1. Background

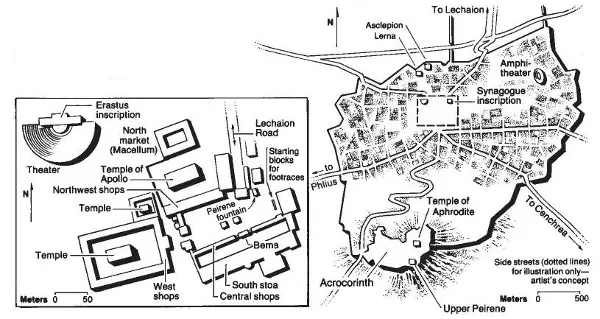

The ancient city of Corinth was located on the isthmus between Attica to the northeast and the Greek Peloponnesus to the south; it had controlling access to two seas—the Aegean to the east and the Ionian to the west. Its eastern port was Cenchrea, located on the Saronic Gulf (Ac 18:18; Ro 16:1), while its western harbor was at Lechaeum on the Corinthian Gulf. This proximity to the seas and its nearness to Athens, only forty-five miles to the northeast, gave Corinth a position of strategic commercial importance and military defense. It lay below the steep north side of the 1,800-foot high fortress rock, the Acrocorinth with its temple of Aphrodite. Thus located, the city received shipping from every major city on the Mediterranean. Instead of going around the south end of the Peloponnesus, ships often docked at the Isthmus and transported their cargoes by land vehicles from one sea to another; or if the ships were small, they were dragged the five miles across the isthmus. Today there is a canal running through the narrowest part of the isthmus near Corinth.

Corinth was a prosperous city. At the peak of its power and influence it probably had a free population of 200,000, plus half a million slaves in its navy and in its many colonies.

Julius Caesar had reestablished Corinth in 46 B.C. He populated it with Roman war veterans and freedmen. In the reign of Augustus (27 B.C. – A.D. 14) and his successors, the city was built on the pattern of a Roman city, with all remaining buildings reclaimed and new ones added in and around the old marketplace (the agora). It became the capital of the Roman province of Achaia (cf. Ac 18:1–2), which included all the Peloponnesus and most of the rest of Greece and Macedonia.

The celebration of the Isthmian games at the temple of Poseidon made a considerable contribution to Hellenic life. This temple was located about seven miles east of Corinth, not far from the eastern end of the isthmus. But with the games came an emphasis on luxury and profligacy, because the sanctuary of Poseidon was given over to the worship of the Corinthian Aphrodite, whose temple on the Acrocorinth was once purported to have had more than 1,000 female prostitutes in the pre-Roman era. The Greek language developed a verb, korinthiazomai, which meant “to live like a Corinthian in the practice of sexual immorality.”

Paul probably came to this important but immoral city in the fall of A.D. 50, after preaching the Gospel to the highly intellectual Athenians. He ministered there a year and a half (Ac 18:11) before he was brought by the Jews into court before the proconsul Gallio (v.12). That these were the dates of Paul’s stay at the city is established by comparing the reference to Gallio with a Gallio, proconsul of Achaia, mentioned on an inscription of the Emperor Claudius at Delphi, dated between January and August, A.D. 52. This Gallio took office on July 1, A.D. 51, and Paul had arrived in Corinth about a year earlier. Shortly after this court appearance, Paul left Corinth for Syria (v.18).

In the Corinthian church were both Jews and Gentiles (see 1Co 1). Some Gentile members had Latin names (e.g., Gaius, Fortunatus, Crispus, Justus, and Achaicus: 1:14; 16:17); so did some Jews (e.g., Aquila and Priscilla, Ac 18:1–4; Crispus, the ruler of the synagogue, v.8). No doubt the greater part of the church was composed of native Greeks (cf. 1Co 1:20–24; 12:2).

The existence of a synagogue in Corinth (Ac 18:4–8) is confirmed by an inscribed lintel block with enough of the words remaining to make out the reading “Synagogue of the Hebrews.” The miserable nature of the inscription, which has no ornamentation, fits the social position of the Jewish people at Corinth with whom Paul was dealing (see 1Co 1:26).

Archaeologists have identified other buildings of the ancient city. An ornamented triumphal gateway, located at the south end of the Lechaeum Road, led into the agora. Around the market were a good many shops, numbers of which had individual wells, suggesting that much wine was made and drunk in the city (cf. Paul’s warning in 1Co 6:10). Located near the center of the marketplace was the bema, the judicial bench or tribunal platform. This was a speakers’ platform, and officials addressed audiences assembled there. It was to this place that the antagonistic Tews brought Paul before Gallio (Ac 18:12–17).

Besides its many temples and shrines, the city had two theaters to the north and west, one of which could seat 18,000 people. In a paved street at the east side of this theater was found a reused paving block with this inscription: “Erastus, the aedile [commissioner of public works], bore the expense of this pavement.” This Erastus may well have been the one who became Paul’s fellow worker (see Ac 19:22; Ro 16:23).

Besides his initial stay in Corinth as recorded in Ac 18, Paul’s contact with the Corinthians can be outlined as follows (see map on Paul’s interaction with the church at Corinth in the introduction to 2 Corinthians): At Ephesus (Ac 19) he apparently wrote the “previous letter” (1Co 5:9—now lost to us). Besides hearing of the Corinthians’ seeming misunderstanding of that letter, Paul had reports from Chloe’s household of disorders in the church there (1:11). He may also have received a delegation from Corinth (16:17) who presented him with questions from the congregation (cf. 7:1). As a result, he wrote 1 Corinthians. Paul then heard other unfavorable reports from the church and paid them a “painful visit” (2Co 2:1). This visit was no doubt necessary because the church had failed to act on Paul’s advice given in 1 Corinthians. Upon his return to Ephesus, he sent the church a “sorrowful letter” (2Co 2:4; 7:8–9), probably carried by Titus. From Ephesus Paul went to Macedonia, where he received from Titus an encouraging report (2Co 7:5–7). So he wrote 2 Corinthians, expressing his gratitude for the improvement. Later he spent the winter in Corinth (Ac 20:2–3) before departing for Jerusalem with the contribution for the poor among the Christians of Palestine. On the basis of this analysis of the events, we may conclude that Paul wrote the Corinthians four letters (two of which have been lost) and that he paid the church three visits.