Chapter 1

Truly great teaching

My first teacher

A garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all it teaches entire trust.

Gertrude Jekyll

When I began my teaching career at Eastbourne Sixth Form College one of my biggest influences was Kate Darwin. We were appointed on the same day but she was nearly twenty years older than me. Kate is a truly great teacher and one of the wisest people I know.

We shared the driving from Brighton to Eastbourne and within the confines of our cars we swapped stories. Kate’s dad had been to Cambridge and won a university prize which her husband-to-be, Chris, was awarded a generation later. Kate’s dad was a head teacher. He died suddenly when Kate was only 18 years old. He had written with the same ink pen for the whole of his life; the story of her dad and his Waterman is best told in a sonnet I wrote for Kate:

His choice of pen remained the same

From undergraduate Cambridge days

To signing his headmaster’s name –

A Waterman in mottled beige.

The cursive blacksmith’s art had honed

The ink-filled gold into a tool

For use by him and him alone –

His hand made them inseparable.

Gold outlasts all. The pen was left

A legacy, bequeathed to her

Whose writing pleased the family most:

But straining through the unknown curves

It snapped, to leave the nib’s new host

Mourning afresh, doubly bereft.

And whilst not educated like Kate’s father, my dad was a teacher in many ways too. Apart from learning how to play golf with him, he taught me a lot about the countryside. He’d grown up four miles from his school and had to walk there and back every day through the Sussex fields. He taught me how to strip a sapling for a bow and arrow, how to predict the weather, how to catch a fish. I can remember as a 6-year-old watching him stalk a trout in an eddied pool on a Sussex stream for nearly an hour before he caught it. He was a study in patient persistence.

I hadn’t realised quite what a teacher he was until my eldest sister, Bev, who knew him that much longer than I did, wrote to me nearly thirty years after he’d died:

After I’d wiped the tears away, one thing that struck me about Bev’s words was the first three things she cites which dad showed us: how to respect the countryside, kindness and honesty. They are the exact same values of our school: respect, honesty and kindness.

Dad tended roses with pure artistry. He died three years from retirement and the chance to lie in his own bed of roses forever. And just as Kate was chosen to receive her dad’s pen, I became the depository for all my dad’s possessions. Mother still sends me odd artefacts she finds, like his National Service discharge documents – he was conscripted into the navy for two years.

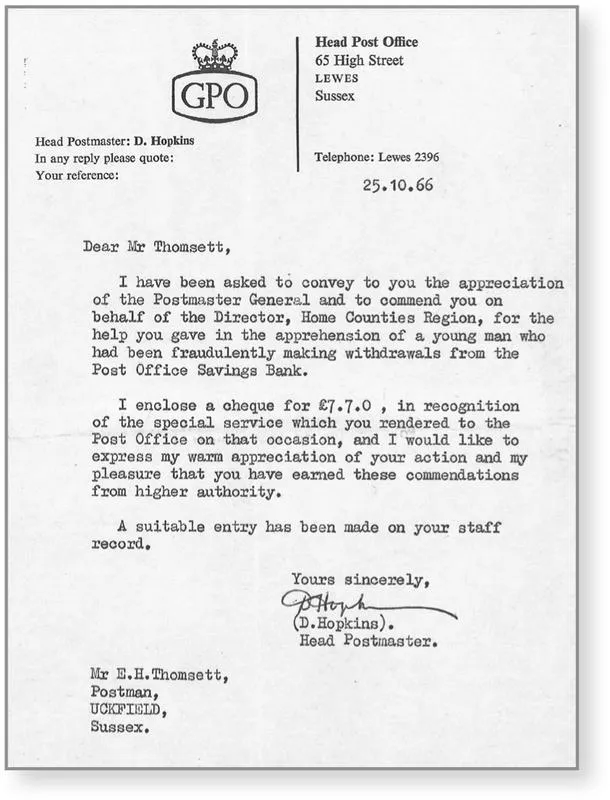

His glasses were a shock when I opened the case; they are half-rimmed ones and the way he used to look over the top of them and grin seemed encased with them. Mother sent me this letter which is now framed on my office wall:

In the event of a fire this is the first thing I would grab. The letter captures perfectly dad’s honesty which Bev had so sharply observed, and I love the way the class system – which pervaded mid-1960s Britain – is clearly evident in the letter’s tone. Worth noting too that in 1966, £7.7.0 was a week’s wages to a postie.

Truly great teaching

The fundamental purpose of school is learning, not teaching.

Richard DuFour

Before we go any further, it’s important to explore the core business of any school: teaching. And it’s worth emphasising that we are trying to focus upon teaching not teachers. Professor Chris Husbands explained beautifully why it is worth making this subtle distinction in a blog post where he pointed out, ‘We can all teach well and we can all teach badly … more generally, we can all teach better: teaching changes and develops. Skills improve. Ideas change. Practice alters. It’s teaching, not teachers.’ This is a helpful distinction because it depersonalises pedagogy so that we can at least begin to talk about improving teaching without being critical of the individual person who is doing the teaching – something which is generally so hard to achieve.

The more I read about teaching, the more difficult it is to define teaching, let alone truly great teaching. If you read Graham Nuthall’s The Hidden Lives of Learners, or Daniel Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School? or Paul Hirst’s ‘What is Teaching?’, you’ll understand why anyone could feel confused about what truly great teaching looks and sounds like.

Hirst says, ‘Successful teaching would seem to be simply teaching which does in fact bring about the desired learning.’ Within that seemingly simple statement lies the complex relationship between teacher and student, something quite delicate but crucial to successful teaching and learning. And when Biesta writes, ‘it is not within the power of the teacher to give this gift [of teaching], but depends on the fragile interplay between the teacher and the student. Teachers can at most try and hope, but they cannot force the gift [of teaching] upon their students,’ what ...