shell, feathers, and fabric to fashion a brilliant array of ceremonial items such as headdresses, beads, cups, masks, statues, cave art, ceramic wares, ceremonial weaponry, necklaces and earrings, and figurines. Many of these ritual items are decorated with a specific repertoire of motifs, such as the hand-and-eye motif, the falcon warrior or Birdman, bi-lobed arrows, severed heads, spiders, rattlesnakes, and mythical beings. 13

Archaeologists studying the Mississippi Period recognized long ago that people across the South shared some ideologies because researchers recovered the same sorts of ritual objects throughout the South. They dubbed these objects the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, which came to be known simply as the Southern Cult. Today, however, archaeologists understand the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex to not necessarily portray a unified religion for the Mississippian world but rather a set of basic concepts and principles that were used by various polities. In other words, there probably was not one religion for the whole of the Mississippian world at the time of contact; several religions, deriving from a fundamental set of beliefs and assumptions, likely coexisted.14

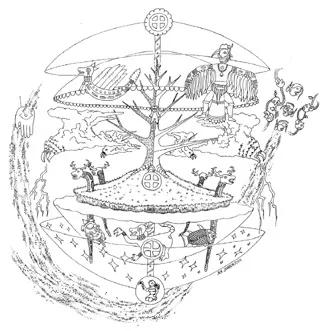

By studying the Mississippian iconography across the Mississippian world in time and space and through careful scrutiny of later documentary evidence, archaeologists and anthropologists have pieced together a plausible

FIGURE 2 Hypothetical model of Mississippian Indians’ conception of the cosmos (From F. Kent Reilly III, “People of Earth, People of Sky,” in Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South, edited by Richard F. Townsend and Robert V. Sharp, 127 [Figure 2]. New Haven, C...